'On a cool February afternoon, one of Syria's greatest soccer players sits outside a mall on the Persian Gulf, paralyzed by a decision that he fears could kill him.

For five years, Firas al-Khatib has boycotted the Syrian national team to protest dictator Bashar al-Assad, who bombed and starved Khatib's hometown.

Now, suddenly, Khatib seems to be having a change of heart. He is thinking about rejoining Syria for its final push to qualify for next year's World Cup. His reasons are complicated, and he's reluctant to express them.

"I'm afraid, I'm afraid," he says in stilted English. "In Syria now, if you talk, somebody will kill you -- for what you talk, for what you think. Not for what you do. They will kill you for what you think."

Khatib is bearded and runty, with curly brown hair and kind eyes. He has earned millions playing professionally in Kuwait. The mall's posh setting offers a glimpse into his comfortable life here -- yachts bobbing on scalloped blue water, robed men and women drawing flavored tobacco from tableside water pipes. But Khatib seems nearly crushed by the weight of his dilemma, which he discusses over two days of interviews. "Every day before I sleep, maybe one hour, two hours, just thinking about this decision."

Khatib pulls out his phone to show his Facebook page, which receives a hundred messages a day. Even some of his closest friends are ready to turn on him. One player he grew up with, Nihad Saadeddine, says if Khatib returns to Syria he'll be relegated to "the garbage bin of history along with everyone who supports the criminal Bashar al-Assad." Saadeddine vows never to speak to Khatib again.

Sometime within the next 36 days, when Syria plays its next match, Khatib must choose between two great evils that plague the modern world.

If he rejoins Syria, he will be team captain and the most important player in his country's quest to make the World Cup for the first time. He will also represent a government that -- along with nerve gas, torture, rape, starvation and the bombing of civilians -- has used soccer as a weapon to promote its murderous rule.

If he continues his boycott, he'll be aligned with a complicated movement that began with peaceful demonstrations and has since splintered to include al-Qaida and ISIS. ISIS has used soccer as a backdrop for some of its most heinous crimes, including the 2015 bombings at the Stade de France and a 2016 bombing at a youth soccer match in Iraq that killed 29 children.

"Now, in Syria, many killers, not just one or two," Khatib says. "And I hate all of them."

He's at a loss.

"Whatever happen, 12 million Syrians will love me," he says. "Other 12 million will want to kill me."

If he rejoins Syria, he will be team captain and the most important player in his country's quest to make the World Cup for the first time. He will also represent a government that -- along with nerve gas, torture, rape, starvation and the bombing of civilians -- has used soccer as a weapon to promote its murderous rule.

If he continues his boycott, he'll be aligned with a complicated movement that began with peaceful demonstrations and has since splintered to include al-Qaida and ISIS. ISIS has used soccer as a backdrop for some of its most heinous crimes, including the 2015 bombings at the Stade de France and a 2016 bombing at a youth soccer match in Iraq that killed 29 children.

"Now, in Syria, many killers, not just one or two," Khatib says. "And I hate all of them."

He's at a loss.

"Whatever happen, 12 million Syrians will love me," he says. "Other 12 million will want to kill me."

FIFA has essentially adopted the position of the Assad regime, which maintains that Syria's national team is politically neutral. Dabbas, the Syrian businessman who serves as head of the delegation, says the team's primary goal, beyond qualifying for the World Cup, is "to bring all Syrians together" and "prove to the world that Syria is fine, that Syria has a pulse." The team represents "all of Syria."

But Dabbas makes it clear that Syria is playing for "our president" and is loyal to Assad. "Any Syrian inside Syria represents President Bashar Assad, and His Excellency President Dr. Bashar Assad represents us. We are proud of our president. We are proud of what he's achieved. And we want to send him our regards and thanks for what he has done for Syria, and we are behind him and under his leadership."

Assad, according to Dabbas, watches every game and is "following the most minute details of the team."

But Dabbas makes it clear that Syria is playing for "our president" and is loyal to Assad. "Any Syrian inside Syria represents President Bashar Assad, and His Excellency President Dr. Bashar Assad represents us. We are proud of our president. We are proud of what he's achieved. And we want to send him our regards and thanks for what he has done for Syria, and we are behind him and under his leadership."

Assad, according to Dabbas, watches every game and is "following the most minute details of the team."

There are numerous signs, in fact, that the Syrian national team represents not a unified vision of Syria but the benign face of a ruthless dictatorship. In November 2015 in Singapore, the head coach, a player and the team spokesman showed up to a prematch news conference wearing T-shirts bearing Assad's photo. In comments widely circulated among Syrian refugees, the coach, Fajer Ebrahim, used the World Cup platform to proclaim Assad the "best man in the world."

Ebrahim, who is not coaching the team in the third round of World Cup qualifying, began an interview with ESPN in Kuala Lumpur by launching into an impromptu speech in praise of Assad. "We know our president is the right man, and a very, very great man," he said. "Without our president, Syria is destroyed."

Asked about the appropriateness of using World Cup competition to make political statements, Ebrahim replied: "Everything is linked now. Everything's related."

Given the pressures inside Syria, where thousands of people have been tortured and killed for opposing Assad, it's difficult to assess the candor of those affiliated with the team and what their allegiances are. Anas Ammo, the well-connected former sports writer who has documented human rights crimes against Syrian athletes, works as a sports agent in Mersin, Turkey. He says some players on the national team have family members who were detained or killed by the regime. "They are basically forced to play, otherwise they may kill their relatives," says Ammo, requesting that the players' names remain private to protect them and their families. Ammo says he knows of two national team members who play out of fear that the government, which controls their travel documents, will withhold their passports, making it impossible for them to play abroad. Other players, Ammo says, are loyal to Assad.

Ammo believes that if players were granted control over their passports, a large number would defect.

Ebrahim, who is not coaching the team in the third round of World Cup qualifying, began an interview with ESPN in Kuala Lumpur by launching into an impromptu speech in praise of Assad. "We know our president is the right man, and a very, very great man," he said. "Without our president, Syria is destroyed."

Asked about the appropriateness of using World Cup competition to make political statements, Ebrahim replied: "Everything is linked now. Everything's related."

