What's happened is that everyone knows about jihadists cutting people's heads off, and so on, they know about the movements of states, but they don't know about the remarkable things the Syrian people have done. Not many people have asked what are the Syrian people's motivations, what are their fears, hopes; what is their experience of what's happening. So in the book we've tried to amplify the voices of people on the ground. I'll give an example of why it's important before I go on. At the moment, there are over 400 local councils in the liberated parts of Syria - now by liberated I mean the areas that are not under the control of the Assad régime, and are not under the control of ISIS or Daesh or ISIL, I'm not sure what you call them in Canada; in both of those areas there is activism, but it must by necessity happen in secret underground - in the areas that are under the control of other oppositional militias, from Islamists to Free Army groups, in those areas there are over 400 local councils.

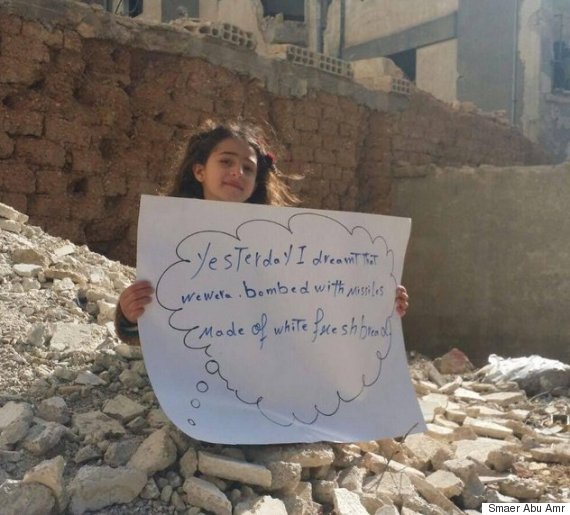

The communities have organised themselves in those areas in the most difficult of circumstances, with bombs dropping onto them, in some areas under starvation siege. They've held elections, most of these local councils are democratically elected. This is a remarkable story. There's also an explosion of popular culture, of debates, there are over 60 Free newspapers in a country where a few years ago everything was controlled by the state. Lots of Free radio stations. Lots of exciting things that are going on and happening, that we should know about. It's not often you have a real revolutionary situation in history, it's a rare historical moment, and we've kind of missed out on this one, because we've been relying on very poor journalism, and poor assumptions, because we've started from a point where we've been very ignorant about the Middle East in general, and we've missed out on this stuff which is inspiring, and interesting, and necessary for us to learn from.

At the same time, at the moment, this democratic alternative is being smashed by a full-scale international military assault. Iranian transnational Shia militias on the ground, and Russian planes cluster bombing from the sky. The country is being depopulated. There is another alternative, there was another alternative, but the Western and Eastern states seem to be collaborating in trying to crush this alternative, which we know so little about.

We've interviewed a lot of people who've been involved in these experiments. We've interviewed a lot of activists, medical practitioners, fighters, organisers, refugees, intellectuals. We've deliberately tried to amplify the voices of revolutionary Syrians, of course that's a range of revolutionary Syrians with a range of different ideas; but we've also tried to give context, because I think without context, you're just left with assumptions and ideology.

We've interviewed a lot of people who've been involved in these experiments. We've interviewed a lot of activists, medical practitioners, fighters, organisers, refugees, intellectuals. We've deliberately tried to amplify the voices of revolutionary Syrians, of course that's a range of revolutionary Syrians with a range of different ideas; but we've also tried to give context, because I think without context, you're just left with assumptions and ideology.

So we've tried to put the whole story, first into a historical context, so we start off with the history of Syria, and go to the Ottoman Empire, and then the French occupation, and then the the short experience of democracy after that, and then the rise of the Ba'ath Party, the militarisation of the Ba'ath party, the rule of Hafez al-Assad, and the neo-liberal economic reforms of the son, Bashar al-Assad; and then the revolution, how it started. How is was a wide-ranging, largely, entirely leaderless, a popular movement that involved people of all sects and backgrounds, and how that was savagely repressed, how the régime deliberately provoked a civil war and a sectarian war.

Which sounds strange to people. Why on Earth would the régime do that? Well, they did it because they've done it before. They did it in the late 70s, when there was a movement of leftists and nationalists and liberals and Islamists against them. It wasn't a huge popular revolution like 2011, but it was a movement, and they crushed it so ruthlessly that by 1982 all that was left was the armed wing of the Muslim Brotherhood, who staged an uprising in the city of Hama, and then the régime had a war situation, which they could deal with. They went in and smashed the city, and killed tens of thousands of people, destroyed the Muslim Brotherhood, and left Syrians silent for the next three decades until 2011.

