'On an autumn afternoon in 2015, Firas Abdullah was relaxing at home as the familiar roar of an aircraft swelled overhead. When a bomb fell nearby and the sound of an explosion reverberated through his neighborhood, he dashed out his front door and weaved through cramped avenues.

'On an autumn afternoon in 2015, Firas Abdullah was relaxing at home as the familiar roar of an aircraft swelled overhead. When a bomb fell nearby and the sound of an explosion reverberated through his neighborhood, he dashed out his front door and weaved through cramped avenues.

But he ran in the opposite direction as everyone else.

Firas was not surprised by what he discovered at the site of the wreckage. Pipes and wood and bricks were strewn everywhere. Avalanches of debris cascaded at varying tempos. Residents searched frantically for loved ones. A corpse lay unattended in the middle of the road.

Firas took a deep breath as he scanned the destruction. A sulfuric odor penetrated his senses. He told himself to shake off the terror, to mute the cacophony of screaming, blazing fire, and wailing sirens. Then, armed with a Nikon D7100, he began documenting everything around him.

A self-taught photographer and filmmaker, Firas has taken it upon himself to chronicle the events unfolding inside Douma, a suburb of Damascus, Syria. His objective is clear: to counteract Bashar al-Assad’s propaganda campaign, which he says justifies these barrages by claiming terrorists, not civilians, are being murdered.

And so he thrust himself into the rubble, at the epicenter of the chaos, risking his life for the perfect shot — the kind that will resonate with people beyond his country’s borders. Eventually, he found it. With a decimated car, rescue workers, and a dead body in the background, he snapped a picture of an olive branch resting next to a pool of fresh blood.

As he took a minute to preview the photo on the screen of his DSLR, another roar crescendoed. It is well-known in Douma that government forces — sometimes Syrian, other times Russian — like to reappear at the scene of their initial attack to kill those who try to help victims.

Firas looked up and saw a jet soar across the sky; as everyone scattered, a missile pierced the haze and struck the earth meters from Firas, and in this moment, as he shut his eyes and a deafening boom rocks the streets, he peacefully accepted he might be meeting his end. Miraculously, he opened his eyes to realize he was more or less unscathed; the remains of a crumbling wall shielded him from the blast, undoubtedly saving his life.

Grateful for such good luck, he rushed home and uploaded JPG files to his computer. As he typed away, Firas acknowledged the war was unlikely to cease in the near future. And he recognized that the region’s most painful chapter could be on the horizon.

Nevertheless, he is steadfast in his belief that fighting disinformation, and recording what revolutionaries have endured since peaceful protests were first met with violence, must continue. “Our cameras are our weapons,” he said, “to show the world what is really going on here.”

Firas was six years old when Syrian ruler Hafez al-Assad, who assumed power after orchestrating an effective coup in 1970, became gravely ill and passed the torch to his son, Bashar. With a London-educated doctor in charge, freedom-seeking individuals in Douma — and millions more around the country — hoped the change in guard would transform Syrian into a modern nation.

The hopes for reform gradually dimmed, but as Firas navigated his way through elementary school, he wasn’t concerned with such matters. He was worried about cartoons, karate, and making his presence felt inside a home that included two parents and four brothers. He became interested in electronics, too, and in fourth grade, his father bought him his first camera:a Sony Cybershot. Through internet tutorials and his own instincts, he figured out how to frame an image, how to approach different lighting and, most importantly, how to “express the imagination” he felt.

As Firas’ hair grew long in the back and thin below his nose and lips, he became a hard-working student who also liked to socialize. Most weekends were spent partying downtown. While at home, programs in Adobe Creative Suite piqued his interest, as did shooting and editing video.

I have so many good memories from the past,” he said. “I miss the Firas I once was. I didn’t know then these were the last normal days in my life.”

Nearly 100 miles north, Miream Salameh was enjoying a life far more progressive than Middle Eastern stereotypes might lead one to expect. Although wide swaths of Syria were and remain conservative, her birthplace, Homs, was then a vibrant, cosmopolitan city — known for its religious diversity and intellectual freedom.

Born into a Christian family, Miream, now 33, never feared judgment for her beliefs, spiritual or otherwise. Instead, curiosity was encouraged: Miream visited Muslim friends at their mosques, and her Muslim friends visited her at a local church. They attended the same classes. They lived in the same neighborhoods. And they believed their different faiths were simply different paths to the same goal.

Growing up in a forward-thinking society allowed Miream to explore her creative side. When she fell in love with painting at a young age, her parents and two brothers, Johny and Suhail, supported her pursuit. She enrolled in art school, where she was introduced to an instructor named Wael Kasstoun, a renowned sculptor and painter.

“He taught me everything about life and art,” Miream recalled of her teacher. “He taught me how to think with my heart. After I knew him, I started to be a different person. I became someone who cares about others, someone who is filled with love and sees the beauty on the inside.”

Wael and Miream began spending most of their free time together, working with canvases and clay from sunrise to sunset. Miream began to see him intermittently as a second father, a third brother, a best friend. Little did Miream know that his lessons would prepare her everything that followed December 17, 2010, when a Tunisian street vendor doused himself with gasoline, lit a match, and changed the course of the Arab world forever.

The outcry in Tunisia was the dawn of what was quickly deemed the Arab Spring. Protests in Egypt led to President Hosni Mubarak’s resignation; dissent in Libya ignited a civil war that led to the death of its despotic prime minister, Muammar Gaddafi. More demonstrations took place in Oman, Yemen, Morocco — and, of course, Syria.

The conflict in Syria began in earnest when thousands in Damascus and Aleppo took to the streets in what marchers called the “Day of Rage.” Firas, then 17 years old, was in awe of the movement — its size, its message, its aspirations.

The first rally in Douma occurred on March 25. Firas chose to participate, and as a crowd assembled, he pulled out his flip phone and recorded hundreds praying in the street. The positive energy was contagious. Confidence was high. Firas had little reason to believe many of these men would be killed in the years ahead.

When Assad refused to back down and the conflict turned into a vicious war, the internet became an important resource for Syrian rebels. Cyberspace made it easy to organize, support one another, and build meaningful relationships. Syrian Facebook users eagerly created groups to chat about the cause and add like-minded people to form inclusive circles. Miream, at this point 28 and a vocal critic of Assad, logged on one day and saw a friend request from a teenager named Firas Abdullah. She immediately clicked confirm.

Once fighting took over Homs, Miream’s large informal network brought her a secret gathering at an abandoned office. There, she and a friend met a second pair of revolutionaries to discuss ways they could do more for the opposition. (Miream never learned the names of the other two; all four used aliases so, if somebody got captured, he or she wouldn’t be able to give up the accomplices while being tortured.)

They decided the best course of action was to found an anti-government magazine. They agreed on a simple name: Justice.

Miream handled the publication’s visuals. She drew caricatures meant to embarrass the regime. She took photographs of the ruin all around her. She reported the names of casualties and gathered clippings of a banned book, which preserved the journal entries of a Syrian incarcerated in one of Assad’s prisons.

More peopled started volunteering for Justice, and to the group’s delight, it gained a sizable readership among fellow dissidents. But popularity came at a cost. Roughly six months after they distributed the first issue, Miream and her colleagues were on their way to meet when they heard Assad’s forces, having caught wind of their operation, raided the office.

They didn’t let this deter them. Focused on maintaining their schedule, they moved to a makeshift bureau in the al-Shamas neighborhood. Later that afternoon, however, gang members affiliated with Shabiha — a militia loyal to Assad — stormed the neighborhood, enclosed the area, and began dragging men out of houses.

What happened next is forever burned into Miream’s memory. The officers rushed civilians into a courtyard and executed a drove of them in front of a throng of onlookers. Bedlam ensued as the shots rang out. One man died as a tank rolled over his body; about 150 more were taken into custody, and the detained women were stripped of their clothes — including their hijabs — and hauled away naked.

