'One warm night in July, a young Syrian ventured into the darkness in hopes of escaping what he once called home. He plodded across valleys and fields, atop mountains and walls, all the while carrying his younger brother in his arms. From documenting the horrors of the war to traveling through tenebrous fields as hyenas howled in the distance, this is the story of Firas al-Abdullah.

Firas hails from Douma, a Syrian city in the region of Ghouta, located northeast of the capital. The region has witnessed some of the most inconceivable atrocities throughout the course of the war that has now spanned seven years.

After two rebel offensives that drove out régime forces, the Assad régime, backed by Iran and Hezbollah, counterattacked and laid a siege around Eastern Ghouta in 2013.

Among the besieged cities was Firas’ hometown of Douma. The UN Commission of Inquiry on Syria described the siege as ‘barbaric and medieval’. Numerous war crimes and crimes against humanity were committed during the 5-year long siege, ranging from the use of prohibited weapons to deploying starvation as a method of warfare.

The deadliest single incident against civilians in the area was the chemical attack of August 21, 2013. This attack also constituted the deadliest use of chemical weapons in 25 years.

A UN report confirmed that the attack was carried out using rockets filled with up to 60 litres of the nerve agent sarin. According to a preliminary U.S. government assessment, the attack claimed the lives of over 1,400 people including at least 426 children.

While the UN report failed to assign blame for the attack, several independent sources reported it was executed by the Syrian régime. Peter Bouckaert, a weapons specialist at Human Rights Watch, explained that the rocket systems identified in the UN report are known to be within the arsenal of the Syrian armed forces.

In early 2018, the persistent attacks on Eastern Ghouta intensified. A publication from Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) described the situation as “an outrageous, relentless mass-casualty disaster.”

The report released medical data from facilities that the organisation supports gathered during the first two week period of the military offensive. It revealed that from 18 February to 3 March, an average of 71 people were killed per day.

A UN report confirmed that the attack was carried out using rockets filled with up to 60 litres of the nerve agent sarin. According to a preliminary U.S. government assessment, the attack claimed the lives of over 1,400 people including at least 426 children.

While the UN report failed to assign blame for the attack, several independent sources reported it was executed by the Syrian régime. Peter Bouckaert, a weapons specialist at Human Rights Watch, explained that the rocket systems identified in the UN report are known to be within the arsenal of the Syrian armed forces.

In early 2018, the persistent attacks on Eastern Ghouta intensified. A publication from Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) described the situation as “an outrageous, relentless mass-casualty disaster.”

The report released medical data from facilities that the organisation supports gathered during the first two week period of the military offensive. It revealed that from 18 February to 3 March, an average of 71 people were killed per day.

By the end of March, Douma remained the last rebel enclave in the Eastern Ghouta.

The following month, a barrel bomb carrying sarin was dropped over the city, killing at least 70 people. Medics on the ground reported that the symptoms of those being treated were consistent with that of nerve agent exposure.

The attack was attributed to the Syrian régime by local activists, aid workers, and a number of nations. Russia, a key ally of the régime, claimed no attack took place and that video evidence of it was staged and directed by British intelligence.

The following month, a barrel bomb carrying sarin was dropped over the city, killing at least 70 people. Medics on the ground reported that the symptoms of those being treated were consistent with that of nerve agent exposure.

The attack was attributed to the Syrian régime by local activists, aid workers, and a number of nations. Russia, a key ally of the régime, claimed no attack took place and that video evidence of it was staged and directed by British intelligence.

For all five years of the siege, Firas and his companions would traverse the rubbled streets making video reports of the many massacres committed, which he would then post on his social media accounts.

After a ruthless military campaign, Firas and his family were forcibly displaced to northern Syria as part of an evacuation deal on April 1.