Given the pressures inside Syria, where thousands of people have been tortured and killed for opposing Assad, it's difficult to assess the candor of those affiliated with the team and what their allegiances are. Anas Ammo, the well-connected former sports writer who has documented human rights crimes against Syrian athletes, works as a sports agent in Mersin, Turkey. He says some players on the national team have family members who were detained or killed by the regime. "They are basically forced to play, otherwise they may kill their relatives," says Ammo, requesting that the players' names remain private to protect them and their families. Ammo says he knows of two national team members who play out of fear that the government, which controls their travel documents, will withhold their passports, making it impossible for them to play abroad. Other players, Ammo says, are loyal to Assad.

Ammo believes that if players were granted control over their passports, a large number would defect.

On the other side of the world is an alternate reality.

One freezing, rainy afternoon in February, two dozen Syrian refugees cram into the visitors locker room of SV Buchholz, an amateur sports club that plays on a lower rung of German soccer called the Bezirksliga. The one-story building, narrow and gray, is tucked into a residential side street in northeast Berlin. Behind it is the soccer field. One by one, the Syrians fish their green jerseys out of a rumpled paper bag. Syria's revolutionary flag -- three red stars superimposed over green, white and black horizontal bands -- is taped over the window.

At least two of these "Free Syria" teams have competed in exhibition matches in Turkey and Germany. The teams, which include veterans of the Syrian Premier League, are part of a Syrian refugee population that has swelled to nearly 6 million -- roughly the population of Massachusetts. The team in Germany represents "the people who have been oppressed by the regime," including "martyred athletes who gave their lives for the country," says the coach, Nihad Saadeddine. "This team, God willing, will be the official representative of Free Syria."

The players from SV Buchholz arrive one by one, nonchalant and carefree. Electronic music pulsates from their locker room, making it feel as if the entire building has a heartbeat. They are mostly blond and fit, as if they emerged from a German travel brochure. The Syrians, even in their new uniforms, seem disheveled and broken, a collection of game individuals who have come together for a cause. "The players who are here, there are a large number who were injured or detained," Saadeddine says. The coach is 35 but looks 10 years older, with thinning dark hair and haunted eyes. A longtime midfielder in Syria, he can no longer play. During the government's siege of Homs, Saadeddine says he was shot in the knee by a sniper, then essentially crushed when a mortar struck behind a wall as he was evacuating women and children from an apartment building. When he arrived in Austria, where he lives now, doctors discovered five cracked vertebrae.

Saadeddine gives his locker room pep talk: "Guys, we have a cause, and I hope everyone will be up to the task -- to demonstrate to people the criminality of this regime, what they have done to athletes and the detainees; It's our obligation to talk about them. ... We need to have our voices heard, that we stand together to expose this regime to the world, that there is a revolution and that there are free athletes. When you say you are on the team of Free Syria, you are representing millions."

One freezing, rainy afternoon in February, two dozen Syrian refugees cram into the visitors locker room of SV Buchholz, an amateur sports club that plays on a lower rung of German soccer called the Bezirksliga. The one-story building, narrow and gray, is tucked into a residential side street in northeast Berlin. Behind it is the soccer field. One by one, the Syrians fish their green jerseys out of a rumpled paper bag. Syria's revolutionary flag -- three red stars superimposed over green, white and black horizontal bands -- is taped over the window.

At least two of these "Free Syria" teams have competed in exhibition matches in Turkey and Germany. The teams, which include veterans of the Syrian Premier League, are part of a Syrian refugee population that has swelled to nearly 6 million -- roughly the population of Massachusetts. The team in Germany represents "the people who have been oppressed by the regime," including "martyred athletes who gave their lives for the country," says the coach, Nihad Saadeddine. "This team, God willing, will be the official representative of Free Syria."

The players from SV Buchholz arrive one by one, nonchalant and carefree. Electronic music pulsates from their locker room, making it feel as if the entire building has a heartbeat. They are mostly blond and fit, as if they emerged from a German travel brochure. The Syrians, even in their new uniforms, seem disheveled and broken, a collection of game individuals who have come together for a cause. "The players who are here, there are a large number who were injured or detained," Saadeddine says. The coach is 35 but looks 10 years older, with thinning dark hair and haunted eyes. A longtime midfielder in Syria, he can no longer play. During the government's siege of Homs, Saadeddine says he was shot in the knee by a sniper, then essentially crushed when a mortar struck behind a wall as he was evacuating women and children from an apartment building. When he arrived in Austria, where he lives now, doctors discovered five cracked vertebrae.

Saadeddine gives his locker room pep talk: "Guys, we have a cause, and I hope everyone will be up to the task -- to demonstrate to people the criminality of this regime, what they have done to athletes and the detainees; It's our obligation to talk about them. ... We need to have our voices heard, that we stand together to expose this regime to the world, that there is a revolution and that there are free athletes. When you say you are on the team of Free Syria, you are representing millions."

One of the Free Syria players, Jaber al-Kurdi, was detained by the regime in 2013 in the city of Hama, where he played for a team called Taliya. Kurdi says he supported the opposition but never fired a gun. "Do you think these hands could carry a weapon?" he says, turning up pink palms. "A girl's hand is bigger than mine." Kurdi says he attended protests and provided clothing and shelter for the displaced: "I don't like blood or bloodshed, but when I saw people arriving in Hama and sleeping outside in the parks and streets, I couldn't just stand and watch."

Human Rights Watch has described Assad's vast prison network as "a torture archipelago." Kurdi says he was held for nine months without trial, shuttled between detention centers in Hama, Homs and Damascus. At the "Palestine" branch of the Military Intelligence Directorate in Damascus, guards repeatedly beat the soles of his feet with a rubber hose and shocked him through electric wires attached to his skull. For a week, he says, he was confined in a narrow ceramic pen, unable to sit and barely able to move. "It's cold, and they would come in and throw water on me and leave," Kurdi says. He says he was let out for five minutes a day to relieve himself and that he occasionally received pieces of stale bread pushed through the door.

Human Rights Watch has described Assad's vast prison network as "a torture archipelago." Kurdi says he was held for nine months without trial, shuttled between detention centers in Hama, Homs and Damascus. At the "Palestine" branch of the Military Intelligence Directorate in Damascus, guards repeatedly beat the soles of his feet with a rubber hose and shocked him through electric wires attached to his skull. For a week, he says, he was confined in a narrow ceramic pen, unable to sit and barely able to move. "It's cold, and they would come in and throw water on me and leave," Kurdi says. He says he was let out for five minutes a day to relieve himself and that he occasionally received pieces of stale bread pushed through the door.

