'On an autumn afternoon in 2015, Firas Abdullah was relaxing at home as the familiar roar of an aircraft swelled overhead. When a bomb fell nearby and the sound of an explosion reverberated through his neighborhood, he dashed out his front door and weaved through cramped avenues.

But he ran in the opposite direction as everyone else.

Firas was not surprised by what he discovered at the site of the wreckage. Pipes and wood and bricks were strewn everywhere. Avalanches of debris cascaded at varying tempos. Residents searched frantically for loved ones. A corpse lay unattended in the middle of the road.

Firas took a deep breath as he scanned the destruction. A sulfuric odor penetrated his senses. He told himself to shake off the terror, to mute the cacophony of screaming, blazing fire, and wailing sirens. Then, armed with a Nikon D7100, he began documenting everything around him.

A self-taught photographer and filmmaker, Firas has taken it upon himself to chronicle the events unfolding inside Douma, a suburb of Damascus, Syria. His objective is clear: to counteract Bashar al-Assad’s propaganda campaign, which he says justifies these barrages by claiming terrorists, not civilians, are being murdered.

And so he thrust himself into the rubble, at the epicenter of the chaos, risking his life for the perfect shot — the kind that will resonate with people beyond his country’s borders. Eventually, he found it. With a decimated car, rescue workers, and a dead body in the background, he snapped a picture of an olive branch resting next to a pool of fresh blood.

As he took a minute to preview the photo on the screen of his DSLR, another roar crescendoed. It is well-known in Douma that government forces — sometimes Syrian, other times Russian — like to reappear at the scene of their initial attack to kill those who try to help victims.

Firas looked up and saw a jet soar across the sky; as everyone scattered, a missile pierced the haze and struck the earth meters from Firas, and in this moment, as he shut his eyes and a deafening boom rocks the streets, he peacefully accepted he might be meeting his end. Miraculously, he opened his eyes to realize he was more or less unscathed; the remains of a crumbling wall shielded him from the blast, undoubtedly saving his life.

Grateful for such good luck, he rushed home and uploaded JPG files to his computer. As he typed away, Firas acknowledged the war was unlikely to cease in the near future. And he recognized that the region’s most painful chapter could be on the horizon.

Nevertheless, he is steadfast in his belief that fighting disinformation, and recording what revolutionaries have endured since peaceful protests were first met with violence, must continue. “Our cameras are our weapons,” he said, “to show the world what is really going on here.”

Firas was six years old when Syrian ruler Hafez al-Assad, who assumed power after orchestrating an effective coup in 1970, became gravely ill and passed the torch to his son, Bashar. With a London-educated doctor in charge, freedom-seeking individuals in Douma — and millions more around the country — hoped the change in guard would transform Syrian into a modern nation.

The hopes for reform gradually dimmed, but as Firas navigated his way through elementary school, he wasn’t concerned with such matters. He was worried about cartoons, karate, and making his presence felt inside a home that included two parents and four brothers. He became interested in electronics, too, and in fourth grade, his father bought him his first camera:a Sony Cybershot. Through internet tutorials and his own instincts, he figured out how to frame an image, how to approach different lighting and, most importantly, how to “express the imagination” he felt.

As Firas’ hair grew long in the back and thin below his nose and lips, he became a hard-working student who also liked to socialize. Most weekends were spent partying downtown. While at home, programs in Adobe Creative Suite piqued his interest, as did shooting and editing video.

I have so many good memories from the past,” he said. “I miss the Firas I once was. I didn’t know then these were the last normal days in my life.”

Nearly 100 miles north, Miream Salameh was enjoying a life far more progressive than Middle Eastern stereotypes might lead one to expect. Although wide swaths of Syria were and remain conservative, her birthplace, Homs, was then a vibrant, cosmopolitan city — known for its religious diversity and intellectual freedom.

Born into a Christian family, Miream, now 33, never feared judgment for her beliefs, spiritual or otherwise. Instead, curiosity was encouraged: Miream visited Muslim friends at their mosques, and her Muslim friends visited her at a local church. They attended the same classes. They lived in the same neighborhoods. And they believed their different faiths were simply different paths to the same goal.

Growing up in a forward-thinking society allowed Miream to explore her creative side. When she fell in love with painting at a young age, her parents and two brothers, Johny and Suhail, supported her pursuit. She enrolled in art school, where she was introduced to an instructor named Wael Kasstoun, a renowned sculptor and painter.