So they wanted to replicate this, and how did they do it? at the same time they were rounding up tens of thousands of peaceful, non-sectarian democratic activists for death by torture, in the Spring of 2011 they were also releasing thousands of Salafist jihadist terrorists from prison. People that they'd helped to go to Iraq after 2003 to fight the Americans, but more to the point, to fight the Shia population there, which helped to start the civil war there; when these jihadists came back from Iraq, the Assad régime put them all in prison, and kept them there until the outbreak of the revolution in 2011, when it needed them again, so it sent them out. During the Spring of 2012 there was a string of sectarian massacres, organised by the régime, in the area between Homs and Hama; it was designed to create a sectarian Sunni backlash which would then in turn terrify the minority Alawi community, which the régime relies on, because 80% of the officers in the army are Alawis, because the heads of the intelligence services are Alawis.

Which sounds strange to people. Why on Earth would the régime do that? Well, they did it because they've done it before. They did it in the late 70s, when there was a movement of leftists and nationalists and liberals and Islamists against them. It wasn't a huge popular revolution like 2011, but it was a movement, and they crushed it so ruthlessly that by 1982 all that was left was the armed wing of the Muslim Brotherhood, who staged an uprising in the city of Hama, and then the régime had a war situation, which they could deal with. They went in and smashed the city, and killed tens of thousands of people, destroyed the Muslim Brotherhood, and left Syrians silent for the next three decades until 2011.

So they wanted to replicate this, and how did they do it? at the same time they were rounding up tens of thousands of peaceful, non-sectarian democratic activists for death by torture, in the Spring of 2011 they were also releasing thousands of Salafist jihadist terrorists from prison. People that they'd helped to go to Iraq after 2003 to fight the Americans, but more to the point, to fight the Shia population there, which helped to start the civil war there; when these jihadists came back from Iraq, the Assad régime put them all in prison, and kept them there until the outbreak of the revolution in 2011, when it needed them again, so it sent them out. During the Spring of 2012 there was a string of sectarian massacres, organised by the régime, in the area between Homs and Hama; it was designed to create a sectarian Sunni backlash which would then in turn terrify the minority Alawi community, which the régime relies on, because 80% of the officers in the army are Alawis, because the heads of the intelligence services are Alawis.

When we talk about context, we talk about the sectarianisation and the Islamisation, and then how foreign jihadist groups who had nothing to do with Syria exploited the chaos and came in. And how then how they were allowed to grow, because it got to the situation we are in now, where President Assad is saying, "look the choice in Syria is now between me and the mad jihadists." Most states in the world, and lot of the public in the world, because they think that is the only alternative, between him and the mad jihadists, the they think, yes we should accept what the Iranians and Russians are doing, we should maybe even help Assad get control of the country from these mad head cutters. But it was he who created the conditions for the head cutters to come in. It was his scorched Earth that helped them to come in. It was his effective non-aggression pact with ISIS for years which allowed them to grow.

Even today, over 80% of Russian bombs are not falling on ISIS, they are falling on the opposition to both Assad and ISIS. The people who have driven ISIS out of their areas before. The people that we need for any kind of serious solution in Syria, these are the people being eliminated at the moment, having the Hell bombed out of them, hundreds of thousands of new refugees to add to the more than 11 million already displaced. More than half the Syrian population. It's an enormous and expanding tragedy, and the west, through the leadership - if that's what you would call it - of the United States, Obama and John Kerry, have effectively handed Syria over to Russia and Iran. In the name of disengagement from the Middle East, which did seem like a good idea when Obama arrived in power after the Bush experience, but his done it in such a precipitous and dangerous way that takes no account of the democratic movements and revolutions in the region, the hopes of the people there, and all he's ended up doing is handing over Syria and Iraq, in effect, to even more savage imperialist powers, Russia and Iran in this case, which sadly has become a regional imperialist, and the end result is that it is such a Hell, such a mess has been formed in these two countries, the United States is not disengaged at all, it's there bombing the Hell out of Syria and Iraq, but it's bombing the symptoms, and not the cause. It's allowing the Russians to set the terms, as it' is bombing the democratic nationalist opposition, the only hope for a long-term serious settlement of the problem.