The 25-year-old has soft features, a three-day beard and dark shadows beneath his eyes. At the end of his incarceration, he says, he was brought before a military judge, who ordered him released. As the guard handed him his belongings -- an empty wallet -- he grabbed Kurdi's hand and sliced his index finger with a knife.

"That's so you'll remember us," the guard told him, says Kurdi, holding up a thin scar.

Since arriving in Germany, Kurdi says he's been treated for recurring nightmares in which he sees Syrian security agents chasing him through the bombed-out streets of Hama.

"My heart aches, I swear to God," he says, breaking down during an interview. "I'm not happy here. The German government took us in and gave us safety and security. We appreciate that, but psychologically, we're not happy. Our people are being slaughtered."

Another Free Syria player, Basel Hawa, says he was caught plotting his defection from the Syrian army after concluding: "We're killing our own people." He says he was held for two months in a small cell with 12 detainees who had to defecate in a hole in the floor. Hawa says he was released after Assad granted a limited amnesty in 2014. He eventually fled to Germany.

One player comes up in nearly every conversation with the Free Syria team, but he is not here in Berlin. Jihad Qassab was a retired midfielder in his early 40s who starred for Karama, the professional team in Homs. Why Qassab was arrested, on Aug. 19, 2014, is not clear. There's never been a trial.

Qassab's family and friends believe he was taken to Sednaya Military Prison, the heart of darkness of Assad's torture archipelago. One former detainee told Amnesty International that guards segregate weaker prisoners and force larger ones to rape them. There were constant beatings with pipes, shredded tank treads and hooked cables designed to tear away flesh. Sednaya contains an underground execution chamber consisting of two platforms and dozens of nooses, according to Amnesty International, which called Sednaya "a human slaughterhouse." Amnesty estimates that up to 13,000 Syrians were subjected to a policy of "extermination" over a four-year period at the prison.

Last September, more than two years after Qassab disappeared, it was announced that he was dead. The mosques in Homs were the first to report the news, then social media, the Syrian Network for Human Rights and news wires around the world. There were no other details.

"If Jihad lived in another country, he would have been honored and rewarded for his long history of achievements in sports," says Mohamed Hameed, a former Karama player and a close friend of Qassab's. "In Syria, under Assad, he gets detained and tortured."

Qassab's body was never recovered, according to his friends, and some are convinced he might be alive. Rashad Shamma, an old friend, held a small ceremony for Qassab in front of his candy shop in Saudi Arabia.

It's a measure of Syria's twisted reality that a star like Qassab can disappear, be pronounced dead and have a service held for him yet Shamma can still say matter-of-factly: "He might be dead or alive. Who knows?"

Fadi Dabbas, the vice president of the Syrian Football Association, first told ESPN that he knew nothing about Qassab's fate and had never heard of him: "I do not know of this name at all," Dabbas said. When it was pointed out that Qassab played in the Syrian Premier League for over a decade, he said: "I don't know where he went after he left Karama. I don't know what happened. I have no information about this subject."

One player comes up in nearly every conversation with the Free Syria team, but he is not here in Berlin. Jihad Qassab was a retired midfielder in his early 40s who starred for Karama, the professional team in Homs. Why Qassab was arrested, on Aug. 19, 2014, is not clear. There's never been a trial.

Qassab's family and friends believe he was taken to Sednaya Military Prison, the heart of darkness of Assad's torture archipelago. One former detainee told Amnesty International that guards segregate weaker prisoners and force larger ones to rape them. There were constant beatings with pipes, shredded tank treads and hooked cables designed to tear away flesh. Sednaya contains an underground execution chamber consisting of two platforms and dozens of nooses, according to Amnesty International, which called Sednaya "a human slaughterhouse." Amnesty estimates that up to 13,000 Syrians were subjected to a policy of "extermination" over a four-year period at the prison.

Last September, more than two years after Qassab disappeared, it was announced that he was dead. The mosques in Homs were the first to report the news, then social media, the Syrian Network for Human Rights and news wires around the world. There were no other details.

"If Jihad lived in another country, he would have been honored and rewarded for his long history of achievements in sports," says Mohamed Hameed, a former Karama player and a close friend of Qassab's. "In Syria, under Assad, he gets detained and tortured."

Qassab's body was never recovered, according to his friends, and some are convinced he might be alive. Rashad Shamma, an old friend, held a small ceremony for Qassab in front of his candy shop in Saudi Arabia.

It's a measure of Syria's twisted reality that a star like Qassab can disappear, be pronounced dead and have a service held for him yet Shamma can still say matter-of-factly: "He might be dead or alive. Who knows?"

Fadi Dabbas, the vice president of the Syrian Football Association, first told ESPN that he knew nothing about Qassab's fate and had never heard of him: "I do not know of this name at all," Dabbas said. When it was pointed out that Qassab played in the Syrian Premier League for over a decade, he said: "I don't know where he went after he left Karama. I don't know what happened. I have no information about this subject."

Despite the symbolism, Free Syria's match against SV Buchholz ends in a 5-2 defeat for the Syrians, under a cold and steady rain, in front of a few dozen Germans who straggle in on a Sunday afternoon to watch their friends and relatives play a curious exhibition.

Given the circumstances, the match is both heroic and uncomfortable to watch. The Syrians score first on a beautiful cross. But by the second half, the Germans -- better conditioned and blessed with normal lives that allow them to practice regularly (the Syrians came together for the first time the day before) -- blast away at the goal. One hard shot hits a Syrian defender square in the face, leaving him motionless on the ground for several minutes before he walks off gingerly.

The Free Syrians present themselves as an alternative to the national team sponsored by Assad. But more than anything, the exhibition against SV Buchholz shows that it isn't that -- not even close. There is only one Team Syria, and the players who are good enough to make it must decide for themselves what it represents.

Given the circumstances, the match is both heroic and uncomfortable to watch. The Syrians score first on a beautiful cross. But by the second half, the Germans -- better conditioned and blessed with normal lives that allow them to practice regularly (the Syrians came together for the first time the day before) -- blast away at the goal. One hard shot hits a Syrian defender square in the face, leaving him motionless on the ground for several minutes before he walks off gingerly.

The Free Syrians present themselves as an alternative to the national team sponsored by Assad. But more than anything, the exhibition against SV Buchholz shows that it isn't that -- not even close. There is only one Team Syria, and the players who are good enough to make it must decide for themselves what it represents.