“He taught me everything about life and art,” Miream recalled of her teacher. “He taught me how to think with my heart. After I knew him, I started to be a different person. I became someone who cares about others, someone who is filled with love and sees the beauty on the inside.”

Wael and Miream began spending most of their free time together, working with canvases and clay from sunrise to sunset. Miream began to see him intermittently as a second father, a third brother, a best friend. Little did Miream know that his lessons would prepare her everything that followed December 17, 2010, when a Tunisian street vendor doused himself with gasoline, lit a match, and changed the course of the Arab world forever.

The outcry in Tunisia was the dawn of what was quickly deemed the Arab Spring. Protests in Egypt led to President Hosni Mubarak’s resignation; dissent in Libya ignited a civil war that led to the death of its despotic prime minister, Muammar Gaddafi. More demonstrations took place in Oman, Yemen, Morocco — and, of course, Syria.

The conflict in Syria began in earnest when thousands in Damascus and Aleppo took to the streets in what marchers called the “Day of Rage.” Firas, then 17 years old, was in awe of the movement — its size, its message, its aspirations.

The first rally in Douma occurred on March 25. Firas chose to participate, and as a crowd assembled, he pulled out his flip phone and recorded hundreds praying in the street. The positive energy was contagious. Confidence was high. Firas had little reason to believe many of these men would be killed in the years ahead.

When Assad refused to back down and the conflict turned into a vicious war, the internet became an important resource for Syrian rebels. Cyberspace made it easy to organize, support one another, and build meaningful relationships. Syrian Facebook users eagerly created groups to chat about the cause and add like-minded people to form inclusive circles. Miream, at this point 28 and a vocal critic of Assad, logged on one day and saw a friend request from a teenager named Firas Abdullah. She immediately clicked confirm.

Once fighting took over Homs, Miream’s large informal network brought her a secret gathering at an abandoned office. There, she and a friend met a second pair of revolutionaries to discuss ways they could do more for the opposition. (Miream never learned the names of the other two; all four used aliases so, if somebody got captured, he or she wouldn’t be able to give up the accomplices while being tortured.)

They decided the best course of action was to found an anti-government magazine. They agreed on a simple name: Justice.

Miream handled the publication’s visuals. She drew caricatures meant to embarrass the regime. She took photographs of the ruin all around her. She reported the names of casualties and gathered clippings of a banned book, which preserved the journal entries of a Syrian incarcerated in one of Assad’s prisons.

More peopled started volunteering for Justice, and to the group’s delight, it gained a sizable readership among fellow dissidents. But popularity came at a cost. Roughly six months after they distributed the first issue, Miream and her colleagues were on their way to meet when they heard Assad’s forces, having caught wind of their operation, raided the office.

They didn’t let this deter them. Focused on maintaining their schedule, they moved to a makeshift bureau in the al-Shamas neighborhood. Later that afternoon, however, gang members affiliated with Shabiha — a militia loyal to Assad — stormed the neighborhood, enclosed the area, and began dragging men out of houses.

What happened next is forever burned into Miream’s memory. The officers rushed civilians into a courtyard and executed a drove of them in front of a throng of onlookers. Bedlam ensued as the shots rang out. One man died as a tank rolled over his body; about 150 more were taken into custody, and the detained women were stripped of their clothes — including their hijabs — and hauled away naked.

As arrests were being made, the magazine staff sprinted away and, to its disbelief, located an exit not manned by combatants.

“We just left everything and ran,” Miream said. “There was no other choice.”

Though Miream eluded trouble in al-Shamas, her problems were only beginning. She learned that her activism landed her name on a government list. Assad’s security apparatus had collected online images of her work and, due to her regular appearances at local rallies, pieced together her identity. Men in uniform began strolling around her neighborhood, asking passersby where she was. Whenever she saw a taxi ramble by, she was afraid an undercover henchman was behind the wheel.

Together, these tactics and anxiety culminated in overwhelming paranoia. “We believed the walls had ears,” she said.

Miream’s unease spiked when she got a vague tip that a man with cruel intentions was coming for her. Then came the direct intimidations. A barrage of strangers called her phone and, on several occasions, asked, “Do you want freedom? We [will] come to your place at night and show you freedom.”

It didn’t stop there. Anonymous Facebook accounts sent her messages filled with rape and death threats; her brother started to get those messages, too, all threatening his big sister.