As arrests were being made, the magazine staff sprinted away and, to its disbelief, located an exit not manned by combatants.

“We just left everything and ran,” Miream said. “There was no other choice.”

Though Miream eluded trouble in al-Shamas, her problems were only beginning. She learned that her activism landed her name on a government list. Assad’s security apparatus had collected online images of her work and, due to her regular appearances at local rallies, pieced together her identity. Men in uniform began strolling around her neighborhood, asking passersby where she was. Whenever she saw a taxi ramble by, she was afraid an undercover henchman was behind the wheel.

Together, these tactics and anxiety culminated in overwhelming paranoia. “We believed the walls had ears,” she said.

Miream’s unease spiked when she got a vague tip that a man with cruel intentions was coming for her. Then came the direct intimidations. A barrage of strangers called her phone and, on several occasions, asked, “Do you want freedom? We [will] come to your place at night and show you freedom.”

It didn’t stop there. Anonymous Facebook accounts sent her messages filled with rape and death threats; her brother started to get those messages, too, all threatening his big sister.

Nevertheless, Miream wanted to stay in Syria. She wanted to protest, to run the magazine, to paint with Wael. But her parents didn’t share that zeal. Lots of women and girls had already been kidnapped, assaulted, imprisoned and murdered during the war, and her mom was terrified her only daughter would be poached.

The family decided it was time to leave the country. Miream begrudgingly agreed.

“My mom was right,” she said. “If I didn’t leave, I wouldn’t have made it.”

The Salamehs couldn’t bolt simultaneously, though — not without breaking the law. It was prohibited for an entire family to visit a foreign destination, so they decided to abandon their home in three waves: Miream and her brother Johny, her mom, then, finally, her dad and her other brother Suhail.

Less than two years after the winds of the Arab Spring swept through Syria, Miream and Johny packed a few bags, called a licensed taxi, and, without telling anybody, made their way for Lebanon.

Just before Miream and Johny’s departure, the Free Syrian Army (FSA) — a large rebel group directed by officers who defected from Assad’s Syrian Armed Forces — took over most of Douma. Control of the area regularly changed hands in the months, until, in October 2012, the FSA mounted an offensive and earned a decisive win over government troops, ending the back-and-forth.

Against this backdrop, Firas was wrapping up his senior year of high school. Education became his ticket out of the active war zone: Damascus University accepted him into its electrical engineering program.

But as the conflict intensified, Damascus became a dangerous place for him to live. Students’ social media activities were being monitored; thousands of arrests were taking place all over the metropolitan area. Well-aware that his criticisms of the regime could put him in peril, Firas thought he’d be imprisoned if he kept pursing a degree. And, like Miream, he sought to be a part of the revolution.

So Firas dropped out of school in 2013, returned home, and joined the FSA. He ended up on the front lines as the regime attempted to retake Douma. He weathered gun fights, assisted victims of chemical attacks, and, ultimately, helped rebels hold the city.

A year later, in October 2013, Assad’s squadrons closed off most entrances to and exits from Eastern Ghouta, besieging Douma. The rebel soldiers didn’t have to stomach as much close quarters combat, but they had to come to terms with a grimmer reality than they previously tolerated.

Physically closed off from the outside world, Firas’ family — and the rest of the ensnared civilians — wondered how long they could survive in such brutal circumstances. Where would the food come from? What about clean water? Would everyone come together in solidarity or start squabbling under pressure?

The frequency of airstrikes began to escalate. Jets tended to zero in on highly concentrated areas — markets, schools, hospitals. Organizations like Human Rights Watch had trouble delivering aid.

“We had hope it wouldn’t last long,” Firas said about the siege. “We really did.”

Once Miream and Johny exited Homs’ city limits, their cabbie negotiated a course toward Lebanon that led them straight to a checkpoint run by Syrian intelligence. Miream’s heart sank. She knew these policemen often required bribes to let travelers pass through, and she also knew there was a decent chance they would recognize her name. If the men who stopped them rummaged through her stuff, or asked to see her documents, the journey could end in a jail cell.

One of the officers peered into the driver-side window and indeed asked for a bribe. The police ordered the driver to open his trunk and began looking around. With a pit in her stomach, Miream silently prayed and tried not to think about the worst-case scenario. Yet before anyone found her possessions or thought to interrogate her, a cop reached into the pile of items, grabbed some of the driver’s glassware, held the cups to his eyes and remarked how beautiful they were.

Miream was confused by the officer’s interest in such a mundane object but kept silent. For reasons she’ll never understand, the police deemed the glasses sufficient payment and didn’t inquire about her belongings or identification. They were waved through the checkpoint and crossed into Lebanon without any more obstacles.

But, as Miream predicted, that feeling of relief gave way to more apprehension.

In Lebanon, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees didn’t provide them with the support she expected, not even food vouchers. Attempts to cooperate with other UN departments proved to be frustrating and led to dead ends. The Lebanese people weren’t particularly welcoming, either.

Slowly, her family reunited and rented a small apartment. She understood how big of a luxury that home was; lots of Syrians in Lebanon ended up in refugee camps or on the streets. Miream, along with other exiles who had beds to sleep on, dedicated herself to bringing basic resources to those struggling the most. “There was no hope there, in the camps,” she said. “There is no future, and the kids can’t have any childhoods.”

Being away from the revolution drained Miream emotionally. Her mental state only got worse when the gut-wrenching updates started to pour in. One night, she heard two Justice writers were arrested; one died in prison, while other survived his sentence and left for Turkey, then Greece, then Germany. The remaining staff chose to cease operations.

Inconsolable for long spells, Miream grieved death after death, incarceration after incarceration. Then she got the one message she prayed would never come.

Seeking to bolster pro-government propaganda, a member of Assad’s security force paid Wael a visit and asked him to paint an image of a military helmet. Wael refused. Instead, he countered, he’d be willing to draw an image focusing on a drop of blood. This enraged the officer, who scribbled a report in his notebook and stormed out.

Multiple policemen showed up at Wael’s workshop the next day, put him in handcuffs and escorted him to an undisclosed site. Outraged and terrified, his family pleaded for his release. Authorities responded by vowing to let him go the next Sunday, but the weekend passed without news on his whereabouts.

Shortly thereafter, a Homs civilian found a massive pile of dead bodies at a military hospital and identified Wael’s bone-white, emaciated corpse lying near the top. Knowing these carcasses were going to be thrown into a mass grave, the eyewitness discretely retrieved Wael so he could have the burial he deserved.

“It was so hard,” Miream said. “He was everything to me. And I couldn’t go back. I couldn’t go and stand with his wife and kids at his funeral.”

After withstanding unspeakable grief and 12 months in limbo, Miream finally caught a break. The Salamehs had extended family in Australia who knew lawyers capable of getting them out of Lebanon. They applied for visas and, following heaps of paperwork, background checks, and bureaucratic delays, accepted plane tickets to Melbourne.

Miream had yet to fully process her upcoming expedition when she faced grave danger once more.

A week prior to the flight, Miream was at a café with a friend from Syria and an acquaintance when members of Hezbollah, a militant group with considerable power in Lebanon’s government, approached and encircled them with sticks in hand.

The men started telling them they were going to torture them. Miream then saw a suspicious van outside and realized they were targets of a kidnapping attempt. She also realized that, given Hezbollah’s rank in its country, no one, not even the police, was going to protect them. She panicked as the culprit grabbed them and began slashing his stick into their arms, legs, and backs.

Miream steeled herself to be lugged away right as the assailant grabbing her was hit from behind and lost his grip. She glanced up; three men, all Syrian, had rushed over to fight off the would-be abductors. Fists flew. Insults were hurled. Miream, kneeling by the table in a daze, remembers the attackers retreating to their van.

Another close call, another escape.

A storm brewed inside Miream as the trip to Australia neared. She felt sorrow when she thought about the home she may never see again, and the friends she was going to leave behind. She felt relief when she thought about how lucky she was to get away.