In July 2012, when Firas al-Khatib announced he would no longer play for Syria, his hometown, Homs, was in flames. The west-central city, once Syria's third largest, is known as the "capital of the revolution." The previous year, when peaceful protests against Assad's authoritarian government spread across the country, thousands of Homs residents took to the streets. As he did in other cities, Assad responded with overwhelming force. The government's response to the nationwide protests triggered a civil war that now features a bizarre cauldron of global superpowers, foreign terrorists, warlords, militias and freedom fighters.

Assad's scorched-earth campaign in Homs included rape and starvation -- some residents ate grass to survive, according to witnesses and opposition activists. Massacres were reported in which witnesses saw Assad forces round up and kill civilians.

Khatib is one of Homs' most prominent citizens and one of Syria's most famous athletes -- a national star since his teens. He left the country in the early 2000s to play professionally in Belgium, China and, for more than a decade, Kuwait, where he broke the league's career scoring record. Khatib used his soccer earnings to help build a street in Homs -- Al Khatib Street -- complete with a soccer field and a mosque that also bears the family name. Despite the millions he earned playing abroad, he always came home to represent Syria. "To play for national team, it's 24 million watch you, 24 million support you to win," he says.

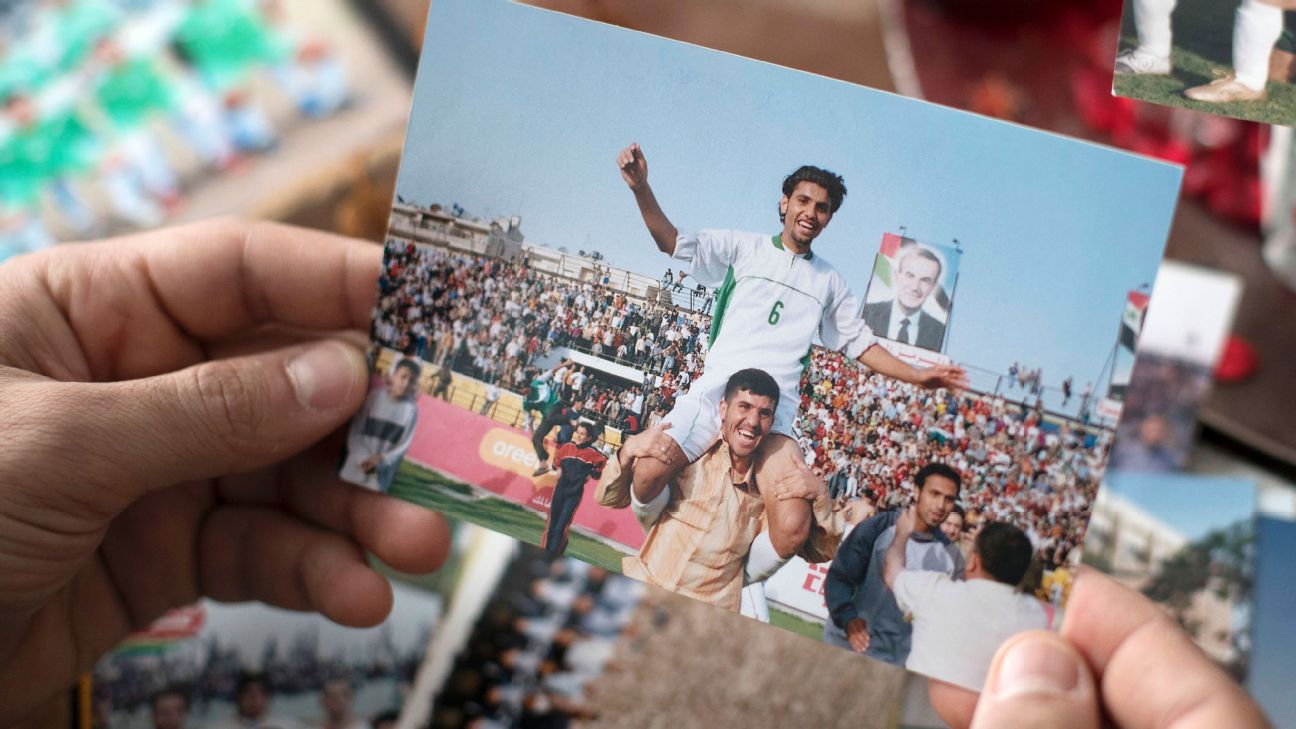

Khatib's boycott, announced at a rally in Kuwait City, was a blow to Assad. Draped in a sash with the revolution colors, Khatib told the screaming crowd: "Here in front of the media, I want to say that I will never play for the Syrian national team as long as there are bombs falling anywhere in Syria."

One man lifted Khatib onto his shoulders. The crowd addressed him as Abu Hamza, an affectionate nickname meaning "Father of Hamza," his oldest son.

"God bless you, Abu Hamza! God bless you!"

Khatib plays for Kuwait Sporting Club, his fourth team in Kuwait. Standing on the sideline of his home stadium one afternoon in February, he struggles to explain how he could think about representing Syria again, given his previous stance and the atrocities the government continues to inflict on the civilian population.

"What happened is very complicated," he says. "I can't talk more about these things. Sorry, sorry, I'm very sorry. Better for me, better for my country, better for my family, better for everybody if I not talk about that."

Assad's scorched-earth campaign in Homs included rape and starvation -- some residents ate grass to survive, according to witnesses and opposition activists. Massacres were reported in which witnesses saw Assad forces round up and kill civilians.

Khatib is one of Homs' most prominent citizens and one of Syria's most famous athletes -- a national star since his teens. He left the country in the early 2000s to play professionally in Belgium, China and, for more than a decade, Kuwait, where he broke the league's career scoring record. Khatib used his soccer earnings to help build a street in Homs -- Al Khatib Street -- complete with a soccer field and a mosque that also bears the family name. Despite the millions he earned playing abroad, he always came home to represent Syria. "To play for national team, it's 24 million watch you, 24 million support you to win," he says.

Khatib's boycott, announced at a rally in Kuwait City, was a blow to Assad. Draped in a sash with the revolution colors, Khatib told the screaming crowd: "Here in front of the media, I want to say that I will never play for the Syrian national team as long as there are bombs falling anywhere in Syria."

One man lifted Khatib onto his shoulders. The crowd addressed him as Abu Hamza, an affectionate nickname meaning "Father of Hamza," his oldest son.

"God bless you, Abu Hamza! God bless you!"