Nevertheless, Miream wanted to stay in Syria. She wanted to protest, to run the magazine, to paint with Wael. But her parents didn’t share that zeal. Lots of women and girls had already been kidnapped, assaulted, imprisoned and murdered during the war, and her mom was terrified her only daughter would be poached.

The family decided it was time to leave the country. Miream begrudgingly agreed.

“My mom was right,” she said. “If I didn’t leave, I wouldn’t have made it.”

The Salamehs couldn’t bolt simultaneously, though — not without breaking the law. It was prohibited for an entire family to visit a foreign destination, so they decided to abandon their home in three waves: Miream and her brother Johny, her mom, then, finally, her dad and her other brother Suhail.

Less than two years after the winds of the Arab Spring swept through Syria, Miream and Johny packed a few bags, called a licensed taxi, and, without telling anybody, made their way for Lebanon.

Just before Miream and Johny’s departure, the Free Syrian Army (FSA) — a large rebel group directed by officers who defected from Assad’s Syrian Armed Forces — took over most of Douma. Control of the area regularly changed hands in the months, until, in October 2012, the FSA mounted an offensive and earned a decisive win over government troops, ending the back-and-forth.

Against this backdrop, Firas was wrapping up his senior year of high school. Education became his ticket out of the active war zone: Damascus University accepted him into its electrical engineering program.

But as the conflict intensified, Damascus became a dangerous place for him to live. Students’ social media activities were being monitored; thousands of arrests were taking place all over the metropolitan area. Well-aware that his criticisms of the regime could put him in peril, Firas thought he’d be imprisoned if he kept pursing a degree. And, like Miream, he sought to be a part of the revolution.

So Firas dropped out of school in 2013, returned home, and joined the FSA. He ended up on the front lines as the regime attempted to retake Douma. He weathered gun fights, assisted victims of chemical attacks, and, ultimately, helped rebels hold the city.

A year later, in October 2013, Assad’s squadrons closed off most entrances to and exits from Eastern Ghouta, besieging Douma. The rebel soldiers didn’t have to stomach as much close quarters combat, but they had to come to terms with a grimmer reality than they previously tolerated.

Physically closed off from the outside world, Firas’ family — and the rest of the ensnared civilians — wondered how long they could survive in such brutal circumstances. Where would the food come from? What about clean water? Would everyone come together in solidarity or start squabbling under pressure?

The frequency of airstrikes began to escalate. Jets tended to zero in on highly concentrated areas — markets, schools, hospitals. Organizations like Human Rights Watch had trouble delivering aid.

“We had hope it wouldn’t last long,” Firas said about the siege. “We really did.”

Once Miream and Johny exited Homs’ city limits, their cabbie negotiated a course toward Lebanon that led them straight to a checkpoint run by Syrian intelligence. Miream’s heart sank. She knew these policemen often required bribes to let travelers pass through, and she also knew there was a decent chance they would recognize her name. If the men who stopped them rummaged through her stuff, or asked to see her documents, the journey could end in a jail cell.

One of the officers peered into the driver-side window and indeed asked for a bribe. The police ordered the driver to open his trunk and began looking around. With a pit in her stomach, Miream silently prayed and tried not to think about the worst-case scenario. Yet before anyone found her possessions or thought to interrogate her, a cop reached into the pile of items, grabbed some of the driver’s glassware, held the cups to his eyes and remarked how beautiful they were.

Miream was confused by the officer’s interest in such a mundane object but kept silent. For reasons she’ll never understand, the police deemed the glasses sufficient payment and didn’t inquire about her belongings or identification. They were waved through the checkpoint and crossed into Lebanon without any more obstacles.

But, as Miream predicted, that feeling of relief gave way to more apprehension.

In Lebanon, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees didn’t provide them with the support she expected, not even food vouchers. Attempts to cooperate with other UN departments proved to be frustrating and led to dead ends. The Lebanese people weren’t particularly welcoming, either.

Slowly, her family reunited and rented a small apartment. She understood how big of a luxury that home was; lots of Syrians in Lebanon ended up in refugee camps or on the streets. Miream, along with other exiles who had beds to sleep on, dedicated herself to bringing basic resources to those struggling the most. “There was no hope there, in the camps,” she said. “There is no future, and the kids can’t have any childhoods.”

Being away from the revolution drained Miream emotionally. Her mental state only got worse when the gut-wrenching updates started to pour in. One night, she heard two Justice writers were arrested; one died in prison, while other survived his sentence and left for Turkey, then Greece, then Germany. The remaining staff chose to cease operations.

