'When the revolution broke out in 2011, Firas al-Ali was playing in Damascus for Al Shorta, and for the Syrian national team. “Society treated me like a superstar,” he told me. “When I went to the shop it would take me four hours to deal with the attention from fans!”

With his previous club – Al-Taliya of Hama – Firas won the Syrian Cup twice and reached the quarter-finals of the Asian Football Confederation Cup (AFC), Asia’s version of the Europa League. Firas is a winger and a free-kick specialist whose left foot would impress Gareth Bale. Al-Taliya’s fans recorded a song for him, which sounds better in Arabic, but goes something like: “When you run on the pitch, the fans boil over, your crosses are so beautiful, Firas al-Aaaaliii!”

As a footballer, Firas witnessed some of the nepotism and corruption of Bashar al-Assad’s dictatorship first-hand – players who were picked because of their connections with the regime rather than their talent. Firas had felt critical of Assad, but he had kept quiet, as did most under the terror of Assad’s mukhabarat, the secret police.

But when the revolution broke out, Firas joined the protests, covering his face to hide his identity. He got into arguments with teammates who had continued to support Assad, even as the dictator’s security forces bore down on peaceful protesters with extreme violence, brutality that soon ensnared his family. His 19-year-old cousin was killed at a protest – the bullet entered his eye and came out of his head. His niece was killed – completely vaporised when a barrel bomb fell directly on her house.

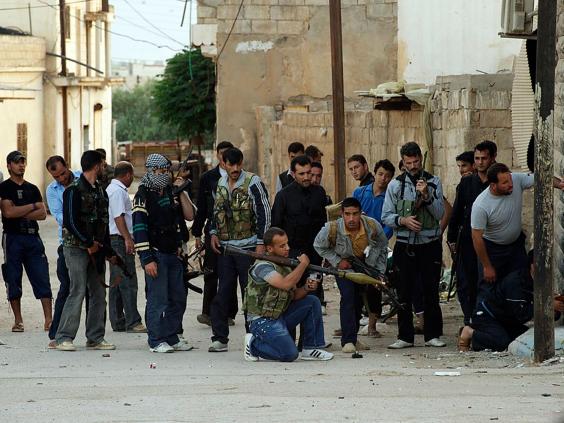

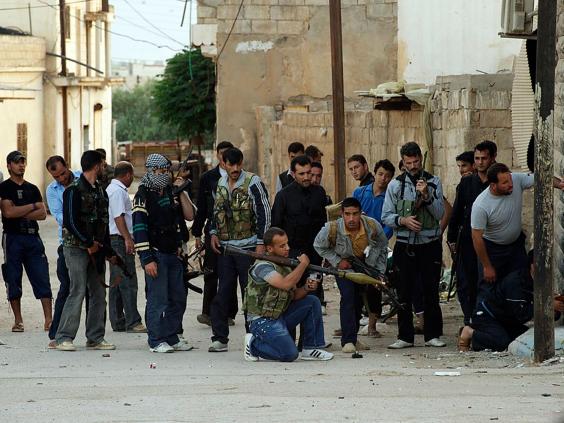

As months went by, the protests continued and the repression intensified, giving way to an increasingly complex, factionalised civil war as the opposition took up arms. Firas’s hometown of Kafr Zeita, near Hama, became associated with the rebel Free Syrian Army (FSA). Despite being a police officer, Firas’s brother was arrested because of his connections to the rebellious town. Meanwhile, Firas remained in Damascus, where he would hear gunfire during training. The stadium was converted into a military base for the regime.

While on a training camp with the national team he watched from the window of his hotel as smoke rose from shelling across Damascus. One day he found out that another of his cousins, just 13, had been killed by the security forces. Half an hour later he joined the rest of the team for dinner – one teammate mocked the protesters and Firas lost it: he had to be pulled off him. Firas couldn’t take it anymore; it was time to defect.