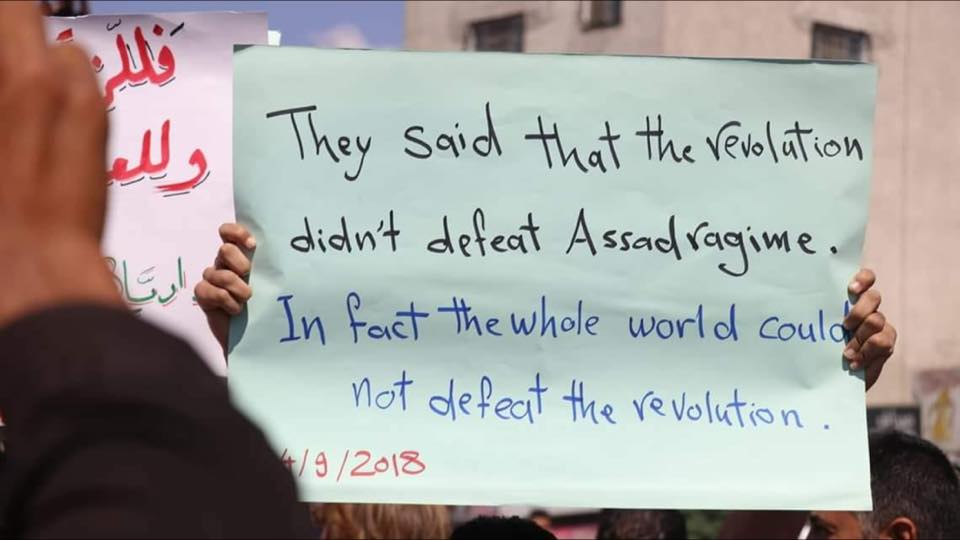

“Life in the north was very difficult. We’d hear of assassinations and kidnappings regularly, especially of activists. So it was very hard for me there.” Consequently, his family made the decision to move to Turkey. He explains, “We wanted to go on with our lives but of course, that doesn’t mean we wanted to forget. One cannot forget the revolution…to do that would be to let down all the people that have been martyred, all the people still detained, everyone.”

After a ruthless military campaign, Firas and his family were forcibly displaced to northern Syria as part of an evacuation deal on April 1.

“Life in the north was very difficult. We’d hear of assassinations and kidnappings regularly, especially of activists. So it was very hard for me there.” Consequently, his family made the decision to move to Turkey. He explains, “We wanted to go on with our lives but of course, that doesn’t mean we wanted to forget. One cannot forget the revolution…to do that would be to let down all the people that have been martyred, all the people still detained, everyone.”

Firas and his family had made a deal with a smuggler to reach Turkey. Their perilous journey had begun late at night on July 21 as they walked through the groves of Deir Sawwan. The sound of hyenas howling loudly did not weaken their resolve. They rested under an olive tree as they waited for the smuggler's signal that the coast was clear.

Later into the night, they finally reached the border wall that was perched on a mountain. Firas, along with his parents and siblings, walked in a straight line on top of the wall, which was a mere 15 centimetres (approximately 6 inches) in width. There was no room to put one foot to the left. The further they walked along this narrow edge, the higher they got off the ground. Firas looked below only to find himself above a 30-metre deep valley.

Firas’ younger brother Muhammed is as old as the war. He had told him before leaving, “you'll be happy in Turkey. You'll be able to leave the house and play in nice, clean streets.” As they continued to tread the edge of the 1km-long wall, Muhammed's foot suddenly slipped off to the left and just as he was about to fall, Firas grabbed his wrist in mid-air.

Among the items in the 20 kg backpack Firas carried were the keys to his house, which was heavily damaged by airstrikes.

Later into the night, they finally reached the border wall that was perched on a mountain. Firas, along with his parents and siblings, walked in a straight line on top of the wall, which was a mere 15 centimetres (approximately 6 inches) in width. There was no room to put one foot to the left. The further they walked along this narrow edge, the higher they got off the ground. Firas looked below only to find himself above a 30-metre deep valley.