Khatib plays for Kuwait Sporting Club, his fourth team in Kuwait. Standing on the sideline of his home stadium one afternoon in February, he struggles to explain how he could think about representing Syria again, given his previous stance and the atrocities the government continues to inflict on the civilian population.

"What happened is very complicated," he says. "I can't talk more about these things. Sorry, sorry, I'm very sorry. Better for me, better for my country, better for my family, better for everybody if I not talk about that."

For other players, representing Assad is an unthinkable betrayal.

One is Firas al-Ali.

"I saw Syria as paradise on earth," says Ali, a former defender on the national team.

But he's no longer in Syria, and this isn't paradise.

The Karkamis Refugee Camp resembles a low-slung prison. Perched on Turkey's southern border with Syria, the camp is surrounded by gray walls and barbed wire and is controlled by the Turkish government. The 6,886 occupants (including 1,963 children) are free to leave, if only they had somewhere to go and the means to get there.

Ali once owned three houses. Now all his belongings are stuffed into a large white tent, one of hundreds erected symmetrically on the sun-baked earth. Ali's tent is no bigger or smaller than his neighbors', but inside it's immaculate and formal. White lace curtains line the canvas walls, and an Oriental rug covers the wood foundation. Floral-patterned cushions form a U-shaped sitting area. A small silver teapot rests atop a hot plate, and there's even a 13-inch TV and a mini fridge. Ali, 31, his wife and three children have lived at Karkamis for three years. His young daughter, Aysha, was born here.

Ali has dark hair that sweeps across his forehead and the willowy grace of a pro athlete. For close observers of Syrian soccer, his predicament is difficult to comprehend, a star athlete left to live among his fans in tent housing. Ali played for Shorta, one of the top teams in Damascus, earning $125,000 a season, a fortune in Syria. More important, he represented Syria. "From 23 million people, I was one of the 20 best players in my country," he says. "I was famous and recognized wherever I went. My material situation was excellent. I had a good family and a good reputation. I never thought of even taking a step outside my country."

Now he's a refugee, his family's needs met by the Turkish Disaster and Emergency Management Authority.

Ali says he would rather live in a refugee camp than play for Syria. In 2011, when Assad's forces attacked Hama, his hometown, Ali's 19-year-old cousin Abdullah, a college geography student, was shot and killed during a protest. "The bullet struck his eye and came out of his head," Ali says. Later, a barrel bomb -- a gas-filled oil drum the regime has heaved from helicopters by the thousands -- fell through the roof of a house and incinerated his niece as she stood in her kitchen. Ali says he arrived a few minutes later. "To see a human being cut to pieces, it's a nightmare," he says. "She was almost 200 pounds; she was heavily built. We couldn't find her." Ali joined the protests, covering his face because he was so recognizable. He felt he was leading a double life: challenging Assad in the streets and representing him on the field.

One morning Ali showed up for practice at Abbasiyyin Stadium in Damascus and found that it had been converted into a military base. "We had half of the stadium, and the 4th Division [of the Syrian Army] had the other half. This I saw with my own eyes! There was artillery in places meant for athletes. They would go out to suppress the demonstrations from the stadium that I was practicing in. I'd hear gunfire from inside the stadium. And the demonstrators still didn't have weapons. The only ones who carried weapons at that time were the regime."

The national team's head coach was Fajer Ebrahim, the Assad loyalist who later wore a T-shirt with the president's picture before a World Cup qualifying match. Ebrahim spoke openly about the need to crush the protests, Ali says. By winning games, Ebrahim told the players, Syria would show the world that the uprising was having little effect. The players were divided: "We were destroying ourselves," Ali says. He felt increasingly demoralized, his effort on the field diminished "because I was so distracted. Friends were dying, relatives were dying."

Ali sometimes stayed at the Blue Tower Hotel, a four-star hotel on Hamra Street in Damascus. One sleepless night, he says, he watched in horror from his eighth-floor window as the government shelled civilian neighborhoods around the city. "It was as though I was watching an action movie on television," he says. "It was terrifying."

Another night, while the national team was training for a tournament in India, Ali got a call that his 13-year-old cousin, Alaa, had been killed during a government attack in a village outside Hama. Thirty minutes later, he joined the national team for dinner. When one of his teammates mocked the protesters, Ali says he hurled a spoon at him before teammates pulled them apart. Ali returned to his room and called his family.

"I'm done," he told his sister.

"What do you mean?" she responded.

"I don't want to play for them, ever," he replied.

He arranged for two of his brothers to pick him up at 5:30 the following morning. From there, Ali sped off to rebel-held territories, waved through at checkpoints, he says, by soldiers who recognized him as a famous athlete but were unaware he was fleeing the regime. He crossed the border into Turkey with his young family. Ali was free, but suddenly he had new challenges. "I had money in the bank, and after I defected, the regime took it," he says. "I had three houses, and they were destroyed. ... I had a plot of land, it's gone. ... It was just like all my money went."

As he describes his transformation, Ali sits in what passes for a mall at Karkamis: a row of plywood stalls that sells everything from food to canned goods to cookware to generators. One of the vendors brings over platters of grilled meats, and Ali ducks inside one of the stalls -- a cramped hardware store -- to avoid the flies that descend on the food. His days revolve around teaching soccer to children, who flock to him like a camp celebrity. In the late morning, as the sun cuts through the desert haze, Ali and three dozen kids gather on a concrete slab strewn with broken glass to stretch, run laps and scrimmage. Occasionally the ball finds its way to Ali, who manipulates it with the practiced dexterity of his former life.

"It's hard, but I don't regret anything at all," he says. "How would one feel who is playing under this flag and carrying a picture of the person who is the sole reason for the killing and the death and the expulsion of more than 7 million Syrians?"

One is Firas al-Ali.

"I saw Syria as paradise on earth," says Ali, a former defender on the national team.

But he's no longer in Syria, and this isn't paradise.

The Karkamis Refugee Camp resembles a low-slung prison. Perched on Turkey's southern border with Syria, the camp is surrounded by gray walls and barbed wire and is controlled by the Turkish government. The 6,886 occupants (including 1,963 children) are free to leave, if only they had somewhere to go and the means to get there.

