miriam cooke:

'I along with all the creative workers I deal with in this book, do not believe at all in the way the revolution has been characterised. So that now people are talking about a civil war, how can it be a civil war when the government is exterminating its own people? When the Assad régime has been conducting almost a genocide on his own people. So perhaps we called call it a pure war in the way that Paul Virilio refers to it, as the crushing of the people by the government. But I think it is absolutely crucial to be in solidarity with those who started the revolution, and whether they have stayed inside the country or whether they have left, their insistence is always on the fact that it's a revolution.

So, as many people will know, the Arab Spring broke out in the December of 2010 in Tunisia, and very quickly spread to Egypt and Yemen, Bahrain and Libya. And of course in the first cases, Ben Ali was forced to escape out of Tunisia, Mubarak was forced to resign, Saleh out of Yemen; and in Libya of course we had a similar situation happening to Gadaffi as happened to Saddam Hussein, ultimately found in a hole. The hole happened to be a sewer for Gadaffi.

So when these young boys in a town called Daraa, which is on the border with Jordan in the south, picking up the mood of the moment, scribbled on a wall - they were schoolchildren, returning home from school - "It's your turn, doctor", addressing themselves to Bashar Assad, who's an ophthalmologist; and then scribbling another motto or slogan that had gone around the Arab world, "The people want the régime to fall".

Unlike what had happened elsewhere, where there was in the beginning toleration for these forms of expression, artistic expression, so when El Général sang his famous song, addressing the Rais Lebled, who was Ben Ali, the head of the country, and told him, your people are suffering and you've got to go, and Ben Ali didn't punish him immediately; in Daraa it was very different.

The boys were immediately picked up, taken to the local police station, and they were tortured. News spread like wildfire across Syria, and this for me has been so interesting, the way news of demonstrations travels so quickly. People just flooded the streets, and the government cracked down. And they cracked down again and again, and the demonstrations continued. Particularly on Friday, because Friday was the only day where there was official permission for people to assemble, because of course Friday is the day of the Jumu'ah Friday prayer in the mosque.

And so the demonstrations were, in Syria, very different from the other countries, because in the other Arab Spring countries, the demonstrations in general happened in one city. usually the capital. So Sana'a in Yemen, and Cairo's Tahrir Square in Egypt, Tunis in Tunisia, Bahrain Bahrain; but here it was almost everywhere in the country that people stood up to the violence, the injustice, the radical cruel injustice, of the régime.

So that, I think, gives a timeline for the revolution that continues until today. If you talk to any of the people that I have written about in dancing in Damascus, there is not one who would not call it a revolution. On fact, a book came out, I think it was three or four months ago, Wendy Pearlman's We Crossed a Bridge and It Trembled; of the many dozens of people she interviewed, they all referred to it as a revolution as well. And in fact one of her interlocutors says, it is the international media that has destroyed the revolution by calling it a civil war.

***********************************************

The Syrian situation is really quite different from any other Arab country. Perhaps comparable, in the 90s, to the situation of Iraqis under Saddam Hussein. When I was in Syria, for seven months in 95/96, I interviewed writers, film-makers, people who had been in Hafez Assad's prisons for many years; some terrible prisons, some people refer to these Syrian prisons as among the worst, if not the worst, in the world; and art at that time that was still being produced, and again I'm thinking of art-activism as not being specifically image-making, but also telling stories, and making films and videos, it was so, so, important that one stay in the country, a country that was ruled with an iron fist, where fear dominated every aspect of everybody's life, and not to leave. Because the assumption there, and this has been true in many Arab countries, that the artist-activists feel that once they leave the country, their voice has lost an important gravitas. Because what you say, what you write, what you paint, what you shoot with a camera, doesn't have the same effect and power when it is done from the safety of London and Paris or New York. So, to stay meant to risk freedom, sometimes to risk life, to be able to speak truth to power, and for the people to see that they have among them someone who is daring to resist, and resist on their behalf.

So, there was a sense in which these artist-activists were spokespersons for the people. And I analyse this in my 2007 book, Dissident Syria, where I talk about the various ways the Hafez Assad régime tries to manipulate these artist-activists. And so I distinguish between permitted criticism, and what I call commissioned criticism. Permitted criticism is that which the régime allows to be distributed, and it can be criticism of the schools. It can even be light criticism, making fun of something that is happening in the government. And it allows for what the Syrians call tanafus, which is to breath. The translation in general into English is a pressure cooker system. That is, tension is building, building, building, among the people, and then at a certain point it comes so close to breaking into violence that something has to be done. And still the régime had calibrated those moments when things were getting to be so repressive that the system was endangering itself.

So people who were involved in permitted criticism were referred to by the people as muharij, or court jester.Yes, it makes us feel better, but anyhow this guy is never going to be punished, and this is what the régime wants this person to do, and so it is a form, a perverted form, of propaganda. Saying, well look, we have the freedom to criticise, so everything's OK.