Firas’ younger brother Muhammed is as old as the war. He had told him before leaving, “you'll be happy in Turkey. You'll be able to leave the house and play in nice, clean streets.” As they continued to tread the edge of the 1km-long wall, Muhammed's foot suddenly slipped off to the left and just as he was about to fall, Firas grabbed his wrist in mid-air.

Among the items in the 20 kg backpack Firas carried were the keys to his house, which was heavily damaged by airstrikes.

In the early hours of the morning the al-Abdullahs had finally reached the end of the wall, whose construction was not completed. By stepping off its edge, they had taken their first steps on Turkish soil.

Their strenuous journey continued as they walked for another three hours between mountains and through rock valleys. At one point, Firas had to carry Muhammed as he jumped over a river. His mother too grew tired, so he alternated between carrying her and his brother. “It was an extremely tiring course, and it was all so dark. The moonlight wasn't enough,” he says.

After walking over 5 kilometres since stepping off the border wall, they reached the Turkish city of Kilis. Parched and weary, a taxi with whom the smuggler had a deal took them to a flat to rest. Shortly after, another taxi picked them up for a 16-hour drive to Istanbul where their relatives awaited them. They reached Istanbul at 10:30 PM on July 22.

When asked to express his thoughts upon reaching Istanbul, he explained, “I was feeling quite shocked for about a week and in disbelief that I left [Syria] and am now in a place where people live normally. I had reached the ‘real world’ – that’s what I call it – the real world that everyone was living in but we were excluded from on account of the brutal oppression we had to endure under the Syrian régime. [The régime] made us live in a sort of regressive, barbaric age within this larger ‘real world’.”

He expressed his delight at the sight of streetlights for the first time in seven years. “For the first time in years we saw streets undamaged by missiles, sidewalks unmarred by shrapnel, and walls unblemished by war,” he said.

Their strenuous journey continued as they walked for another three hours between mountains and through rock valleys. At one point, Firas had to carry Muhammed as he jumped over a river. His mother too grew tired, so he alternated between carrying her and his brother. “It was an extremely tiring course, and it was all so dark. The moonlight wasn't enough,” he says.

After walking over 5 kilometres since stepping off the border wall, they reached the Turkish city of Kilis. Parched and weary, a taxi with whom the smuggler had a deal took them to a flat to rest. Shortly after, another taxi picked them up for a 16-hour drive to Istanbul where their relatives awaited them. They reached Istanbul at 10:30 PM on July 22.

When asked to express his thoughts upon reaching Istanbul, he explained, “I was feeling quite shocked for about a week and in disbelief that I left [Syria] and am now in a place where people live normally. I had reached the ‘real world’ – that’s what I call it – the real world that everyone was living in but we were excluded from on account of the brutal oppression we had to endure under the Syrian régime. [The régime] made us live in a sort of regressive, barbaric age within this larger ‘real world’.”

He expressed his delight at the sight of streetlights for the first time in seven years. “For the first time in years we saw streets undamaged by missiles, sidewalks unmarred by shrapnel, and walls unblemished by war,” he said.

The terrors Firas experienced in Syria, however, followed him to his new home.

“The second a commercial airplane or helicopter flies over us, we automatically bury our heads between our shoulders and are overcome with fear. It instantly occurs to me to warn the others that the warplanes are above us, as if I was still in Ghouta,” Firas explained. “It may sound crazy,” he chuckled, “but we need some time to forget the horror we lived.”

He concluded, “things are, of course, better here, especially for my family. And my family is all that matters to me.” '

“The second a commercial airplane or helicopter flies over us, we automatically bury our heads between our shoulders and are overcome with fear. It instantly occurs to me to warn the others that the warplanes are above us, as if I was still in Ghouta,” Firas explained. “It may sound crazy,” he chuckled, “but we need some time to forget the horror we lived.”

He concluded, “things are, of course, better here, especially for my family. And my family is all that matters to me.” '