Hadi Abdullah: 'Of course, we all know the ferocity of the military campaign of the al-Assad régime, Iran and Russia against the areas of the Idlib and Hama countryside. Everyone knows that not a day goes by without a massacre, blood in the streets, without that which displaces hundreds of thousands of civilians from their homes.

But there is a thing we don't understand. Why do the areas fall one after the other in the Idlib and Hama countryside? Why?

In this video, we don't address anyone outside Syria, not the UN, the Security Council, or anyone else. We got tired of addressing messages to them for a whole seven years without any result.

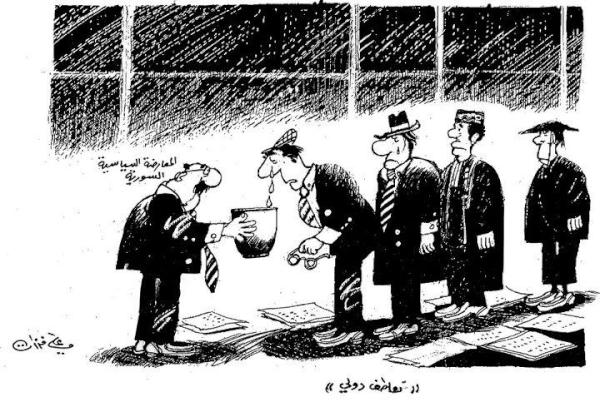

My message is to the leaders of the factions. Leaders of the factions, where are you? Where is the faction that said, we are two-thirds of the military force in Syria? Where are they? Where is the faction that attacked many other factions, for fulfilling the agreements of Astana? The decisions of Astana you fulfil exactly, only there is an increase in the daily bombing of civilian areas.

Good. Put this group aside. Where are the other factions? Where are the leaders of the factions? When was the last time a leader of a faction or military commander appeared in the media, to tell the people what is going on? Is it not the people's right to know what is happening?

Where are the leaders of the factions? If someone is sick, we will visit and take care of them. Seriously, where are they? If someone is sick, we will visit them. If someone has a problem, we will help to solve it. But at least, come out and clarify to the people that one-two-three are happening. It's the people's right to know.

I wish the leaders of the factions would walk in the streets, appear in the media walking the streets, see the refugees sleeping in the streets, sleeping in their cars, those who were expelled from the Idlib and Hama countryside. I wish they would walk in the streets, and listen to those people.

We aren't stupid. If there is an agreement by particular countries to draw the borders, to surrender certain areas, let us know to whom and where. At least come and make it clear to the people, so they will have a bit of time to prepare, check their houses for the last time, leave before the time arrives, remove their property in time, that they have an idea what is happening, that all of us understand this event.

Many journalists and even ordinary people don't talk about this. I don't know why. It is our right to know. For sure, we aren't afraid of anyone. We only fear the Lord of the worlds. It is our right to know what is happening. And we have the right to demand that someone comes and makes clear that one-two-three is happening.

This is not a message of defeat or despair. Never. Because we have everlasting certainty. We are in Syria, and we are not leaving it. The thing that lets us stay in Syria is the certainty in our hearts that they are all transitory - occupiers, Iranians, Russians, the Assad régime along with them, even the factions - and what stays is the people with the Permission of Allah.'

Note 23/7/25, link broken.