Inconsolable for long spells, Miream grieved death after death, incarceration after incarceration. Then she got the one message she prayed would never come.

Seeking to bolster pro-government propaganda, a member of Assad’s security force paid Wael a visit and asked him to paint an image of a military helmet. Wael refused. Instead, he countered, he’d be willing to draw an image focusing on a drop of blood. This enraged the officer, who scribbled a report in his notebook and stormed out.

Multiple policemen showed up at Wael’s workshop the next day, put him in handcuffs and escorted him to an undisclosed site. Outraged and terrified, his family pleaded for his release. Authorities responded by vowing to let him go the next Sunday, but the weekend passed without news on his whereabouts.

Shortly thereafter, a Homs civilian found a massive pile of dead bodies at a military hospital and identified Wael’s bone-white, emaciated corpse lying near the top. Knowing these carcasses were going to be thrown into a mass grave, the eyewitness discretely retrieved Wael so he could have the burial he deserved.

“It was so hard,” Miream said. “He was everything to me. And I couldn’t go back. I couldn’t go and stand with his wife and kids at his funeral.”

After withstanding unspeakable grief and 12 months in limbo, Miream finally caught a break. The Salamehs had extended family in Australia who knew lawyers capable of getting them out of Lebanon. They applied for visas and, following heaps of paperwork, background checks, and bureaucratic delays, accepted plane tickets to Melbourne.

Miream had yet to fully process her upcoming expedition when she faced grave danger once more.

A week prior to the flight, Miream was at a café with a friend from Syria and an acquaintance when members of Hezbollah, a militant group with considerable power in Lebanon’s government, approached and encircled them with sticks in hand.

The men started telling them they were going to torture them. Miream then saw a suspicious van outside and realized they were targets of a kidnapping attempt. She also realized that, given Hezbollah’s rank in its country, no one, not even the police, was going to protect them. She panicked as the culprit grabbed them and began slashing his stick into their arms, legs, and backs.

Miream steeled herself to be lugged away right as the assailant grabbing her was hit from behind and lost his grip. She glanced up; three men, all Syrian, had rushed over to fight off the would-be abductors. Fists flew. Insults were hurled. Miream, kneeling by the table in a daze, remembers the attackers retreating to their van.

Another close call, another escape.

A storm brewed inside Miream as the trip to Australia neared. She felt sorrow when she thought about the home she may never see again, and the friends she was going to leave behind. She felt relief when she thought about how lucky she was to get away.

“I can’t tell you that feeling, when you are happy but at the same time you are not,” Miream said. “Like, you will be comfortable and everything will be OK with you, and you will be safe, and all these things, but you don’t want to go so far from your land. Because when I fled from Syria, it wasn’t a choice that I wanted. I was forced. They forced me. It was a very difficult time.”

Soon enough, the Salamehs were gliding over the Indian Ocean.

As months passed by and the siege on Douma continued unabated, Firas grew disenchanted with the FSA. He felt like a pawn, and he detested how some politically-charged factions were poisoning the rebel cause. In 2014, he ended his service and returned to reporting, which he considered a more “pure” endeavor.

The life of an independent war journalist suited him well. Firas was brave enough to dart into mayhem, he was motivated to cover Douma relentlessly, and his technical skills improved. He cataloged fatal attacks, schoolboys embracing in front of wreckage, and the Syria Civil Defense — also known as the White Helmets — saving citizens enveloped by chunks of concrete.

One of Firas’ most harrowing days as a reporter occurred on a quiet summer morning that was interrupted by an airstrike. He was already holding his camera when the blast vibrated through his home in Douma, and he was one of the first people to arrive at the scene.

When Firas got there, he noticed an old man sitting in the back of an ambulance holding two little kids, their faces and arms caked in dust. The man, perhaps corralling his son and daughter, is gazing into the distance, his face brimming with anguish, his eyes suggesting a hint of disbelief.

While the boy peers to his right, the girl stares directly into Firas’ lens as the shutter closes. Her frightened eyes meet those of the observer.

“The children, they were so shocked they didn’t cry,” Firas said. “I took this photo for them. It was a normal attack, because the blame went out to the whole world. The girl’s eyes [cast] blame on us all.”