Commissioned criticism was very different. And it was not condoned, and the outcome of such criticism was unclear. Would this person be thrown into jail? Would the passport be revoked? Would there be ways in which that person who had spoken out so bravely and outrageously against the régime; if he was not made to pay in some ways, but rather continued to live perfectly well in some ways, as in the case of someone like Sardella Wanlous, who was actually sponsored by the government to go to London for regular cancer treatment; did that turn that person into a court jester?

And so in some ways these artist-activists were between Scylla and Charybdis. Of loss of freedom or life, and on the other hand, not being taken seriously. And yet each time, they were risking everything that mattered to them.

So this was the situation in a society I had described as atomised. And there I'm using Hannah Arendt's term, that she used of course in describing in Totalitarianism, the situation in Hitler's Germany. Of course like all great books, it should apply beyond the particular case to the universal.What she talks about in Hitler's Germany, fits very well for Syria. And that is, everybody is afraid of everybody. And I'm afraid of my spouse, my parents, of my children, my teacher, my school friends. I'm afraid that they're going to write a report, that will then be sent to the mukhabarat, to the intelligence service. And so I will be punished for maybe making fun of Hafez Assad.

And so this country, which I knew in 95/96, was a country where people were afraid, pretty much, to talk out loud about anything that even had the slightest whiff of politics, lest their words be twisted in a report. And so what was extraordinary, when the revolution broke out, was to see the streets flooded with these people, who had been so atomised that they didn't dare to speak to each other.

***********************************************

When Hafez Assad died, and his son the ophthalmologist was returned from London to Damascus, he was not at all trained to be a politician. His brother Bassel, who died in a car crash in 1994, was the one who had been groomed to be leader. And because Bashar has seemed so unsuited to the task of leadership. I think Hafez Assad never really worked on grooming him for the job as he had done with his older son.

So when Bashar came to power, at the same time two other sons were coming to power, one in Jordan and one in Morocco, there was an expectation that the younger generation would change things. That there would be a transformation in the system. As there had been when Muhammed VI took over from his father Hassan II in Morocco, and when Abdullah took over from his father King Hussein in Jordan.

So for the first few months, there were a lot of new liberties. People were allowed to meet, even allowed to meet in semi-formal contexts, referred to as a mutada or a mutada yert, which are like the Paris salons of the 19th Century. People meeting semi-publicly, sometimes in homes, sometimes in clubs, to discuss pretty much whatever they liked. Bashar closed down the two worst prisons, one in Mezzeh, and one in Tadmur, which is Palmyra. And there was a sense that there was a radically new Syria in the making.

But of course what happened was that the freedoms became too much for the régime to deal with. There were a number of documents that intellectuals had put together, asking for real freedoms, not just these almost dinner-party freedoms, asking for radical change. And then, in 2006, there was a huge famine that brought the country, especially the rural parts, to the edge of rebellion.

The people had smelt freedom, had felt that they had enough power behind them that they could demand radical changes, could demand a revolution almost. And it was then that the Bashar régime started to crack down in very familiar ways to those that had been through the Hafez régime. And the reason I say that it was familiar was then when Bashar took over, as I said not trained, shaped, groomed for the job of President of Syria, he had no men and women that he brought in with him. No seasoned politicians. And so basically he just stepped into his father's shoes, and nothing around him changed in terms of the personnel. The atmosphere changed, but the people didn't change.

And so the draconian measures that Hafez Assad and his entourage had established in the country from 1970 when Hafez Assad took over until 2000 when he died, were in place, and Bashar could fall back on that old system.

While I say the wall of fear had cracked, and throughout the Arab Spring countries people talked about the wall of fear, it cracked due to the Damascus Spring, that everyone dates differently. It was at least a few months, and for some it went on until 2004. People had begun to feel what it could be like to be able to meet with each other, to not be afraid to discuss what was wrong with the system, not to anticipate that every word would be twisted and turned into some kind of indictment in a report. And so although Hafez al-Assad's men were there to replace the old draconian systems, people had tasted what it was like to be able to talk to each other.

So they were no longer as afraid of each other, no longer as afraid of the régime and the mukhabarat or the secret service. So I think that's where one can begin to see the cracks, as Leonard Cohen said, "There's a crack in everything, that's how the light comes in." And I think there was a crack in everything in the Syrian régime, and the light that came in, of course, was the revolution.

***********************************************

Artists who were already practising, some of them were painting, and in this case I'm talking about artists who had been educated in Damascus Academy of art. There were writers, particularly dramatists, who had been trained in the Syrian Academy of Dramatic Arts. They immediately began to produce work. The famous artist, I think outside the country, is the artist-activist Ali Ferzat. He had been producing caricatures for years and years and years, quite careful in terms of what Sadik al-Azm called the line between dissidence and martyrdom. So that's an important line that most of them tried to get close to, but not to step onto the other side into martyrdom.