“I can’t tell you that feeling, when you are happy but at the same time you are not,” Miream said. “Like, you will be comfortable and everything will be OK with you, and you will be safe, and all these things, but you don’t want to go so far from your land. Because when I fled from Syria, it wasn’t a choice that I wanted. I was forced. They forced me. It was a very difficult time.”

Soon enough, the Salamehs were gliding over the Indian Ocean.

As months passed by and the siege on Douma continued unabated, Firas grew disenchanted with the FSA. He felt like a pawn, and he detested how some politically-charged factions were poisoning the rebel cause. In 2014, he ended his service and returned to reporting, which he considered a more “pure” endeavor.

The life of an independent war journalist suited him well. Firas was brave enough to dart into mayhem, he was motivated to cover Douma relentlessly, and his technical skills improved. He cataloged fatal attacks, schoolboys embracing in front of wreckage, and the Syria Civil Defense — also known as the White Helmets — saving citizens enveloped by chunks of concrete.

One of Firas’ most harrowing days as a reporter occurred on a quiet summer morning that was interrupted by an airstrike. He was already holding his camera when the blast vibrated through his home in Douma, and he was one of the first people to arrive at the scene.

When Firas got there, he noticed an old man sitting in the back of an ambulance holding two little kids, their faces and arms caked in dust. The man, perhaps corralling his son and daughter, is gazing into the distance, his face brimming with anguish, his eyes suggesting a hint of disbelief.

While the boy peers to his right, the girl stares directly into Firas’ lens as the shutter closes. Her frightened eyes meet those of the observer.

“The children, they were so shocked they didn’t cry,” Firas said. “I took this photo for them. It was a normal attack, because the blame went out to the whole world. The girl’s eyes [cast] blame on us all.”

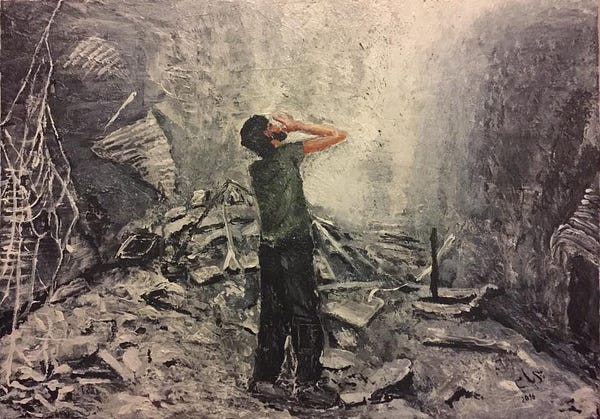

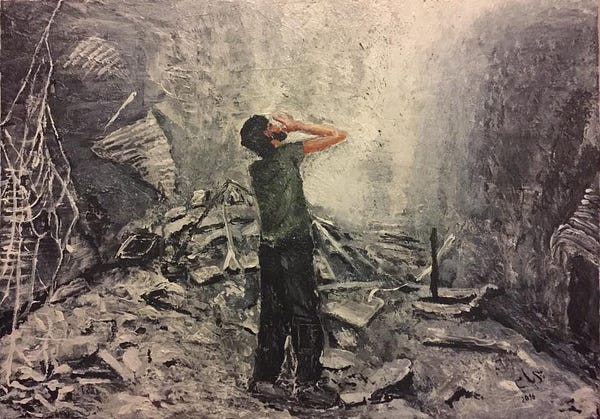

Thousands of Syrians shared the photo online. Miream was settling into her home in Melbourne when she saw the image on Facebook. She found it captivating — so much so that she decided to paint it.

Like the original, her painting of Firas’ picture received acclaim on the internet. As praise flowed in, the two struck up conversation, bonded over all they had in common, and developed an online friendship.

“His photos are so powerful but so sad at the same time,” Miream said of Firas’ work. “It’s very hard sometimes to look at them. I just cried, even when I painted that one, I cried. It was very hard to look at the eyes.”

Firas respects Miream just as much.

“Miream, she is fantastic,” Firas said. “She has a very big heart.”

Together, their creative gifts and social media acumen have started to be noticed. Large news outlets like the Associated Press, Al Jazeera, and Middle East Eye have published Firas’ photographs. When an airstrike killed more than 20 people in August 2015, the AP’s website created an entire gallery of the images he captured from the fallout. American papers, including the Seattle Times and Salt Lake Tribune, used those pictures in their coverage.

Miream’s paintings and sculptures, meanwhile, have been featured at galleries in Melbourne, Sydney, and Victoria. She’s also gone back to her activist roots as a critic of Australia’s draconian refugee policy. “The paintings really do raise awareness,” she said. “People come to me and ask me a lot of questions. ‘What is the meaning of this painting? We need to know more.’ They share in what happened in Syrian when they hear an explanation. They’re trying to speak loudly about our suffering from my art.

“Ever if I don’t speak their language, or if they don’t speak my language, it’s something everyone can understand and feel.”

Over the course of many interviews, Firas and Miream emphasized how their work is making an appreciable impact. And it is: By spreading images all over the globe — online, on walls, on aluminum armatures — they give pause to those who might not otherwise understand the Syrian tragedy. Photos and paintings and sculptures can evoke strong emotions from people young and old. Their goal, now, is to channel those feelings into action.

“I’m trying,” Miream said. “I’m trying to say a message to the whole world, to affect the people deeply, to do something together as humans. If every one of us raises the voices of the Syrian people and talks about their suffering and does a simple action, very simple, tiny action, if all of us think this way, things could be changed.”

Firas and Miream’s desire to reshape Syrian will not fade. However, both vocalized a sense of despair when discussing their country’s short-term outlook. Neither has known a Syria ruled by someone outside the strong-armed Assad family; each understands how dominant the government is, and how little the international community has tried to mitigate what is now the worst humanitarian crisis since World War II.

So while their faith in the a better future is high, the two virtual friends — one more than 8,000 miles from home, the other trapped in a precarious state — know the limitations of their power.

“It is the hardest thing, the most difficult thing that we feel,” Miream said. “We feel totally helpless. We get angry, we want to help, but we can’t do anything. Can I say the truth? I would like to go back and live in the same situation that Firas is in. Because while I live here safe, and I feel my family is safe…” Her voice trailed off and she began to cry.

“I’m sorry. I don’t know what to say. We can’t do anything.”

I asked her if she believes she’ll return to Syria and meet Firas in person.

“I always dream of it,” she said. “We need to go back and all build our country together. We only have this hope. We only have these things to think about. I always want to go back with the people who are still there. They are heroes, you know?”

“There must be a solution to stop the violence against civilians so she can come back,” Firas said. “There should be pressure on the West to find a political solution to fix this war. The solution is not with weapons or with bombs.”

The excitement in Firas’ tone is palpable when he talks about his impact abroad. Knowing outsiders appreciate his reporting lends credence to the idea that he can become a professional, full-time journalist, which is now his career goal.

He doesn’t let himself get too thrilled about that notion, though, for one’s spirits can only get so high in Douma. Especially with the way the war is shaping up in 2017.

