'Late last year, the BBC's Mike Thomson received a desperate call from a bomb shelter in the Syrian city of Aleppo. It came from head teacher and mother of three Oum Mudar, who pleaded for help getting her terrified family out of the rebel-held part of the city. When Thomson was unable to make contact again, he feared the worst.

"The worse thing is the night, it's so long," Oum tells me, speaking after an especially heavy air attack last October.

"All the time there are rockets, helicopters, bombs. I'm so afraid for my children. I can't sleep until 5am. Before then, I just pray."

The oldest of her three children, 12-year-old Wissam, then reveals his own technique for getting through the night.

"I sometimes manage to sleep when there is bombing at night by putting my fingers in my ears. When that doesn't work I place a pillow over my head," he tells me.

But soon, as pro-government forces close in and the bombing raids get heavier, neither pillows over heads nor fingers in ears are a passport to sleep any more. What remains of rebel-held territory in East Aleppo is being pounded with unparalleled ferocity.

Just before 8pm on Tuesday 18 December, my mobile phone pings. It is a voicemail message from Oum.

"Please, please help us get out of Aleppo by safe corridor," she pleads.

"Me and my family and my neighbour… we are terrified… please help us."

Oum is a dedicated supporter of the anti-Assad revolution who has sworn to never leave Aleppo, so I know things must now be really bad.

Just before 8pm on Tuesday 18 December, my mobile phone pings. It is a voicemail message from Oum.

"Please, please help us get out of Aleppo by safe corridor," she pleads.

"Me and my family and my neighbour… we are terrified… please help us."

Oum is a dedicated supporter of the anti-Assad revolution who has sworn to never leave Aleppo, so I know things must now be really bad.

Finally, I get through. A distressing cacophony of crying children and babies comes on the line. Then I hear Oum's clearly petrified voice. She is speaking from an overcrowded basement bomb shelter, packed with distraught people, many of them children. We manage to have the following very brief and harrowing conversation.

"More than 100 people, more than 50 of them children… orphans… orphans. Their parents were killed by bombing while they were out buying food and they are all alone here."

I remember conversations in which Oum made clear that she did not expect her family to get out of East Aleppo alive. Take this chilling text message she sent me last November after a night of heavy bombing:

"We do not want anything just let us die silently .. the last breath taken out now.. we are dying..my last message."

"More than 100 people, more than 50 of them children… orphans… orphans. Their parents were killed by bombing while they were out buying food and they are all alone here."

I remember conversations in which Oum made clear that she did not expect her family to get out of East Aleppo alive. Take this chilling text message she sent me last November after a night of heavy bombing:

"We do not want anything just let us die silently .. the last breath taken out now.. we are dying..my last message."

Oum and her family are now living in Gaziantep, in the south of the country, close to the border with Syria. There, in a quiet suburb of a city that is now home to more than 300,000 Syrian refugees, I am greeted by Oum's husband, Salim, an artist. He guides me through a large ornate metal door to a bright, modern-looking ground-floor apartment.

The lack of obvious decorations or pictures on the walls suggests that either the family have not lived here long or are not planning on staying.

Oum, wearing a blue denim jacket and traditional black headscarf, greets me warmly and soon begins to talk about conditions in the basement where the family was holed up the last time she spoke to me from Aleppo.

There were more than 100 people without food or water, she says, young and old, babies crying, bombs crashing to earth nearby. There was the fear of arrest once government troops arrived, and for women the fear of rape.

The lack of obvious decorations or pictures on the walls suggests that either the family have not lived here long or are not planning on staying.

Oum, wearing a blue denim jacket and traditional black headscarf, greets me warmly and soon begins to talk about conditions in the basement where the family was holed up the last time she spoke to me from Aleppo.

There were more than 100 people without food or water, she says, young and old, babies crying, bombs crashing to earth nearby. There was the fear of arrest once government troops arrived, and for women the fear of rape.

Zane tells me that the room next door was on fire and buildings outside were collapsing. It was terrifying, he says.