But when the revolution broke out, Firas joined the protests, covering his face to hide his identity. He got into arguments with teammates who had continued to support Assad, even as the dictator’s security forces bore down on peaceful protesters with extreme violence, brutality that soon ensnared his family. His 19-year-old cousin was killed at a protest – the bullet entered his eye and came out of his head. His niece was killed – completely vaporised when a barrel bomb fell directly on her house.

As months went by, the protests continued and the repression intensified, giving way to an increasingly complex, factionalised civil war as the opposition took up arms. Firas’s hometown of Kafr Zeita, near Hama, became associated with the rebel Free Syrian Army (FSA). Despite being a police officer, Firas’s brother was arrested because of his connections to the rebellious town. Meanwhile, Firas remained in Damascus, where he would hear gunfire during training. The stadium was converted into a military base for the regime.

While on a training camp with the national team he watched from the window of his hotel as smoke rose from shelling across Damascus. One day he found out that another of his cousins, just 13, had been killed by the security forces. Half an hour later he joined the rest of the team for dinner – one teammate mocked the protesters and Firas lost it: he had to be pulled off him. Firas couldn’t take it anymore; it was time to defect.

At dawn the next day, he sneaked away from the training camp, from the city, from his career, and set out for Kafr Zeita, some 300 kilometres north of Damascus, but the national team – preparing visas for a tournament in India – had his passport and military service documents. “At every police checkpoint there was a risk that I would be detained and taken for military service,” said Firas. “The thing that saved me was that the soldiers at the checkpoints were football fans – they knew me and I didn’t have to show my ID, otherwise they would have taken me.”

Firas spent around seven months in Kafr Zeita, while the war raged and his money dwindled. “The roof of my house made me a footballer!” Firas told me, while describing his hometown. As a child he’d set up a small table on the roof and would fire endless shots and passes at the target each day, until he could hit it almost every time, and had practically destroyed everything else on the roof in the meantime. When he broke something, his dad would get angry and twist his ear, but the next day would buy him a new football or pair of shoes. Firas played on rough, sandy ground and was forever going through balls and shoes. “My family’s financial situation was not great,” said Firas, “but my father had the feeling that I would become something special.”

Kafr Zeita was subject to heavy bombardment by Assad’s forces. It started with shelling around six times a day. Then the shelling increased and they started to drop bombs from helicopters. It wasn’t safe to hide in the house; they had to flee to nearby farms and fields, returning when the helicopters left. They had a radio that alerted them before an incoming attack, but they had very little time. “If [my brother] didn’t have a car we would have stayed in our house and died,” said Firas.

Firas spent around seven months in Kafr Zeita, while the war raged and his money dwindled. “The roof of my house made me a footballer!” Firas told me, while describing his hometown. As a child he’d set up a small table on the roof and would fire endless shots and passes at the target each day, until he could hit it almost every time, and had practically destroyed everything else on the roof in the meantime. When he broke something, his dad would get angry and twist his ear, but the next day would buy him a new football or pair of shoes. Firas played on rough, sandy ground and was forever going through balls and shoes. “My family’s financial situation was not great,” said Firas, “but my father had the feeling that I would become something special.”

Kafr Zeita was subject to heavy bombardment by Assad’s forces. It started with shelling around six times a day. Then the shelling increased and they started to drop bombs from helicopters. It wasn’t safe to hide in the house; they had to flee to nearby farms and fields, returning when the helicopters left. They had a radio that alerted them before an incoming attack, but they had very little time. “If [my brother] didn’t have a car we would have stayed in our house and died,” said Firas.

Rockets destroyed his family’s houses, life became unliveable, and Firas went from unemployed footballer to refugee, taking his wife and three kids, and his parents, and crossing into Turkey. It was 2013 at the time, and the Turkish government was still maintaining its open-door policy to Syrian refugees.