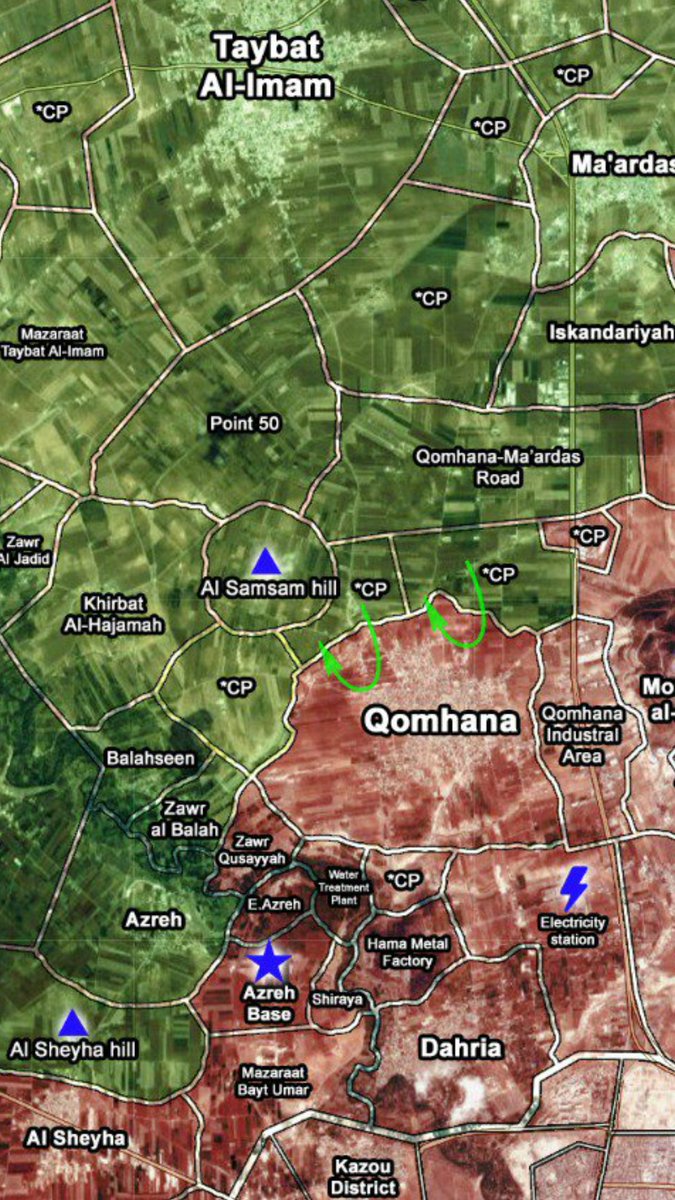

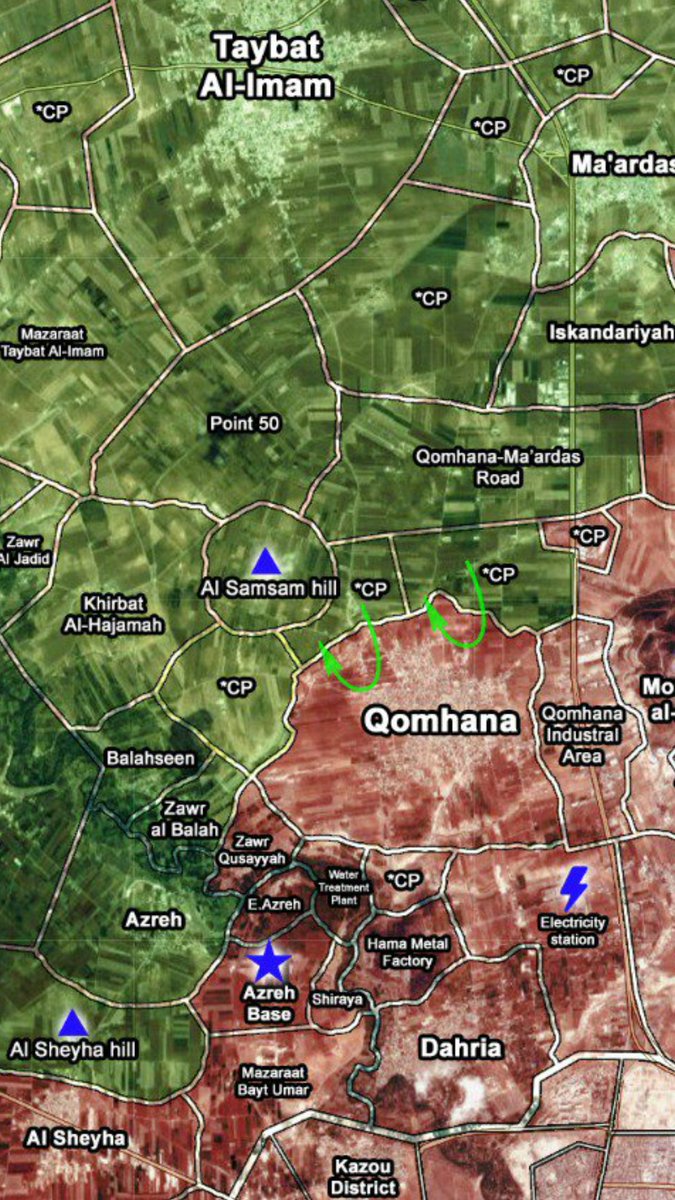

Per a December report from Al Jazeera, analysts say Assad’s regime is “planning an operation to either remove or disarm rebel fighters” in Eastern Ghouta. Because Douma is the largest rebel-held area left in the Damascus suburbs, it could be the location of Syria’s next big fight.

“We actually expect that,” Firas said. “This one will be bigger than before. We all understand it and we’re trying to get ready.”

He clarified that “get ready” means “prepare for the worst,” not take up arms. If this anticipated clash takes place, the rebels will defend themselves, but as morale plummets to lower depths with each passing day, it seems those as if they are resigned to an unfortunate end.

“For people here, death is like anything else. We lost the fear of death. Most people here have this feeling, unfortunately,” Firas said. “You cannot imagine what I am feeling about death. I’m not afraid. Death is usually here for us.”

Though Firas remains upbeat, the war has taken a considerable toll on his psyche. No longer does he get his hopes up when peace talks commence in Geneva. No longer does he anticipate ceasefires will last. No longer does he expect foreign leaders to step in to rescue his family.

And while he’ll try to report indefinitely, no longer does he have illusions about the misery Douma could soon face. “What can we do if the regime comes for us? Nothing that we can do. It’s like waiting for something to pick us up to heaven, to the sky,” he said.

“But I will keep taking photos. Always. The world must know what is happening here. I feel very proud, because I have succeeded in getting part of the reality of my life to the world. It will help to show these pictures of the revolution because they embarrass the system in front of the international courts.

“Someday, [my pictures] will be the images that show why we deserved justice and freedom. Because the camera is more dangerous than lead and iron, and our people will always be stronger than our rulers.” '

Eva J. Koulouriotis:

'If we study the Assad family regime since it came to power, we will realize its hostility, both hidden and declared, towards Christians on many occasions. The Assad regime committed massacres against the Lebanese Christians. Regime prisons were filled with Christian political detainees, both Syrians and Lebanese, especially during the civil war in Lebanon. With the start of the Syrian revolution in March 2011, Syrian Christians, like their fellow countrymen, took a stance according to their personal interests. In the first months of the revolution, many Christian young men and intellectuals declared openly their opposition to the corrupt dictatorship of the Assad regime, participating in peaceful demonstrations. When the revolution took a military nature as a result of the mad Assad regime use of its military machine against civilians, Christians were divided into three categories.

Eva J. Koulouriotis:

'If we study the Assad family regime since it came to power, we will realize its hostility, both hidden and declared, towards Christians on many occasions. The Assad regime committed massacres against the Lebanese Christians. Regime prisons were filled with Christian political detainees, both Syrians and Lebanese, especially during the civil war in Lebanon. With the start of the Syrian revolution in March 2011, Syrian Christians, like their fellow countrymen, took a stance according to their personal interests. In the first months of the revolution, many Christian young men and intellectuals declared openly their opposition to the corrupt dictatorship of the Assad regime, participating in peaceful demonstrations. When the revolution took a military nature as a result of the mad Assad regime use of its military machine against civilians, Christians were divided into three categories.

The first category stood by the Syrian revolution and joined the rest of Syrians in demonstrations. Some of them took up arms to confront terrorism of the criminal Assad forces. Some of them were arrested and are still in Assad’s prisons. Some of them were martyred in the battles, and others chose to escape and take refuge outside.

The second category included Christian beneficiaries of the Assad regime. Those shared the crimes of the Assad regime fighting in the ranks of its forces. Some Christian businessmen supported the corrupt regime because of mutual interests. Some of them were killed in the fighting and others are still trying by all means to survive. Others chose to run away, with what is left of their money after the fear of the military or political fall of the Assad regime.