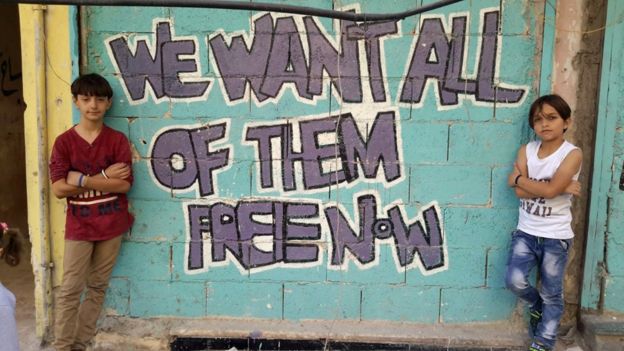

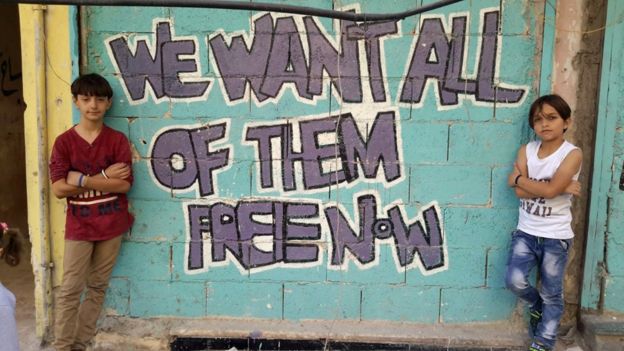

Zane's older brother, Wissam, had his own coping mechanism.

"I just closed my ears to everything and did lots of drawing," he says. "When I am drawing I forget everything around me. So I forgot the bombs, I forgot the shelling, I focused only on my drawing."

Oum remembers, around this time, seeing other families running towards government-controlled West Aleppo to escape the bombing, and trying to warn them that they might be arrested or killed.

"I shouted, 'Why do you go to death?' They said to me, 'Here is also death.' So, we have no choice."

Zane's older brother, Wissam, had his own coping mechanism.

"I just closed my ears to everything and did lots of drawing," he says. "When I am drawing I forget everything around me. So I forgot the bombs, I forgot the shelling, I focused only on my drawing."

Oum remembers, around this time, seeing other families running towards government-controlled West Aleppo to escape the bombing, and trying to warn them that they might be arrested or killed.

"I shouted, 'Why do you go to death?' They said to me, 'Here is also death.' So, we have no choice."

In the end, on 22 December, she and her family left too. They were among the last 200 people to be evacuated from East Aleppo, under a deal agreed between the rebels and the Syrian government.

Before they left, Salim remembers, they burned all of their possessions they couldn't take.

"These were our memories and we didn't want the Syrian regime to take them or abuse them," he says. "All we had left was the clothes we were wearing."

The evacuation bus took them all to Idlib. From there the family made their own way north towards Turkey, where Oum's mother had already fled. But they had to spend five days on the border, in the cold and rain, waiting for a chance to cross.

"We tried three times and each time we were caught by police," she says. "Finally we made it over the border and after three hours' walking we got to my mother's home."

Om tells me how all of them were covered in mud from head to toe and were put straight into a hot shower by her mother. A few days later, clean and refreshed, they travelled on to Gaziantep. Here, thanks to her teaching experience, Oum got a job researching children's programmes for a local television channel.

Before they left, Salim remembers, they burned all of their possessions they couldn't take.

"These were our memories and we didn't want the Syrian regime to take them or abuse them," he says. "All we had left was the clothes we were wearing."

The evacuation bus took them all to Idlib. From there the family made their own way north towards Turkey, where Oum's mother had already fled. But they had to spend five days on the border, in the cold and rain, waiting for a chance to cross.

"We tried three times and each time we were caught by police," she says. "Finally we made it over the border and after three hours' walking we got to my mother's home."

Om tells me how all of them were covered in mud from head to toe and were put straight into a hot shower by her mother. A few days later, clean and refreshed, they travelled on to Gaziantep. Here, thanks to her teaching experience, Oum got a job researching children's programmes for a local television channel.

So things worked out so much better for Oum than I had feared. The family is safe, well-fed and well-clothed - which makes me unprepared for her next statement.

"This is not my country. I can't live here, I can't," she says.

"So we decide, my husband, even my kids. We hold a meeting and make a decision to go back to Syria. There are so many kids that need me there. I still am strong. Here I'm weak. If I come back to Syria I will be more strong."

"I am not happy here because all of my memories are in Aleppo," says Wissam. "So I'll be happy to go back because at least I will be in my country."

He then adds: "To die in my own country is better than living outside of it."

Oum tells me how she has brought soil with her from the graveyard in East Aleppo where some of her relatives were buried. She plans to use it to plant "Aleppo trees" when they get to their new home from home in Idlib.

"We don't want anything impossible, just our freedom, social justice and liberty. We have the right to be free." '

"This is not my country. I can't live here, I can't," she says.

"So we decide, my husband, even my kids. We hold a meeting and make a decision to go back to Syria. There are so many kids that need me there. I still am strong. Here I'm weak. If I come back to Syria I will be more strong."

"I am not happy here because all of my memories are in Aleppo," says Wissam. "So I'll be happy to go back because at least I will be in my country."

He then adds: "To die in my own country is better than living outside of it."

Oum tells me how she has brought soil with her from the graveyard in East Aleppo where some of her relatives were buried. She plans to use it to plant "Aleppo trees" when they get to their new home from home in Idlib.

"We don't want anything impossible, just our freedom, social justice and liberty. We have the right to be free." '

No comments:

Post a Comment