Even today, over 80% of Russian bombs are not falling on ISIS, they are falling on the opposition to both Assad and ISIS. The people who have driven ISIS out of their areas before. The people that we need for any kind of serious solution in Syria, these are the people being eliminated at the moment, having the Hell bombed out of them, hundreds of thousands of new refugees to add to the more than 11 million already displaced. More than half the Syrian population. It's an enormous and expanding tragedy, and the west, through the leadership - if that's what you would call it - of the United States, Obama and John Kerry, have effectively handed Syria over to Russia and Iran. In the name of disengagement from the Middle East, which did seem like a good idea when Obama arrived in power after the Bush experience, but his done it in such a precipitous and dangerous way that takes no account of the democratic movements and revolutions in the region, the hopes of the people there, and all he's ended up doing is handing over Syria and Iraq, in effect, to even more savage imperialist powers, Russia and Iran in this case, which sadly has become a regional imperialist, and the end result is that it is such a Hell, such a mess has been formed in these two countries, the United States is not disengaged at all, it's there bombing the Hell out of Syria and Iraq, but it's bombing the symptoms, and not the cause. It's allowing the Russians to set the terms, as it' is bombing the democratic nationalist opposition, the only hope for a long-term serious settlement of the problem.

I think the proportion of leftists who were released from prison in 2011 was very, very small, in relation to the number of jihadists. The word jihad in English only has negative connotations. When you talk about a jihadist, it immediately sounds like someone who cuts people's heads off, in order to impose a very extreme and puritanical version of an Islamic state. In Arabic the word 'jihad' just means struggle or effort. That's why you find Christian Arabs who have the name Jihad sometimes. It's a very positive word. Islamically, it means a spiritual struggle, so the first meaning of jihad is a struggle against the baser elements of your self, the struggle to be a better person, the struggle to be honest, the struggle to be a good parent, a good husband, this kind of stuff is the traditional understanding of the main meaning of jihad. Of course throughout history it has also had a warlike meaning, something that approximates to the English translation of 'holy war', and at times it's been used as a propaganda word for Muslim armies taking over other places. In the current situation I think when we are talking about the Islamists in Syria, we have to recognise there is a huge range of Islamists; and in the world, 'Islamism' is a very vague thing. It's the notion that some aspects of Islam should be applied in some way to social and political organisation. You even have some, though it's a few, leftists versions of Islamism, there's a feminist version of Islamism, there are anarcho-Islamists; these are little minority groups, but they exist, so it's a wide-ranging thing.

Now, in Syria, in terms of the militias fighting, firstly we have the Free Army groups, who I think are the people who should be getting much more consistent support, and should be allowed to have anti-aircraft weapons to defend their people from this terrible aerial assault. Those people have no political agenda other than to get rid of this régime, to defend people against the régime and its foreign backers, and then to arrive at a situation in which the Syrian people themselves can decide what happens next through some kind of democratic process.

After that you've got a group of militias who are collectively known as the Islamic Front. The most famous include Jaish al-Islam, the leader Zahran Alloush was recently killed by a Russian airstrike in the Damascus suburbs. Jaish al-Islam is strongest in some of the Damascus suburbs, in the Ghouta area. And then we also have a group called Ahrar al-Sham, which is Turkish backed. It operates mainly in the North of Syria. It's probably the most extreme of these ones in the Islamic Front. Now, the position of many revolutionaries with regard to these Islamic groups is that they are both counter-revolutionary and revolutionary at the same time. It's very complicated. In this war situation, people like me feel torn by an obvious contradiction. On the one hand, supporting these organisations in their fight against the régime and its foreign backers, and in defending their communities, which is what they're trying to do. And we recognise that they are Syrians, these are Syrian organisations, not foreign organisations, and they do have a constituency, they do represent some Syrians. They also allow local councils, women's centres, free newspapers, in the areas controlled by Syrian Islamic militias, this kind of democratic civil society is allowed to continue. There are obvious exceptions. The biggest exception is the case of the Douma 4, where four revolutionary and human rights activists, primarily Razan Zaitouneh, who our book is dedicated to, were abducted, almost definitely by Jaish al-Islam, this Islamic Front militia, in Douma, in the Damascus suburbs, and we've never seen anything of these four since. Of course, Jaish al-Islam denies doing it, they say it was the régime, or some other group, it wasn't them, but the families of these activists, and the friends of these activists, people who know, are convinced it was Jaish al-Islam. So there are these terrible authoritarian tendencies, and they've made very sectarian comments at times, which helps Assad by continuing to alienate scared minority groups from the revolution. So in this sense they are counter-revolutionary, but as I've said, they are much better than either Assad or ISIS. In a war situation, people will put up with this kind of people, and we would hope that in a future where the régime is gone, and the bombing has stopped, the civilian councils, which are allowed to operate in these areas, will call for the disarmament of such militias, and as they consist of Syrian men who are of the people, I hope they would listen.