The third category − which is the majority of Syrian Christians − chose neutrality. They withdrew themselves from any position of pro-revolutionary, or loyal to Assad. Most of the youth of this section immigrated and sought asylum in EU countries as a result of the great pressure exercised by the Assad regime to enlist them in the ranks of its troops.

The estimated number of Christian detainees in Syria according to international organizations and special reports is at least 3000, including women, in addition to no less than 5000 cases of enforced disappearances at the hands of Assad forces and militias loyal to him. Many of these militias have also been used against Christians in kidnapping operations for those who belong to rich families asking for ransom in return for the abducted. The number of Christians killed in Syria is not clear. However, reports talk about at least 2000 by Assad regime forces.

In some cases, the regime military bombed Christian neighborhoods to blame the Syrian military opposition in order to bring more Christians to its side. Homs has experienced a large number of these attacks.

It is a mistake that some Christians took the side of the dictator because he will inevitably go and eventually the Syrian people will be living together as they used to do for centuries.'

Jomana Qaddour:

Jomana Qaddour:

'Six long years ago, on March 15, 2011, Syrian people flooded the streets to demand their right to live free and dignified lives. They demanded freedom of expression and assembly. And they wanted to be able to advance economically without having to prove their allegiance to the oligarchy of President Bashar al-Assad.

The deepening brutality of the war steadily empowered its most radical forces, and by 2013, a growing extremist Islamist movement had hijacked the legitimate Syrian revolution. Today, both al-Qaeda and the Islamic State capture the world’s attention with their ominous flags, their international terrorism campaigns and their vicious public killings. Global public opinion seems to have largely accepted the idea that in this war there is a choice only between Assad and the religious extremists. Yet there is a third force in Syrian society that continues to hold its own, even it has been largely overshadowed by the actions of the regime and the jihadists. This is Syria’s civil society.

Over the past six years, Syrian civil society groups have achieved the impossible while operating under desperate conditions. They have created institutions of self-government and schools free of the Baathist principles that pervade the state-approved curriculum. They have organized community services such as street cleaning and food gardens. In areas where the government has cut off water supplies to punish the opposition, these grass-roots groups have even built their own water sanitation systems. It is organizations such as these that have given the Syrian people outlets to continue their activism through peaceful means, to combat authoritarianism with weapons other than guns and bullets. Instead, they offer hope, knowledge and a sense of belonging.

The world has bought into the false notion that wars are won on the battlefield. But the war of sustainable ideas in Syria is waged by its civil society groups. Instead of asking Syrians to live a life of complete allegiance to the Baathist regime, these institutions are encouraging citizens to run for local office or to engage in critical thinking about schooling. Local initiatives such as these were unheard-of under Baathist rule. As a result, many Syrians finally understand, for the first time, how it feels to take some measure of control over their lives.

I will never forget the early days of the revolution. I remember the stark image of Ghiath Matar, who passed water bottles to Syrian soldiers who were ordered to kill peaceful protesters in the town of Daraya. His actions there did much to make people aware of the Syrian Nonviolence Movement, an organization of which I am a proud member and one that has remained alive despite efforts by both the regime and the armed opposition to quell our cries for freedom.

We also have the examples of Maimouna Alammar and Osama Nassar, two brave activists who helped to establish the Violations Documentation Center, an organization that collects evidence on the cases of those who have been abused, arrested or killed — an extremely difficult task in a society at war. The Horras Child Protection Network, which also operates in besieged eastern Ghouta, provided educational and psycho-social support services to more than 18,000 children last year alone. The White Helmets, the grass-roots civil defense group, have saved more 78,000 lives and became the subject of an Oscar-nominated documentary. And then there is Abdelsalaam Dayif, a heroic doctor from Syria Relief & Development (an organization I co-founded), who travels every week between Aleppo and Idlib, providing medical aid to victims of constant barrel-bombing attacks. These are just a few of many. The list goes on.

Over the past several years, these institutions have directly confronted armed groups. In July 2016, to name but one example, civil society organizations protested the beheading of a teenage boy by members of Nour-el-Din Zenki, an armed rebel group that had previously received U.S. support. In response to the public outrage, the rebels were forced to condemn the killing.

Given the chance, there is little doubt that most Syrians would take the side of organizations such as these. They haven’t surrendered. It is because of their noble work that Assad and the Islamic State alike are targeting them, singling them out, attacking them and jailing them.

Unfortunately, the future of these organizations is now at risk — and not just because of their enemies at home. Some of these groups depend on funding from the United States, the United Nations and our European allies — funding that now may be cut.

This would be scandalously shortsighted. These are the people who will pass on the legacy of the revolution to the next generation. They will take the lead in rebuilding society so that those of differing faiths, beliefs and ethnicities can live under one flag once again. Assad will not be able to patch Syria back together because he does not have the moral legitimacy to do so. The leaders and activists of Syria’s vibrant civil society do. And they will bring Syria through its transition into democracy because that is what they have been doing since the war began. Let’s help them to continue doing it.'

Roy Gutman:

Roy Gutman: '

Mahmoud al Birkawi remembers the moment the U.S. airstrikes began in a north Syrian village. He was in the kitchen of a community building preparing the evening meal for worshippers in the main mosque who were attending the weekly religious lessons given by a moderate Islamist proselytizing group.

“We were thrown against the walls by the first strike, and then a few seconds later came the second, and the ceiling fell on us,” he said. He and others were buried under three meters of dust and debris, he said.

The miracle on March 16 was that the religious lesson had gone on 15 minutes longer than expected, delaying the arrival of 200 worshippers at dinner. “If they’d all been at the restaurant, no one would have come out alive,” said Birkawi.

At least 29 people died and 26 were wounded in the attacks on Al Jinah village, according to the White Helmets rescue group. Two independent Syrian news agencies put the death toll at 50, as did the Local Coordination Committee in nearby Al Atarib.

It did not attract much international attention—certainly not like the U.S.-led bombing of the hard-fought battleground in Mosul, where Amnesty International has said the Coalition has done too little to protect civilians, and U.S. Secretary of Defense James Mattis has declared that nobody tries harder than the U.S. military to avoid such casualties.

Perhaps. But the evidence suggests that something went very wrong in Al Jinah.

The U.S. Central Command said the attack was “an airstrike on an Al Qaeda in Syria meeting location” in Idlib that killed “several terrorists.” Idlib has “been a significant haven for Al Qaeda in recent years,” the statement added. (In fact, the airstrike occurred in Aleppo province.)

Col. John Thomas, the CENTCOM spokesman, said it had been a “precision strike,” and there was no indication that civilians were in the building. “We knew there was going to be a meeting of Al Qaeda operatives in a significant number,” he said. “What we expected to happen happened. We took the strike.” But he said CENTCOM is looking carefully into reports of civilian casualties.

Central Command was adamant. “We struck who we intended to strike,” said Thomas. “We had good intelligence on who they were and when the meeting was going to be.”

This was one of three incidents in less than a week in Syria alone that raise questions about the quality of U.S. intelligence. A Coalition assault on a school in the town of Mansoura, west of Raqqa, killed at least 23 people and injured 50, all of them civilians, according to the Smart News Agency. Other reports put the number as high as 100. But top commander for the operation, Lt. Gen. Stephen Townsend, said the bombing was under investigation but his initial reading was that it had been a “clean strike” against 30 or so ISIS fighters. “We struck enemy fighters that we planned to strike there,” he told reporters Tuesday.

The next day, some 40 civilians were killed and were 55 wounded in a coalition raid that hit a bakery in the town of Tabqa, also west of Raqqa, the Smart News Agency reported. The Command had no immediate comment on the bombing of the bakery.

The U.S. military in 2014 and 2015 mounted airstrikes against what it calls the Khorasan group in Al Qaeda, but commanders throughout the U.S.-supported Free Syrian Army rebels say they had no knowledge of its existence.