So Ali Ferzat had always been functioning on that line between dissidence and martyrdom. And when the Damascus Spring broke out, blossomed, he started a cartoon magazine, he had a magazine called al-Domari, the Lamplighter. It lasted for two years. It was closed down, but it was full of very daring, oppositional work, and one of the images that I use in my book was one that came out during that period, I think it was around 2006 - so five years before the actual revolution broke out - and it's an image of a cell in the Tadmur Prison. Tadmur being Palmyra, or for people who don't know, in Arabic Palmyra is Tadmur. And it shows a prisoner hanging from hooks, like meathooks, from the wall. A hand has been amputated, a foot has been amputated, he's obviously dying. And seated on the floor next to him, surrounded by his torture tools, and blood from the dripping body, is his torturer who was weeping as he watches a soap opera.

I thought that this was such a remarkable image, because before 2000, even to use the name Tadmur or Palmyra Prison, was taboo. You couldn't talk about it. Those prisoners who I met when I was there and afterwards, who had either spent any time in Tadmur or Mezzeh or Sadnaya, they weren't allowed to talk about their time there. And here was this cartoon that had gone viral. So again, Ali Ferzat was one of the first to literally stick a finger to the régime. And it happened in August, so about five months after the beginning of the revolution. He was picked up, in Damascus, by some of the government thugs. They take him to a desert area near the airport, beat the living daylights out of him, and are particularly concerned to crush his fingers. Telling him: OK, you think that you can produce resistance and rebellion in the people through what your fingers produce. Your fingers will not produce anything, any more. So, he was found, taken to a prison, and somebody took a photograph of him, lying in bed, all bandaged up. So when his hands and fingers healed, which they did, beautifully, he then produced a cartoon of himself, in bed, with his fingers bandaged, and the middle finger upright, to Bashar. So this is: you think you can stop me, no you can't.

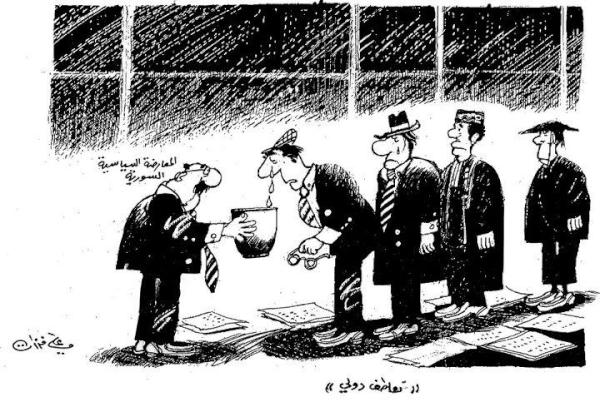

So that was one of the first really affective images that went viral. He also was the first whose work was posted to an extraordinary site called The Creative Memory of the Syrian Revolution. It's a site that was launched in early 2013, by a woman called Sana Yazigi, who is a graphic artist. She had noticed the tsunami of creative works that had been produced right from the beginning of the revolution. She designed this website; the first caricature that was posted was another cartoon by Ali Ferzat, and it's called al-Takatuf al-Duwaliya or International Sympathy, and he shows on the left, a bent over man holding out a cup, like a begging bowl; and lined up are four figures, who are obviously international leaders, one looks Chinese, another is Russian; and each one is dropping two tears into his bowl. Obviously crocodile tears.

***********************************************

There is a radical need to resist violence, and not on its own terms. You can't destroy the master's house with the master's tools. There has to be another way, and then what drives the resistance is the commitment to hope. That they will, through their works, not only assure the world that the revolution is ongoing, but that the revolution will do what revolutions do, and that is to turn the system upside down.

They can't be shut up, because in the Internet Age, whatever they put on to the web, can be silenced in one place, but will pop up somewhere else. And so I think what we're seeing here would not have been possible, even twenty years ago.Without Youtube or Facebook or blogging, it would not be possible for these artist-activists to be as empowered as they are. They're empowered by the fact - maybe if not at the beginning, certainly not long after they had started producing their works - they realised that people noticed what they were doing, that it mattered to the people inside Syria and outside Syria, that the commitment to the revolution was staunch. There was nothing that the Assad régime did to the people, to the works, that could stop the revolution.

So this theme of hope is an interesting one, and this was made explicit in the 2016 Bordeaux Festival des Arts. Every October, Bordeaux has an arts festival, and the organisers of last year's festival had heard of Sana Yazigi, and had invited her to participate in the 2016 Festival, and they asked her if she would provide thirty images from the site.