Now I have to go on to the transnational salafist jihadists, who have a global agenda, not just a Syrian agenda, and there are two of them. There is Jabhat al-Nusra, which is the Syrian wing of al-Qaida, it is al-Qaida. And then there is ISIS, or Daesh. These two, of course, are at war with each other, and ISIS is at war with everybody. It's at war with the Free Army, with the Islamic Front, with Jabhat al-Nusra, with al-Qaida, and the states in the region, and the world. I think ISIS, because it's apocalyptic, and millenarian, and at least its propaganda is that these are the End of Days, and its declared war on everybody. It doesn't have a Syrian constituency. It's trying to engineer one, by brainwashing children in schools and so on at the moment, but it doesn't have a Syrian constuency, It's an occupation force, though many Syrians have joined up for various reasons, because they see no option, or whatever. But because it has declared war on everybody, I think that everybody will finally defeat it. If you could stop the chaos in Syria, it would naturally be defeated by the people, if you stop the bombing, and so on. Jabhat al-Nusra, traditional al-Qaida if you like, is a different matter. It has learned a lot of lessons from its past experiences, and it's been very intelligent in Syria in not trying to impose total control in certain areas. It's working in coalition with other militias, it's working inside communities. There are women's centres, for example, that are open in towns where the dominant militia is Jabhat al-Nusra. They've sometimes made trouble, but in general they haven't, because they're embedding themselves deeply in Syrian society, they're showing the tormented Syrian people, "Look, no-one has come to your aid, now the West is openly collaborating with the régime, it's agreeing with the Russian and foreign onslaught on you, and we are here as your Muslim brothers from all over the world to support you."

That's why they are better rooted in Syrian society, because no-one has sent any anti-aircraft weaponry, which would be more useful than millions and millions of pounds of charity, to the Free Army, to help them defend their communities from this constant aerial bombardment, but Muslims from all over the world have turned up and said we're willing to help. So that's a long-term danger, the abandonment of the Syrian people by the states of the world, but also by the left, who often believed silly conspiracy theories about it, and didn't engage, and didn't find out what was actually happening. And then Islamists came from abroad, and actually engaged. As a result, they've got a stake on the ground now, sadly. This is very dangerous for the Syrian people, because some of the Syrian people are Islamists, and have different ideas about different kinds of Islamic state. To some Syrian ears, the notion 'Islamic state' doesn't mean head cutting and amputations, it means good, honest, clean government, and moral government. So there are Syrians who are Islamists, but I think the vast majority of Syrians, what they would like, and we're so far from this, is a society in which they can choose, and nobody will impose upon them. What these foreign jihadist groups have in common with the Assad régime, and Russia, and Iran, and the powers of the world, is that they don't want democracy in Syria, they don't like revolutions, they don't want people organising themselves, they don't want people making their own decisions. They want to impose their ideas by force. So Syrians are now at war with all forms of authoritarianism, and it's not a struggle that is well understood, which is why we wrote the book.'

Now, in Syria, in terms of the militias fighting, firstly we have the Free Army groups, who I think are the people who should be getting much more consistent support, and should be allowed to have anti-aircraft weapons to defend their people from this terrible aerial assault. Those people have no political agenda other than to get rid of this régime, to defend people against the régime and its foreign backers, and then to arrive at a situation in which the Syrian people themselves can decide what happens next through some kind of democratic process.