In April 2016, the U.S. spokesman for Operation Inherent Resolve, the U.S.-led coalition fighting the so-called Islamic State and Al Qaeda, asserted that fighters of what was then called the Nusra Front, the Al Qaeda affiliate in Syria, were the dominant rebel force in Aleppo.

“It’s primarily al-Nusra who holds Aleppo,” Col. Steve Warren told reporters. But when challenged to check with his intelligence experts, he acknowledged he was wrong. “I was incorrect when I said Nusra holds Aleppo,” he said in an e-mail to this reporter. “Turns out that current read is that Nusra controls the northwest suburbs” and other groups control the center,” he said.

But Warren had no information about the Nour al-Din Zinki movement or other rebel groups that had been playing a bigger role in Aleppo.

The other issue is whether Al Qaeda even exists in Syria, and if it does, what activities it has undertaken that threaten U.S. and other western interests. Last July, the Nusra Front announced it had broken with Al Qaeda and changed its name to Jabhat Fateh al Sham, and more recently it renamed itself Hayat Tahrir al Sham. But it has not been accused of operations or plotting against international targets under any of these names since announcing its separation from Al Qaeda.

The CENTCOM spokesman did not respond directly when asked. What would help answer the questions is “the specific intelligence of the sort we cannot make public,” he said.

Eyewitnesses contacted by The Daily Beast, all of whom were wounded at the Al Jinah airstrikes, disputed U.S. assertions that Al Qaeda members were present at the March 16 meeting. They said the prayer meeting was held regularly on Thursday evenings in Al Jinah, using the town mosque as well as a building built by the Da’awe order, which contains the restaurant, a second mosque and empty space above the mosque housing internally displaced.

Those attending come from villages in the western and southern countryside of Aleppo, said Birkawi, who was displaced from Aleppo. “We don’t know everyone who comes to the lesson, but we know many. Our task is to encourage people to keep on the right ethical path,” he said. He said if fighters from the Free Syrian Army attend, they are out of uniform.

Sheikh Abu Muhammad Fantash, one of the leading imams in the Da’awe and Tabligh group, also rejected any link with Al Qaeda. “We don’t belong to anyone. We are not part of any group, and we don’t have any connection with any other group,” he told The Daily Beast. “We are preachers who try to lead the people to the path of the almighty Allah.”

Fantash was wounded in the strikes and buried under the rubble, and had to be carried out by stretcher. “It was the mercy of Allah that gave me more days to live and another chance to continue in life as his obedient servant,” he said.

A third eyewitness, Suleiman Al Assi, a Da’awe activist from Jinah, made the same point. “We don’t belong to any political party or fighting group. We never interfere in politics or issues in dispute. We don’t speak about illnesses, we only speak about medicines.” All three were baffled, they said, by the American targeting.

“We are all bewildered by why the Americans or the Coalition warplanes bombed this mosque. It is a mosque and those who were inside were normal worshippers. Isn’t it enough that the Russians and the regime warplanes destroyed mosques, bakeries, hospitals and all the requirements for life?” he asked.

Muhammad Fadilah, head of the Aleppo Provincial Council, described Da’awe as a moderate group that urges Syrian Muslims to uphold spiritual values. “Like old priests, they roam and spread good tales,” he said. “They are known to visit remote villages in groups of seven or eight to urge people to take the right path. How could people like these be accused of advocating terrorism?” he said. “These are people who are against violence…they only urge people to follow a path to religiosity.”

As for a meeting of Al Qaeda: “We have heard nothing about any such meeting,” he said. “If someone wants to hold secret meetings, they have tunnels and underground facilities to do that. But he said Nusra wouldn’t work with Da’awe, because its adherents view Da’awa as “tellers of tales.” '

'In a recent interview with Al-Mayadeen television, Hezbollah’s number two Sheikh Naim Qasssem insisted that “Hezbollah would be the one deciding when to leave Syria, “which will take place when the party is guaranteed that ‘Syria as a resistance’ will remain.”

Qassem refers to the prominent role played by Syria in the “resistance axis” which opposes western interests, specifically the United States and Israel, and is headed by Iran with Hezbollah as the leading militant group based in Lebanon. The survival of this axis and pro-Iranian Syria is critical for Hezbollah and Iran. First, Syria provides Arab legitimacy to this anti-Western coalition. Second, Syria is an essential military supply line linking Iran to Hezbollah in Lebanon, which provides Iran with access to the ongoing Arab-Israeli military conflict and the Mediterranean region.

Since the beginning of the Syrian civil war, the Alawite regime of President Bashar Assad faced off against a largely Sunni opposition. The regime relies heavily on Hezbollah as a militant Shia organization to defend its position. Hezbollah was one of the first groups to spearhead pro-regime foreign legions between 15,000 to 25,000 fighters and comprised of Shiite factions from Iraq, Pakistan, Iran, and Afghanistan.

Hezbollah plays a highly versatile role in Syria. The Lebanese organization initially provided expert support to Assad in its crackdown on protestors. In 2011, Lebanese media started publicizing the death of Hezbollah fighters in Syria. The role of Hezbollah evolved to encompass offensive strategy during battles and much needed training to militias shoring up the Syrian regime.

Interviews with Hezbollah and members of the opposition attest that in many cases, Hezbollah was leading ground assault force in battles, and this first began during the 2013 battle of Qusayr. In an interview that same year, a Hezbollah fighter admitted: “Hezbollah is leading operations in Qusayr; the Syrian army is only playing a secondary role, deploying after an area is completely 'cleaned' and secured.” According to a report by the Institute for the Study of War, the Syrian government used Hezbollah fighters as a reliable infantry force alongside its own heavy weapons and airpower. In the battle of Qusayr, and on other war fronts in 2015 and 2016, military operations typically started with shelling followed by the infiltration of irregular units, and infantry attacks. Similar techniques were used as well in Zabadani and Aleppo. In Aleppo, Hezbollah played a threefold role according to interviews by the author with a Hezbollah commander who explained that the militant group headed the offense teams, which were followed by a demining team and a stabilization team.

In addition to its offensive strategy, Hezbollah has helped the regime in developing its irregular forces as well as financing and providing training to local militia groups as needed. According to researcher Aymen Jawad Tamimi, these local militias include Quwat Rhidha, the National Ideological Resistance (NIR), Liwaa al-Imam al-Mahdi, Junud Mahdi, and the Mahdi scouts among many others. Tamimi believes that Quwat al-Ridha is the core nucleus for Hezbollah in Syria and seems to be operating under the leadership and supervision of Hezbollah in Lebanon. Quwat al-Ridha includes Shia and Sunni hailing from countryside areas around cities such as Homs, Aleppo, Daraa and Damascus.

In an interview with Maan Talaa, researcher on pro-regime militias from the Turkey based think tank Omran Dirastat, Talaa adds that Quwat Ridha is estimated at 3,500 fighters and its military leadership is headed by Syrians, but the organization is financed and trained by Hezbollah. According to Talaa, two other groups can be directly linked to Hezbollah, the Liwaa al-Imam al-Mehdi and Assad Allah Ghaleb. Talaa underlines that Liwaa al-Imam al-Mehdi is also estimated at 2,000 fighters and mostly Alawites. “Assad Allah Ghaleb played a role in Ghouta, but they appear to have been decimated in battles,” explains Talaa. The Omran Dirasat researcher emphasizes that many other groups partner with Hezbollah and Iran. “In such cases, Iran generally bankrolls the groups while Hezbollah provides training,” he points out.

A Hezbollah trainer admitted in an interview that while thousands have been trained across Syria, some 10,000 were trained in Qusayr alone, the largest training facility for Hezbollah on the border with Lebanon.

Hezbollah appears well positioned in Syria for the next few years. The author interviewed Hezbollah fighters who were divided as to their long term role in Syria, but most agreed that they would not be leaving strategic regions anytime soon. “We will retain control of areas with a military importance such as Qusayr. Other spots around Homs which were given up to the Syrian army and were later lost will also stay in our hands,” says one fighter in a recent interview.