She launched the site in early 2013. Unbelievably, by the time the festival came around, there were 23,000 works on the site. She doesn't have a single piece of documentary evidence. She doesn't take photographs, unless it is is a photograph that has somehow been manipulated by someone in a creative way. Because, she says, the media is full of documentary evidence, this is not what the site is about. It is about creative memory. It is about creative memory for the future, always thinking about how people are going to look back to this period, and how will they be able to assess the role of the people who said no to Bashar.

So back to Bordeaux. She has to sift through tens of thousands of images and find thirty. And she said what became evident to her was that so many of these images were images of hope, they could be angry, the videos could be insulting - I have a whole chapter in Dancing in Damascus on insulting Bashar - but what really underscores everything that is on this site is the whole question of hope. And so she picked her thirty pieces, and the major piece for this show was a piece of graffiti, done by somebody referred to as the Banksy of Syria, and it's a graffiti he did on a broken piece of concrete, off a recently destroyed building, and it's of a little girl. She's balancing precariously, on a pile of skulls, to indicate a mass grave. And tiptoeing on top of them, she's writing the word, "Hope".

So, I thought that was one of the most inspiring, but also grimace images from this collection. And without hope, there would be no art. There would be no music. Because even out of music, there have been extraordinary developments. There is the case of Ibrahim Qashoush, who I think in 2014 [probably 2011] led a crowd in a song that can be found online. A very powerful song, that basically says, OK Bashar, just go. So he'll sing it, Yalla Erhal Ya Bashar, and the crowd then shouting it back. When you look at it on Youtube, the crowd is so huge that it cannot be contained in the image on Youtube. So enormous excitement. The next day - this happened in Hama, and through Hama runs a river called the Orontes - on the following day, in the Orontes River was found Qashoush's corpse with his throat cut.

So within a week, and this is something else that absolutely is astounding, an artist, Wissam Al-Jazairy, had produced an image, and it was an oil painting, so not something that you can throw together overnight. An oil painting of Qashoush, his throat deeply cut, blood pouring out of it, but also, flying out of it, is a bird. And the bird is the bird of freedom, and indicates, in English for the international audience that he wants, and the bird is covered in blood, but is nevertheless soaring towards freedom.

***********************************************

I had not been back to Syria since the revolution broke out, for obvious reasons, it was too dangerous, but I've spent quite a bit of time in Turkey, and a little bit of time in Beirut. I've spent quite a bit of time in Lebanon, but since the revolution only a few weeks. And in both Turkey and Beirut and in Paris, and also in Manchester, England, I've met with artist-activists, and spent time with them. There is an artists' colony in Aley. It's called Art Residence Aley. It was designed specifically for artists who are fresh out of Syria. The woman who runs it is Syrian. She's an art benefactor, an engineer also. She had to come to Beirut also, like Sana Yazigi in 2012, and because she had worked so closely with artists inside Syria, and she knew that many had had to escape, she decided that what she would do is find a place in the mountains above Beirut, so not far from the Syrian border, where she could provide the artists with shelter, materials, and the space to breathe without fear, and perhaps to produce art.

So in Aley she found an old Ottoman stable that had been pretty damaged during the civil war in Lebanon between 1975-90. And as an engineer, she converted it. She kept it very much the way it would have looked, as stables, but obviously put in a kitchen, bathrooms, and it's quite, quite, lovely. From 2012 until 2015 - I think it continues now but she moved to London - artists would be picked up from the border, somehow the message would have gotten out that the artists were making their way to or just beyond the border. She'd pick the artists up, and then take them immediately there. So by the time I got there, in the summer of 2015, there were many artists who had spent a minimum of two weeks, sometimes two months there. Sometimes alone, sometimes three or four together. And then once they had had their time up in the mountains, she then arranged for them to find places in Beirut. And it was there, through exhibitions she put together, or sometimes exhibitions up in Aley, that these artists would earn enough, to be able in some cases to go to Europe. So some of these artists, who would have remained totally internationally unknown, had they stayed in Syria - I'm not talking about during the revolution, but in general - have now become internationally famous, and a man like Tamim Alhosen, is now fetching tens of thousands of dollars for his works.

There were artist-activists in Istanbul. Not all of these artist-activists are totally behind the revolution. One that I met, Khalid Aqil, who I met while I was in Istanbul, is more concerned about contesting Islamic State, particularly the atrocities in the Yazidi region of Iraq's Mount Sinjar, than he is in saying no to the Assad régime.

I'm not at all interested in the artists that some people have said to me, what about the artists who are painting, creating works about the régime? Or how about those working with the Islamist groups, the Nusra Front, al-Qaeda, or Daesh (the Islamic State)? And what I said, is that the artists that interest me are not ones that are producing propaganda. They don't have a leader. They don't have an ideology. They don't have a blueprint for a future Syria. But they have a commitment to each other, and in that commitment to each other, a belief there will emerge a new Syria out of their work.'

No comments:

Post a Comment