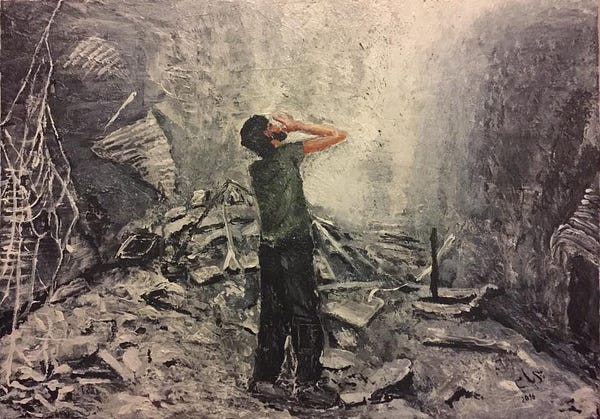

Thousands of Syrians shared the photo online. Miream was settling into her home in Melbourne when she saw the image on Facebook. She found it captivating — so much so that she decided to paint it.

Like the original, her painting of Firas’ picture received acclaim on the internet. As praise flowed in, the two struck up conversation, bonded over all they had in common, and developed an online friendship.

“His photos are so powerful but so sad at the same time,” Miream said of Firas’ work. “It’s very hard sometimes to look at them. I just cried, even when I painted that one, I cried. It was very hard to look at the eyes.”

Firas respects Miream just as much.

“Miream, she is fantastic,” Firas said. “She has a very big heart.”

Together, their creative gifts and social media acumen have started to be noticed. Large news outlets like the Associated Press, Al Jazeera, and Middle East Eye have published Firas’ photographs. When an airstrike killed more than 20 people in August 2015, the AP’s website created an entire gallery of the images he captured from the fallout. American papers, including the Seattle Times and Salt Lake Tribune, used those pictures in their coverage.

Miream’s paintings and sculptures, meanwhile, have been featured at galleries in Melbourne, Sydney, and Victoria. She’s also gone back to her activist roots as a critic of Australia’s draconian refugee policy. “The paintings really do raise awareness,” she said. “People come to me and ask me a lot of questions. ‘What is the meaning of this painting? We need to know more.’ They share in what happened in Syrian when they hear an explanation. They’re trying to speak loudly about our suffering from my art.

“Ever if I don’t speak their language, or if they don’t speak my language, it’s something everyone can understand and feel.”

Over the course of many interviews, Firas and Miream emphasized how their work is making an appreciable impact. And it is: By spreading images all over the globe — online, on walls, on aluminum armatures — they give pause to those who might not otherwise understand the Syrian tragedy. Photos and paintings and sculptures can evoke strong emotions from people young and old. Their goal, now, is to channel those feelings into action.

“I’m trying,” Miream said. “I’m trying to say a message to the whole world, to affect the people deeply, to do something together as humans. If every one of us raises the voices of the Syrian people and talks about their suffering and does a simple action, very simple, tiny action, if all of us think this way, things could be changed.”

Firas and Miream’s desire to reshape Syrian will not fade. However, both vocalized a sense of despair when discussing their country’s short-term outlook. Neither has known a Syria ruled by someone outside the strong-armed Assad family; each understands how dominant the government is, and how little the international community has tried to mitigate what is now the worst humanitarian crisis since World War II.

So while their faith in the a better future is high, the two virtual friends — one more than 8,000 miles from home, the other trapped in a precarious state — know the limitations of their power.

“It is the hardest thing, the most difficult thing that we feel,” Miream said. “We feel totally helpless. We get angry, we want to help, but we can’t do anything. Can I say the truth? I would like to go back and live in the same situation that Firas is in. Because while I live here safe, and I feel my family is safe…” Her voice trailed off and she began to cry.

“I’m sorry. I don’t know what to say. We can’t do anything.”

I asked her if she believes she’ll return to Syria and meet Firas in person.

“I always dream of it,” she said. “We need to go back and all build our country together. We only have this hope. We only have these things to think about. I always want to go back with the people who are still there. They are heroes, you know?”

“There must be a solution to stop the violence against civilians so she can come back,” Firas said. “There should be pressure on the West to find a political solution to fix this war. The solution is not with weapons or with bombs.”

The excitement in Firas’ tone is palpable when he talks about his impact abroad. Knowing outsiders appreciate his reporting lends credence to the idea that he can become a professional, full-time journalist, which is now his career goal.

He doesn’t let himself get too thrilled about that notion, though, for one’s spirits can only get so high in Douma. Especially with the way the war is shaping up in 2017.