Ali once owned three houses. Now all his belongings are stuffed into a large white tent, one of hundreds erected symmetrically on the sun-baked earth. Ali's tent is no bigger or smaller than his neighbors', but inside it's immaculate and formal. White lace curtains line the canvas walls, and an Oriental rug covers the wood foundation. Floral-patterned cushions form a U-shaped sitting area. A small silver teapot rests atop a hot plate, and there's even a 13-inch TV and a mini fridge. Ali, 31, his wife and three children have lived at Karkamis for three years. His young daughter, Aysha, was born here.

Ali has dark hair that sweeps across his forehead and the willowy grace of a pro athlete. For close observers of Syrian soccer, his predicament is difficult to comprehend, a star athlete left to live among his fans in tent housing. Ali played for Shorta, one of the top teams in Damascus, earning $125,000 a season, a fortune in Syria. More important, he represented Syria. "From 23 million people, I was one of the 20 best players in my country," he says. "I was famous and recognized wherever I went. My material situation was excellent. I had a good family and a good reputation. I never thought of even taking a step outside my country."

Now he's a refugee, his family's needs met by the Turkish Disaster and Emergency Management Authority.

Ali says he would rather live in a refugee camp than play for Syria. In 2011, when Assad's forces attacked Hama, his hometown, Ali's 19-year-old cousin Abdullah, a college geography student, was shot and killed during a protest. "The bullet struck his eye and came out of his head," Ali says. Later, a barrel bomb -- a gas-filled oil drum the regime has heaved from helicopters by the thousands -- fell through the roof of a house and incinerated his niece as she stood in her kitchen. Ali says he arrived a few minutes later. "To see a human being cut to pieces, it's a nightmare," he says. "She was almost 200 pounds; she was heavily built. We couldn't find her." Ali joined the protests, covering his face because he was so recognizable. He felt he was leading a double life: challenging Assad in the streets and representing him on the field.

One morning Ali showed up for practice at Abbasiyyin Stadium in Damascus and found that it had been converted into a military base. "We had half of the stadium, and the 4th Division [of the Syrian Army] had the other half. This I saw with my own eyes! There was artillery in places meant for athletes. They would go out to suppress the demonstrations from the stadium that I was practicing in. I'd hear gunfire from inside the stadium. And the demonstrators still didn't have weapons. The only ones who carried weapons at that time were the regime."

The national team's head coach was Fajer Ebrahim, the Assad loyalist who later wore a T-shirt with the president's picture before a World Cup qualifying match. Ebrahim spoke openly about the need to crush the protests, Ali says. By winning games, Ebrahim told the players, Syria would show the world that the uprising was having little effect. The players were divided: "We were destroying ourselves," Ali says. He felt increasingly demoralized, his effort on the field diminished "because I was so distracted. Friends were dying, relatives were dying."

Ali sometimes stayed at the Blue Tower Hotel, a four-star hotel on Hamra Street in Damascus. One sleepless night, he says, he watched in horror from his eighth-floor window as the government shelled civilian neighborhoods around the city. "It was as though I was watching an action movie on television," he says. "It was terrifying."

Another night, while the national team was training for a tournament in India, Ali got a call that his 13-year-old cousin, Alaa, had been killed during a government attack in a village outside Hama. Thirty minutes later, he joined the national team for dinner. When one of his teammates mocked the protesters, Ali says he hurled a spoon at him before teammates pulled them apart. Ali returned to his room and called his family.

"I'm done," he told his sister.

"What do you mean?" she responded.

"I don't want to play for them, ever," he replied.

He arranged for two of his brothers to pick him up at 5:30 the following morning. From there, Ali sped off to rebel-held territories, waved through at checkpoints, he says, by soldiers who recognized him as a famous athlete but were unaware he was fleeing the regime. He crossed the border into Turkey with his young family. Ali was free, but suddenly he had new challenges. "I had money in the bank, and after I defected, the regime took it," he says. "I had three houses, and they were destroyed. ... I had a plot of land, it's gone. ... It was just like all my money went."

As he describes his transformation, Ali sits in what passes for a mall at Karkamis: a row of plywood stalls that sells everything from food to canned goods to cookware to generators. One of the vendors brings over platters of grilled meats, and Ali ducks inside one of the stalls -- a cramped hardware store -- to avoid the flies that descend on the food. His days revolve around teaching soccer to children, who flock to him like a camp celebrity. In the late morning, as the sun cuts through the desert haze, Ali and three dozen kids gather on a concrete slab strewn with broken glass to stretch, run laps and scrimmage. Occasionally the ball finds its way to Ali, who manipulates it with the practiced dexterity of his former life.

"It's hard, but I don't regret anything at all," he says. "How would one feel who is playing under this flag and carrying a picture of the person who is the sole reason for the killing and the death and the expulsion of more than 7 million Syrians?"

Can the national team really serve as a peaceful oasis, a place for Syrians to come together? Or is it another weapon for Assad to project normalcy and legitimize his authority?

Anas Ammo has pondered this question at length. His answer was to begin building a sports human rights case against the Syrian government. Ammo saw the project as his way to serve the opposition. He began five years ago, when he realized that athletes were among the most prominent victims of Assad's brutality and that the government was using soccer, Ammo's lifelong passion, as a propaganda tool. With dozens of athletes dead and thousands more living as refugees, Ammo believes that "a whole generation of football in Syria has disappeared."

In Mersin, Ammo operates out of a sparsely furnished two-room office with a distant view of the Mediterranean. He fled here from Aleppo, where he worked as a sports writer for Syria's Al-Watan newspaper and as a volunteer public relations official with Ittihad, the city's premier soccer club. He was working with Ittihad in 2011, he says, when the government began to compel players to attend pro-Assad demonstrations. Former players told ESPN that such orders were common. "The players were very angry at them for forcing them to go out," Ammo says. "I really felt sad when I saw sports used like this."

As the civil war escalated, the military began to use stadiums in Damascus, Aleppo, Hama, Homs and other cities as bases and detention facilities, according to former players, human rights monitors and videos taken by activists. Two videos, for example, appear to show rockets being fired from the field at Abbasiyyin Stadium in Damascus, the same facility that Firas al-Ali said players were forced to share with the Syrian Army.

Fadi Dabbas, the vice president of the Syrian Football Association and head of delegation for the national team, described the allegations as false, telling ESPN that stadiums were "never used for military reasons." He blamed Western media, which he called biased.

Anas Ammo has pondered this question at length. His answer was to begin building a sports human rights case against the Syrian government. Ammo saw the project as his way to serve the opposition. He began five years ago, when he realized that athletes were among the most prominent victims of Assad's brutality and that the government was using soccer, Ammo's lifelong passion, as a propaganda tool. With dozens of athletes dead and thousands more living as refugees, Ammo believes that "a whole generation of football in Syria has disappeared."