While his family went to Karkamis refugee camp, Firas wrangled over a contract with the Jordanian Super League team Al-Hussein. He spent a successful season there but being away from his family for a year proved hard and he returned to Turkey to collect them and bring them over to Jordan. While he was in Turkey, the Jordanian government changed the visa requirements for Syrians. Firas and his family were turned away at the airport and returned to the camp. “I surrendered to bad luck,” said Firas.

While his family went to Karkamis refugee camp, Firas wrangled over a contract with the Jordanian Super League team Al-Hussein. He spent a successful season there but being away from his family for a year proved hard and he returned to Turkey to collect them and bring them over to Jordan. While he was in Turkey, the Jordanian government changed the visa requirements for Syrians. Firas and his family were turned away at the airport and returned to the camp. “I surrendered to bad luck,” said Firas.

The days of receiving daily adoration and an annual salary of over $100,000 – a fortune for most people in Syria – seemed unimaginably distant. “I moved from a five-star environment to one with no stars. The camp and being a refugee, how can I talk about it? Everything is difficult, from the simplest thing. Even leaving the camp is difficult.”

There are seven of them in a three-by-three-metre tent, sleeping next to each other on mattresses on the floor. The bathroom is the length of a football pitch away, and feels much further at night. Only when his family sleeps can Firas have some time alone for his thoughts. By the last three or four days of the month, the money they’ve been given by the camp has usually run out.

There are seven of them in a three-by-three-metre tent, sleeping next to each other on mattresses on the floor. The bathroom is the length of a football pitch away, and feels much further at night. Only when his family sleeps can Firas have some time alone for his thoughts. By the last three or four days of the month, the money they’ve been given by the camp has usually run out.

Firas and his immediate family were relatively safe, but when Firas prepared to talk about his arrested brother he sighed and swallowed and looked down at the table. When he looked up again, the blue in his eyes had faded.

Three years after his arrest, they received news. A government officer had leaked 750 photographs of dead prisoners, and Firas’s brother was among them. In the photo, his neck was covered in bandages. “Maybe they cut his throat,” said Firas. All they knew for certain was that he had been killed 45 days after being arrested.

Firas had been fortunate to avoid his brother’s fate. His fame as a footballer had got him through regime checkpoints, but many footballers and other celebrities who spoke out against Assad’s regime became targets. Dozens of players and coaches have been arrested and killed in a war that has claimed hundreds of thousands of lives.

Amid the privations of Firas’s life, football still keeps him going. He runs a football academy in the camp for around 200 kids. The pitch is bare, rocky ground. They have one football and use stones for training cones. “But when I see the kids are happy I forget that I am a professional player with a lost career,” he said with a smile.

Firas is also involved in a struggle to set up an alternative Syrian national team in Turkey that can rival and displace the official Syrian national team run by Assad’s regime and recognised by FIFA. “I can’t fight with a gun, so I will fight with football and the talent that God gave me.” '

Three years after his arrest, they received news. A government officer had leaked 750 photographs of dead prisoners, and Firas’s brother was among them. In the photo, his neck was covered in bandages. “Maybe they cut his throat,” said Firas. All they knew for certain was that he had been killed 45 days after being arrested.

Firas had been fortunate to avoid his brother’s fate. His fame as a footballer had got him through regime checkpoints, but many footballers and other celebrities who spoke out against Assad’s regime became targets. Dozens of players and coaches have been arrested and killed in a war that has claimed hundreds of thousands of lives.

Amid the privations of Firas’s life, football still keeps him going. He runs a football academy in the camp for around 200 kids. The pitch is bare, rocky ground. They have one football and use stones for training cones. “But when I see the kids are happy I forget that I am a professional player with a lost career,” he said with a smile.

Firas is also involved in a struggle to set up an alternative Syrian national team in Turkey that can rival and displace the official Syrian national team run by Assad’s regime and recognised by FIFA. “I can’t fight with a gun, so I will fight with football and the talent that God gave me.” '

No comments:

Post a Comment