Hezbollah’s involvement in Syria has resulted in a high human cost, with 2,000 to 2,500 killed and some 7,000 injured over the last six years, according to an interview with anti-Hezbollah activist and researcher Lokman Slim. Numbers are difficult to verify with areas besieged by Hezbollah across Damascus, Homs, Aleppo, and Daraa. Yet, such human losses do not appear to have reached a tipping point for Hezbollah. The party has successfully convinced its popular base that its involvement in Syria and its fight on “terror” has shielded Lebanon from radical groups. The efficient crackdown post -2015 on terror networks by Lebanese security services has quieted criticism by Hezbollah constituents, after terror attacks dropped from a monthly occurrence to a near-zero incidence rate.

Recent gains have also played in favor of the organization. The fall of Aleppo dovetailed by internal clashes within the Syrian opposition, have improved the credibility of Hezbollah with its constituents in Lebanon.'

'The people of Al-Bab are busy bringing the northern Syrian city back to its former state following its liberation from Daesh. Civilians have been returning to their homes since Turkish-led Operation Euphrates Shield removed the terror group in mid-February. The city's population, which was once down to almost 20,000 under Daesh, has recovered to around 80,000. Al-Bab now looks like a massive construction site, according to an Anadolu Agency reporter in the area.

'The people of Al-Bab are busy bringing the northern Syrian city back to its former state following its liberation from Daesh. Civilians have been returning to their homes since Turkish-led Operation Euphrates Shield removed the terror group in mid-February. The city's population, which was once down to almost 20,000 under Daesh, has recovered to around 80,000. Al-Bab now looks like a massive construction site, according to an Anadolu Agency reporter in the area.

One returnee is Sherif Konli, who lost two relatives in the fight against Daesh.

"We are rebuilding our homes. I hope Bab will see better days and we will live a more peaceful and free life."

Ahmed Bushi is another resident who has almost completed the re-construction of his house. Until the work is finished, he and his family will be staying at a neighbor's house, which he says is in better condition. Daesh terrorists seized most of their furniture and goods, after which his home was destroyed in an aerial attack, he says.

"My only consolation is that we are still alive; property can be earned again," Bushi added.

"Bab will see its old days again," he said and expressed gratitude to the Free Syrian Army (FSA), which also helped civilians fix the city’s infrastructure after the terror group was driven out.

Turkey has also given all kinds of support to the people of Al-Bab to help normalize life in the town and to ensure residents can safely return to their homes. Since late August, Turkey has been carrying out a military operation in northern Syria. Led by FSA fighters, Operation Euphrates Shield aims to improve security, support coalition forces and eliminate the terror threat along the Turkish border.'

'500;000 displaced people arrived in FSA controlled "Euphrates Shield" -strip at border to Turkey so far from all areas of Syria.'

[https://twitter.com/markito0171/status/846278759292514304]

Julian Röpcke:

Julian Röpcke:

'Less than a week ago, Syrian rebels launched a surprise blitz on Assad regime-held towns in northern Hama province. Though it is not yet clear what the aim of the offensive would be, the rebels captured 16 towns and strategic locations of which so far the regime’s allies from Iraq with the help of the Russian air force could only recapture one small town (Kawkab).

The offensive was executed by a wide rebel alliance, ranging from Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) – listed as a terror organization in the EU and US – to moderate brigades of the Free Syrian Army. While critics reason that the Hama push is merely an “al-Qaeda offensive”, this has no basis in fact. It is true that HTS makes the largest groups participating and that suicide bombers paved the way into Souran and other locations. Still, HTS would have no chance if not supported by moderate rebel groups, using strong weapons systems like TOWs and Grad missiles – all foreign-supplied.

So, liked or not by actors abroad, Syrian rebel groups launched a united offensive that could only be as successful as seen because units cooperated beyond ideological differences.

The regime and Russia reacted in their well-known way: Brutal and rogue. While Russian jets and Iraqi militias – so far – showed only little capacity to push back rebel forces at the front, their air-dropped bombs and artillery systems hit opposition-held towns far behind the front in Idlib and Hama provinces, targeting educational institutions, hospitals and civilian homes. Dozens of innocent people got killed in conventional and chemical weapons attacks, a tactic aimed at breaking the will of the rebels by killing their families far from the fighting fronts.

But will the offensive unblock the diplomatic and military deadlock engulfing the country since the Turkey-Russia-Iran Astana negotiations and the alleged ceasefire that started late last year? Several factors indicate some strategic movement.

While Assad never stopped trying to advance in East Ghouta and west of Aleppo since January, groups under Turkish influence widely adhered to the negotiated ceasefire. But as the regime did not stop its offensives and Russia moved closer to the Turkish border, providing the YPG west of Manbij and recently in Afrin with de facto protective shields against Turkey, Ankara seems to have run out of patience with a “ceasefire” that only benefitted pro-Assad parties.

The Hama offensive with all its participating groups and seemingly recently-arrived permissions and weapons shows that the rebels still have the ability to advance and even hold ground against an apparently superior Assad-Russia-Iran alliance – when working together and getting the logistical support needed to do so. At the same time, the offensive is not likely to signal the beginning of a general U-turn in dynamics and it remains to be seen if rebels can hold the land they captured, let alone further advance as thousands of Shia militants reinforced weak Assad militias in the area.

But it is a distinct indication that outside actors, supporting Syrian opposition groups, are not (yet) willing to accept a creeping victory by Iran and Russia and their proxy Assad on the ground in Syria. The message to the Assad coalition is clear: If you keep ignoring the ceasefire like you did over the past two months, it will not hold and you will suffer under it like the people you keep attacking do. The question remains however if this message reaches its intended recipients and if they are able and willing to react differently than applying more military force and killing more innocent civilians.'

'The Syrian opposition rejects terrorism and is "fed up" with banned militants but they cannot be stopped if Syria continues evicting populations of besieged areas, opposition negotiator Basma Kodmani said on Sunday.

'The Syrian opposition rejects terrorism and is "fed up" with banned militants but they cannot be stopped if Syria continues evicting populations of besieged areas, opposition negotiator Basma Kodmani said on Sunday.

Syria's government has always cited the fight against terrorism to justify its part in a six-year war that has killed hundreds of thousands, and brands all its opponents and their backers as terrorists and sponsors of terror.

The opposition's chief negotiator Nasr al-Hariri, who is trying to negotiate an end the rule of President Bashar al-Assad, began this month by saying its stance against terrorism was proven on the battlefield and not mere words.

But subsequently rebel groups launched an offensive spearheaded by suicide-bombers from the jihadi Tahrir al-Sham alliance.

Tahrir al-Sham includes fighters who formerly belonged to the Nusra Front, once an al Qaeda affiliate and - along with Islamic State - one of the two groups in Syria designated as "terrorists" by the United Nations.

Kodmani, in Geneva for U.N.-led peace talks, said the opposition's stance was "unambiguous condemnation, disassociation from, and willingness to fight the terrorist groups" designated by the U.N.

"The fact that Nusra or Tahrir al-Sham puts itself in those battles does not mean in any way that this is a new alliance or a renewed alliance."

The militants liked to elbow their way into prominent roles but they never led an offensive on their own or maintained a ceasefire line, she said.

"We are fed up with Nusra. They are the biggest danger inside the areas where the opposition is sitting. But if you are bombed from above, you just have to postpone the battle against extremists, even though they are a mortal danger for you.

"The day the international community gives us anything to work with, believe me, the opposition will immediately turn against all the extremists and expel them from their areas."

The recent offensive was launched by local armed groups to prevent forced displacement, Kodmani said.

Forces loyal to Assad have used the tactic of forced displacement repeatedly in the past year, especially in Aleppo, starving and bombarding besieged areas until the local fighters agree to leave in what is effectively a surrender.