In Mersin, Ammo operates out of a sparsely furnished two-room office with a distant view of the Mediterranean. He fled here from Aleppo, where he worked as a sports writer for Syria's Al-Watan newspaper and as a volunteer public relations official with Ittihad, the city's premier soccer club. He was working with Ittihad in 2011, he says, when the government began to compel players to attend pro-Assad demonstrations. Former players told ESPN that such orders were common. "The players were very angry at them for forcing them to go out," Ammo says. "I really felt sad when I saw sports used like this."

As the civil war escalated, the military began to use stadiums in Damascus, Aleppo, Hama, Homs and other cities as bases and detention facilities, according to former players, human rights monitors and videos taken by activists. Two videos, for example, appear to show rockets being fired from the field at Abbasiyyin Stadium in Damascus, the same facility that Firas al-Ali said players were forced to share with the Syrian Army.

Fadi Dabbas, the vice president of the Syrian Football Association and head of delegation for the national team, described the allegations as false, telling ESPN that stadiums were "never used for military reasons." He blamed Western media, which he called biased.

FIFA's statutes, which govern organizations such as the Syrian Football Association, states that "each member shall manage its affairs independently and with no influence from third parties." FIFA has invoked the independence clause at least 24 times over the past decade, resulting in 20 suspensions from international play, in response to activity the organization perceived as government interference. In 2009, for example, FIFA suspended Iraq after learning that the government had disbanded the Iraqi Football Association and sent security agents to take control of its headquarters. In 2014, FIFA suspended Nigeria after the government dissolved the leadership of the Nigerian Football Federation after the World Cup team's disappointing finish in Brazil.

Ammo believed that the violence against players, the exploitation of teams for propaganda purposes and the use of stadiums for military purposes constituted a violation of FIFA statutes. By failing to act against Syria, Ammo believed, FIFA was "an accomplice to all the crimes that have been committed against the football players and the damage that has been inflicted on the stadiums and sports facilities."

Ammo emailed the information to a former player named Ayman Kasheet. A veteran of the Premier League, Kasheet was living in Sweden, where he had been granted residency, and was in close proximity to FIFA's headquarters in Zurich.

Kasheet travelled to Zurich to confront FIFA in August 2014. Turned away at the entrance, he decided that to have any influence he needed to assemble a full report. He took a course offered by Amnesty International on how to document human rights violations. The result was a 20-page "complaint" that built on Ammo's work, filed on behalf of "more than 2,000 athletes ... separated from the Syrian Football Federation."

Kasheet wrote the complaint in English, one of FIFA's four official languages. The document is both ungrammatical and to the point. He cites "war crimes committed by government forces in Syria against the football players and football stadiums, and the silence of the Syrian Football Federation about these crimes ... ." The complaint includes a table of 10 players believed to be in government detention and provides photos for nine. Other tables list 11 under-18 players and 20 over-18 players allegedly killed by government forces. Another section shows photos and videos of stadiums occupied by Syrian forces.

Kasheet says he tried to email the information to FIFA but received no response. He returned to Zurich and dropped off the document at the front desk, but again he heard nothing.

In August 2015, Kasheet returned to FIFA headquarters, this time with an interpreter who helped him film the encounter. After haggling with a receptionist, Kasheet ultimately spoke with Alexander Koch, FIFA's corporate communications manager.

"He says it would be so much appreciated if FIFA would follow up with the document because the only way to [apply] pressure is through FIFA because FIFA is the umbrella of this federation," the interpreter tells Koch in the video.

Koch looks mildly perturbed.

"The problem that I see is that this is nothing against ... football," Koch says.

Koch tells Kasheet that he should file his complaint with the Syrian Football Association, which can then lodge a complaint with FIFA. Kasheet tries to make Koch understand that his complaint is against the Syrian Football Association, which is supported by the Assad government.

"How can you ask the football federation to submit an official complaint when the case is being made against the Syrian Football Federation?" Kasheet later tells ESPN. "It is clear and obvious that the Syrian Football Federation is part of the government. No one would believe otherwise."

One month later, Kasheet received an email from FIFA deputy secretary general Markus Kattner, reiterating that the matter is beyond FIFA's control.

"FIFA fully supports any effort aiming to ensure that all athletes are able to enjoy practicing the game of football in a violence-free environment and we thank you for your initiative," wrote Kattner, who would end up fired for financial misconduct while serving as FIFA's finance director. Kattner added that the circumstances described in the report go "far beyond" sports.

Kasheet was crushed. "Shame on FIFA," he says during a tearful interview with ESPN in Helsingborg. "I wasn't asking FIFA to make a decision immediately. I was asking FIFA to investigate. If it's not accurate, they can ignore the information and just say no."

Ammo believed that the violence against players, the exploitation of teams for propaganda purposes and the use of stadiums for military purposes constituted a violation of FIFA statutes. By failing to act against Syria, Ammo believed, FIFA was "an accomplice to all the crimes that have been committed against the football players and the damage that has been inflicted on the stadiums and sports facilities."

Ammo emailed the information to a former player named Ayman Kasheet. A veteran of the Premier League, Kasheet was living in Sweden, where he had been granted residency, and was in close proximity to FIFA's headquarters in Zurich.

Kasheet travelled to Zurich to confront FIFA in August 2014. Turned away at the entrance, he decided that to have any influence he needed to assemble a full report. He took a course offered by Amnesty International on how to document human rights violations. The result was a 20-page "complaint" that built on Ammo's work, filed on behalf of "more than 2,000 athletes ... separated from the Syrian Football Federation."

Kasheet wrote the complaint in English, one of FIFA's four official languages. The document is both ungrammatical and to the point. He cites "war crimes committed by government forces in Syria against the football players and football stadiums, and the silence of the Syrian Football Federation about these crimes ... ." The complaint includes a table of 10 players believed to be in government detention and provides photos for nine. Other tables list 11 under-18 players and 20 over-18 players allegedly killed by government forces. Another section shows photos and videos of stadiums occupied by Syrian forces.

Kasheet says he tried to email the information to FIFA but received no response. He returned to Zurich and dropped off the document at the front desk, but again he heard nothing.