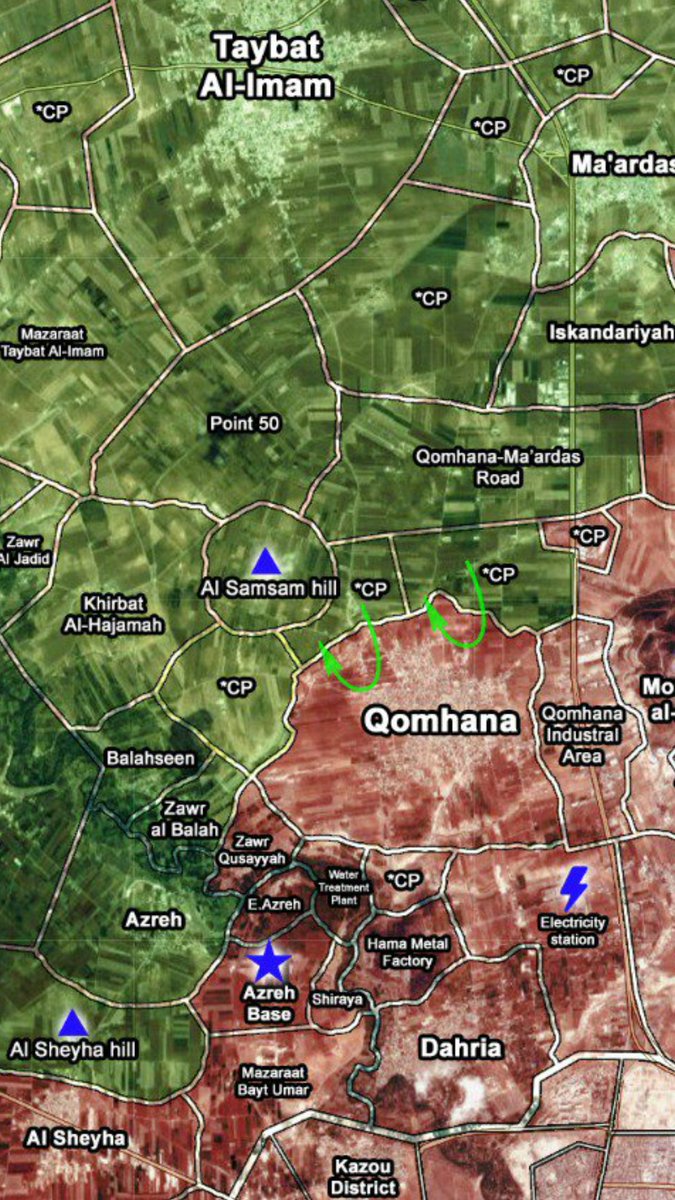

Per a December report from Al Jazeera, analysts say Assad’s regime is “planning an operation to either remove or disarm rebel fighters” in Eastern Ghouta. Because Douma is the largest rebel-held area left in the Damascus suburbs, it could be the location of Syria’s next big fight.

“We actually expect that,” Firas said. “This one will be bigger than before. We all understand it and we’re trying to get ready.”

He clarified that “get ready” means “prepare for the worst,” not take up arms. If this anticipated clash takes place, the rebels will defend themselves, but as morale plummets to lower depths with each passing day, it seems those as if they are resigned to an unfortunate end.

“For people here, death is like anything else. We lost the fear of death. Most people here have this feeling, unfortunately,” Firas said. “You cannot imagine what I am feeling about death. I’m not afraid. Death is usually here for us.”

Though Firas remains upbeat, the war has taken a considerable toll on his psyche. No longer does he get his hopes up when peace talks commence in Geneva. No longer does he anticipate ceasefires will last. No longer does he expect foreign leaders to step in to rescue his family.

And while he’ll try to report indefinitely, no longer does he have illusions about the misery Douma could soon face. “What can we do if the regime comes for us? Nothing that we can do. It’s like waiting for something to pick us up to heaven, to the sky,” he said.

“But I will keep taking photos. Always. The world must know what is happening here. I feel very proud, because I have succeeded in getting part of the reality of my life to the world. It will help to show these pictures of the revolution because they embarrass the system in front of the international courts.

“Someday, [my pictures] will be the images that show why we deserved justice and freedom. Because the camera is more dangerous than lead and iron, and our people will always be stronger than our rulers.” '