'Syrian army defector Salam had signed a surrender deal with the régime supposed to protect him, but after reporting for military service, he disappeared and months later was declared dead.

"He went off and never came back," his elder brother said.

Salam is one of a growing number of former rebel fighters who disappeared, died or suffered abuse at the hands of régime forces, despite signing so-called reconciliation deals in areas the government has recaptured.

At least 219 people who have signed such agreements have been detained over the past two years, including 32 who likely died because of torture or poor conditions in régime jails.

Most are residents of the southern province of Daraa, the defeated cradle of Syria's 2011 uprising.

After the Russian-backed régime retook the area in 2018, most rebels decided to stay after signing reconciliation deal.

They included Ahmad, a former rebel fighter then in his late thirties, and his brother Salam, an army defector and opposition fighter turning 26 that year.

While Ahmad chose to join a Russian-backed régime unit, Salam decided to return to military service as requested under the surrender deal, despite objections from his brother, who feared he might be detained, or worse.

"He called me to tell me he would hand himself in for military service," said Ahmad, now aged 40, using a pseudonym for fear of retribution.

"I tried to stop him, but he insisted."

Under the surrender deal, Salam had six months to rejoin his old army regiment.

Two months before the deadline, he went to a Damascus office to enlist and was never seen again.

His family was left in the dark until 2019, when the government responded to their enquiries with a handwritten note on which was scrawled his date of death and corpse number.

Ahmad refuses to believe his brother died, but says if he did, the cause was likely torture or dire conditions in jail.

"We agreed to the reconciliation agreement because we had no other way to stay safe," Ahmad said.

"I managed to protect myself, but my brother didn't and now he is gone."

An activist group in Daraa has documented the deaths of 14 army defectors since 2018.

Some were stopped at checkpoints, while others died after trying to rejoin the army, the Martyrs' Documentation Centre says.

But "the régime hasn't handed over any corpses to the families nor has it said where they were buried," according to the centre.

Diana Semaan, a researcher at Amnesty International, charged the government with breaking the terms of surrender deals in Homs, Daraa and the Damascus countryside.

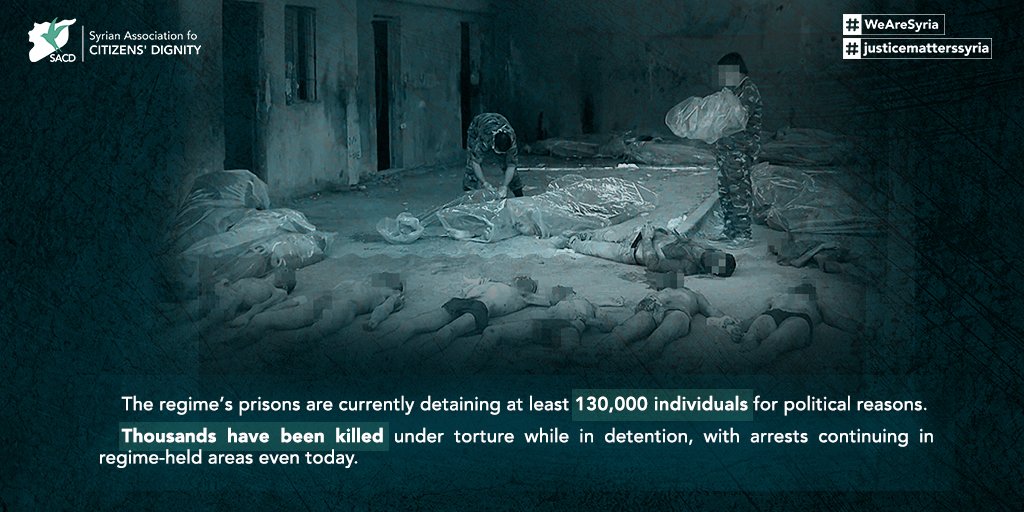

"People living in government-controlled areas, especially areas that 'reconciled' with the government, continue to be at risk of arbitrary detention, torture and death in custody," she said.

Omar al-Hariri of the Martyrs' Documentation Centre said reconciliation agreements did not include amnesty for crimes other than opposing the government.

So "the régime has fabricated criminal charges against many people" or used minor offences as a pretext to arrest them, he said.

Sara Kayyali of Human Rights Watch said ongoing detentions, torture and deaths in custody showed surrender deals were "completely ineffective".

They "are more of a facade designed to falsely reassure people, when on the ground they make very little difference," she said.

It also sends "a very bad signal" to individuals who are considering a return to government-held areas, she added.

In just one case discouraging such returns, three brothers -- two former rebel fighters -- were arrested days after they signed reconciliation deals in 2018, a source at a rights group said. They have not been seen since.

In another, as early as 2014, opposition fighter Omar, then aged 25, surrendered to regime forces after two years of siege in the central city of Homs.

He had defected from the army before joining the rebels, his brother said.

Under the surrender deal, Omar -- also a pseudonym -- was told he would be interrogated for two days, then would have to rejoin the army within six months.

But instead, he was locked up for months in a school with other former fighters then transferred to Sednaya, a Damascus prison infamous for torture.

"For four years, we paid just to make sure he stayed alive inside," his brother said.

Omar was finally released, but then forced straight back into the army with no prospect of a way out, he said.

Though "he's hoping to escape again, he feels his hands are tied." '