In August 2015, Kasheet returned to FIFA headquarters, this time with an interpreter who helped him film the encounter. After haggling with a receptionist, Kasheet ultimately spoke with Alexander Koch, FIFA's corporate communications manager.

"He says it would be so much appreciated if FIFA would follow up with the document because the only way to [apply] pressure is through FIFA because FIFA is the umbrella of this federation," the interpreter tells Koch in the video.

Koch looks mildly perturbed.

"The problem that I see is that this is nothing against ... football," Koch says.

Koch tells Kasheet that he should file his complaint with the Syrian Football Association, which can then lodge a complaint with FIFA. Kasheet tries to make Koch understand that his complaint is against the Syrian Football Association, which is supported by the Assad government.

"How can you ask the football federation to submit an official complaint when the case is being made against the Syrian Football Federation?" Kasheet later tells ESPN. "It is clear and obvious that the Syrian Football Federation is part of the government. No one would believe otherwise."

One month later, Kasheet received an email from FIFA deputy secretary general Markus Kattner, reiterating that the matter is beyond FIFA's control.

"FIFA fully supports any effort aiming to ensure that all athletes are able to enjoy practicing the game of football in a violence-free environment and we thank you for your initiative," wrote Kattner, who would end up fired for financial misconduct while serving as FIFA's finance director. Kattner added that the circumstances described in the report go "far beyond" sports.

Kasheet was crushed. "Shame on FIFA," he says during a tearful interview with ESPN in Helsingborg. "I wasn't asking FIFA to make a decision immediately. I was asking FIFA to investigate. If it's not accurate, they can ignore the information and just say no."

ESPN sought to interview FIFA officials about Syria and its national team, but FIFA declined the request. A spokesman sent a statement similar to the one sent to Kasheet: "Over recent years, FIFA has been made aware of allegations by several parties -- often contradicting information according to different sources -- concerning violence that has affected the practice of football in the country. While we fully understand the tragic circumstances surrounding those events, as a sport governing body we also realize that these alleged actions go far beyond the domain of sporting matters in a situation where the whole country is mired in civil war."

FIFA is prevented from acting because of "the limits of our jurisdiction and capacity to verify any allegations in such a complex setting," according to the statement.

Mark Afeeva, the London-based sports attorney who has written about how FIFA applies its independence statutes, said the evidence against Syria far surpasses other cases, including Nigeria, that have led FIFA to act. "In any other context, FIFA would be almost eager to get involved," Afeeva says.

Afeeva says FIFA "has clearly taken the view that it's in its interests to not get involved" in a political crisis that involves world powers, including the United States and Russia, the host of next year's World Cup. Taking action against Syria would require more institutional courage than FIFA has previously demonstrated, he says.

FIFA is prevented from acting because of "the limits of our jurisdiction and capacity to verify any allegations in such a complex setting," according to the statement.

Mark Afeeva, the London-based sports attorney who has written about how FIFA applies its independence statutes, said the evidence against Syria far surpasses other cases, including Nigeria, that have led FIFA to act. "In any other context, FIFA would be almost eager to get involved," Afeeva says.

Afeeva says FIFA "has clearly taken the view that it's in its interests to not get involved" in a political crisis that involves world powers, including the United States and Russia, the host of next year's World Cup. Taking action against Syria would require more institutional courage than FIFA has previously demonstrated, he says.

Mohammed al-Homsi, a media activist reached in the besieged neighborhood of Al Waer inside Homs, says he continues to follow the national team because "generally speaking, sports is the only thing connecting us with the past. I won't say the Syrian team represents the entire Syrian spectrum, but it represents the beautiful past. Sports should be kept separate from conflict."

Khatib, still acclimating to a team he has not led in five years, starts the game on the bench. South Korea takes a 1-0 lead in the fourth minute. The Syrians spend the rest of the night trying to claw their way back.

Khatib enters early in the second half. Almost immediately, the pace of the game picks up as Syria goes on the attack. The stadium is about half full. The crowd, previously buoyant, is reduced to a nervous murmur as the Syrians repeatedly threaten.

As the clock ticks down, the ball, poetically, finds Khatib to the left of the net, alone. From a distance of about 10 feet, he blasts a left footer straight at the goalkeeper's head. The keeper, Sun-Tae Kwoun, manages to get his hands in front of his face at the last second and swats the ball away.

In stoppage time, with the crowd now screaming, Khatib gets one more chance. Alone again, in almost the exact same spot, he shoots another rocket, this time aiming higher. The ball thumps against the crossbar so hard the sound can be heard halfway up the stands. But it ricochets away.

Khatib says he came back to try to lift Syria, if for only a moment, out of its unending hell. "Finally I take the right decision," he says. "I hope I can let the Syrian people [be] happy."

But not tonight. The 1-0 loss puts Syria four points out of third place with three games left, its World Cup hopes all but over.

Khatib, still acclimating to a team he has not led in five years, starts the game on the bench. South Korea takes a 1-0 lead in the fourth minute. The Syrians spend the rest of the night trying to claw their way back.

Khatib enters early in the second half. Almost immediately, the pace of the game picks up as Syria goes on the attack. The stadium is about half full. The crowd, previously buoyant, is reduced to a nervous murmur as the Syrians repeatedly threaten.

As the clock ticks down, the ball, poetically, finds Khatib to the left of the net, alone. From a distance of about 10 feet, he blasts a left footer straight at the goalkeeper's head. The keeper, Sun-Tae Kwoun, manages to get his hands in front of his face at the last second and swats the ball away.

In stoppage time, with the crowd now screaming, Khatib gets one more chance. Alone again, in almost the exact same spot, he shoots another rocket, this time aiming higher. The ball thumps against the crossbar so hard the sound can be heard halfway up the stands. But it ricochets away.

Khatib says he came back to try to lift Syria, if for only a moment, out of its unending hell. "Finally I take the right decision," he says. "I hope I can let the Syrian people [be] happy."

But not tonight. The 1-0 loss puts Syria four points out of third place with three games left, its World Cup hopes all but over.

A week later, there is more news out of Syria, and it's indirectly related to Khatib's long-ago vow not to play as long Assad was killing civilians. This time the government has bombed the rebel-held village of Khan Sheikhoun with sarin, a chemical weapon. The images are horrific: Catatonic victims foam at the mouth, their pupils constricted to the size of pinpricks. Half-naked children lie helplessly in puddles, gasping for air.

The bombs kill at least 85 people.'

The bombs kill at least 85 people.'

No comments:

Post a Comment