After that you've got a group of militias who are collectively known as the Islamic Front. The most famous include Jaish al-Islam, the leader Zahran Alloush was recently killed by a Russian airstrike in the Damascus suburbs. Jaish al-Islam is strongest in some of the Damascus suburbs, in the Ghouta area. And then we also have a group called Ahrar al-Sham, which is Turkish backed. It operates mainly in the North of Syria. It's probably the most extreme of these ones in the Islamic Front. Now, the position of many revolutionaries with regard to these Islamic groups is that they are both counter-revolutionary and revolutionary at the same time. It's very complicated. In this war situation, people like me feel torn by an obvious contradiction. On the one hand, supporting these organisations in their fight against the régime and its foreign backers, and in defending their communities, which is what they're trying to do. And we recognise that they are Syrians, these are Syrian organisations, not foreign organisations, and they do have a constituency, they do represent some Syrians. They also allow local councils, women's centres, free newspapers, in the areas controlled by Syrian Islamic militias, this kind of democratic civil society is allowed to continue. There are obvious exceptions. The biggest exception is the case of the Douma 4, where four revolutionary and human rights activists, primarily Razan Zaitouneh, who our book is dedicated to, were abducted, almost definitely by Jaish al-Islam, this Islamic Front militia, in Douma, in the Damascus suburbs, and we've never seen anything of these four since. Of course, Jaish al-Islam denies doing it, they say it was the régime, or some other group, it wasn't them, but the families of these activists, and the friends of these activists, people who know, are convinced it was Jaish al-Islam. So there are these terrible authoritarian tendencies, and they've made very sectarian comments at times, which helps Assad by continuing to alienate scared minority groups from the revolution. So in this sense they are counter-revolutionary, but as I've said, they are much better than either Assad or ISIS. In a war situation, people will put up with this kind of people, and we would hope that in a future where the régime is gone, and the bombing has stopped, the civilian councils, which are allowed to operate in these areas, will call for the disarmament of such militias, and as they consist of Syrian men who are of the people, I hope they would listen.

Now I have to go on to the transnational salafist jihadists, who have a global agenda, not just a Syrian agenda, and there are two of them. There is Jabhat al-Nusra, which is the Syrian wing of al-Qaida, it is al-Qaida. And then there is ISIS, or Daesh. These two, of course, are at war with each other, and ISIS is at war with everybody. It's at war with the Free Army, with the Islamic Front, with Jabhat al-Nusra, with al-Qaida, and the states in the region, and the world. I think ISIS, because it's apocalyptic, and millenarian, and at least its propaganda is that these are the End of Days, and its declared war on everybody. It doesn't have a Syrian constituency. It's trying to engineer one, by brainwashing children in schools and so on at the moment, but it doesn't have a Syrian constuency, It's an occupation force, though many Syrians have joined up for various reasons, because they see no option, or whatever. But because it has declared war on everybody, I think that everybody will finally defeat it. If you could stop the chaos in Syria, it would naturally be defeated by the people, if you stop the bombing, and so on. Jabhat al-Nusra, traditional al-Qaida if you like, is a different matter. It has learned a lot of lessons from its past experiences, and it's been very intelligent in Syria in not trying to impose total control in certain areas. It's working in coalition with other militias, it's working inside communities. There are women's centres, for example, that are open in towns where the dominant militia is Jabhat al-Nusra. They've sometimes made trouble, but in general they haven't, because they're embedding themselves deeply in Syrian society, they're showing the tormented Syrian people, "Look, no-one has come to your aid, now the West is openly collaborating with the régime, it's agreeing with the Russian and foreign onslaught on you, and we are here as your Muslim brothers from all over the world to support you."

That's why they are better rooted in Syrian society, because no-one has sent any anti-aircraft weaponry, which would be more useful than millions and millions of pounds of charity, to the Free Army, to help them defend their communities from this constant aerial bombardment, but Muslims from all over the world have turned up and said we're willing to help. So that's a long-term danger, the abandonment of the Syrian people by the states of the world, but also by the left, who often believed silly conspiracy theories about it, and didn't engage, and didn't find out what was actually happening. And then Islamists came from abroad, and actually engaged. As a result, they've got a stake on the ground now, sadly. This is very dangerous for the Syrian people, because some of the Syrian people are Islamists, and have different ideas about different kinds of Islamic state. To some Syrian ears, the notion 'Islamic state' doesn't mean head cutting and amputations, it means good, honest, clean government, and moral government. So there are Syrians who are Islamists, but I think the vast majority of Syrians, what they would like, and we're so far from this, is a society in which they can choose, and nobody will impose upon them. What these foreign jihadist groups have in common with the Assad régime, and Russia, and Iran, and the powers of the world, is that they don't want democracy in Syria, they don't like revolutions, they don't want people organising themselves, they don't want people making their own decisions. They want to impose their ideas by force. So Syrians are now at war with all forms of authoritarianism, and it's not a struggle that is well understood, which is why we wrote the book.'