The U.N. Commission of Inquiry on Syria has said such displacements are war crimes. Kodmani said the international community was doing nothing to stop them.

"What options is the international community giving the population, for God’s sake? What can we tell people on the ground? Don't use force? They only have force," she said.

"This is not about terror and about working with terrorists. It's about who protects civilians."

Both Assad and the opposition hope U.S. President Donald Trump will see them as his ideal partner against terrorism. Kodmani said there was growing understanding in the U.S. administration that working with Assad meant working with Iran-led militias that do much of the fighting for him.

"I am hoping that in the next two or three months, before the summer, we will have a clear U.S. policy that sees the obvious, which is that this country cannot be put back together if the Iran-led militias remain," she said.

"We cannot get the jihadis out, we cannot have the moderates fight the extremists, if we do not have a ceasefire and Iran-led militias included in the call for withdrawal of all foreign fighters." '

Asaad Hanna:

Asaad Hanna:

'Clashes returned last week in the heart of the Syrian capital Damascus after nearly three years of silence and tranquility that had reigned over the capital. Syrian opposition forces had revived their efforts to re-open a front in the capital Damascus, through the Jobar Neighbourhood as well as in Hama province.

Leading the operation was “Faylouq al Rahman” who represent the Free Syrian Army in addition to Ahrar al Sham. In a few hours the Syrian opposition managed to break the regimes defences claiming they took control of the Al Abbasiyeen Garages. This led to a state of emergency being declared and the immediate halting of all state operations across the capital, due to the state of panic and anxiety which spread among members of the army and its affiliated militias. Moreover, control of the Autostrad highway which connects Damascus to the rest of Syria’s governorates, had also been assumed by opposition forces which caused traffic delays to and from the capital. The seizure of Jobar and Qaboun also lead to the opening of the Qaboun area which had been under regime-siege.

Two weeks back Faylouq Al Rahman announced the beginning of the second stage of the battle dubbed “Servants of God Stand your Ground” after targeting Assad’s forces with car bombs. After which Rahman’s forces headed towards the industrial area of Damascus and seized several buildings and corporate properties close to Jobar.

This battle comes in the middle of March which is a symbolic time marking the sixth year of the Syrian revolutionary struggle. It comes at the same time that the Syrian regime started ingraining itself in other opposition held areas in the city of Homs and the surrounding areas of the capital Damascus – which had spread a sense of pessimism to some, that the revolution had come to an end.

Rebel groups timed this assault just days after the termination of the Geneva talks to reaffirm the idea that its militant factions can still operate significant strikes at the core of the security establishment whilst negotiations are underway. As such the opposition would not accept a political solution from a point of weakness or with an inability to confront and kill its adversary. On the contrary the assault was purposed to leverage a political solution that the opposition hoped would lead to the fall of the regime. The battle for Damascus has sent a clear message to the chief negotiators in the United Nations and in the West. The message is that the Syrian opposition will persevere in its fight until there is either a decisive military victory or a political solution that is suitable to the needs of the revolution.

This battle has also provided an opportunity to the political wing of the Syrian opposition to strengthen its bargaining position. This derives from the school of thought which underpins the principle that “he who is stronger on the ground is stronger on the negotiating table”. As such the High Negotiations Committee now has greater leverage to enforce its conditions and place new alternatives – particularly if the regime tries to escalate its military operations. This battle also prevented the Syrian regime from displacing the remaining pockets of resistance in the ‘Damascus province’ to Idlib or Jarablous to secure its grip on the capital indefinitely.

The current clashes will place pressure on the Syrian regime being hit at the heart of its security stronghold in Damascus which dispels the idea that Assad can do away with the opposition completely and retake strategic control of the country, a matter which has been discussed since the start of the revolution.

This battle reaffirms the ability and determination of the Free Syrian army to carry out successful military operations from the Capital to the north and south of the country with the purpose of bringing down the regime. Furthermore, it strengthens the idea that a decisive response from the Syrian opposition is always ready even without any international support to topple the regime.

Since the 31st of December, the Russians, speaking on behalf of the Syrian regime, had promised a nationwide ceasefire that would exclude any demographic changes across the country. However the Syrian regime has since continued to carry out deadly military operations such as that in Wadi Barada and the al-Waer neighbourhood in Homs thinking that it will be part of its final blow to the opposition and marking its official victory as it was portrayed in Idlib. And so the Syrian revolutionaries must use the element of surprise and strike Bashar al Assad in the confines of his own home near the presidential palace in Damascus.

The battle of Damascus is happening simultaneously with a renewed campaign to take Hama province which would open a path into government held city of Hama itself. The air base of Hama is of great importance militarily and is the biggest of its kind in northern Syria. It is used as the starting point for the Syrian Air Force to launch air raids on opposition-held territories.

If the Free Syrian Army is successful in its attempt to take the air base in Hama it would be a great victory for the opposition and one that would curb the reach of the Syrian Air force. It should also be mentioned that there is no official incident that has indicated the present entrance of the opposition into the highly populated city of Hama or even the targeting of key points of the metropolitan and its suburban districts.

Currently the Syrian regime has taken back much of the territory it had lost last week, in and around Damascus, but the battles for areas in Damascus province and Hama province are still raging.

A faction of the Free Syrian army dubbed ‘ Jaish al-Azaa ’ has stated in an official announcement that it would protect the Christian population in Hama province and that it would shelter them from any future confrontations or clashes with the regime. Members of the Free Syrian Army that will engage in the battle for Hama have also stated that they will persevere in their struggle to soften the burden on those fighting in Damascus and to strike a decisive victory in Hama itself.

The Free Syrian Army awaits all the factions of the opposition in Damascus province, including Jaish al Islam which is heavily armed and has a strong presence across the Damascus governorate, to join the revolutionary forces to tilt the balance on the ground in the opposition’s favour. A matter which would allow the FSA to take full control of the Syrian capital Damascus.'

'FSA factions managed to expel Daesh from vast swaths of lands which extends more than 20 km in the eastern Qalamon area which the rebels are attempting to link it with the Syrian Badiyah in order to lift the siege on it.

'FSA factions managed to expel Daesh from vast swaths of lands which extends more than 20 km in the eastern Qalamon area which the rebels are attempting to link it with the Syrian Badiyah in order to lift the siege on it.

The gains were the result of two offensives. The first was launched under the banner ‘ Repelling the Transgressors’ in the eastern Qalamon front with the participation of the Assud Al-Sharqiyah, the Abdou Martyr Forces, Jaysh Al-Islam and the Rahman Legion who succeeded in liberating dozens of positions in that area, including the strategic Al-Afai Mountain which was the last main stronghold of Daesh in the eastern Qalamon.

The second was launched with the participation of Assud Sharqiya, Abdou Martyrs Forces and the Qaryatyn Battaion who managed to liberate the Tayss area, the Scientific Research Company, the Makhol Checkpoint, the Abu Risha dam, the Dada Checkpoint, the Saab Bayar area and the Mahassah crossroad on the Abu Shamat highway in the Syrian Badiya.

Saad Al-Diri, member of the Assud Sharqiya media office, told D24 that ‘ The organization have suffered heavy casualties since the start of the offensive. Around 23 of their affiliates were killed and more than 40 others were wounded. The Assud Sharqiya sustained 2 casualties in addition to some injuries. “

He added, “ the Assud Sharqiyah managed to capture an arms depot belonging to Daesh, in addition to 25 Kalashinkov rifles, 5 PKC machine guns and three 14.5 mm anti-aircraft, as well as a tank and 5 four-wheel drive vehicles.”

Clashes are still taking place between the FSA factions and Daesh in the Mahasah area which the rebels are trying to take over in order to lift the siege imposed on the eastern Qalamon, which has been imposed by Daesh and Assad’s forces, and then move deep into the Syrian Badiya, mainly to the Alyaniya and Khuneifiss, which are under the control of the organization.

If the FSA capture the Mahassah area they will cut off the only supply route of the organization in the Beer and Tel Shahab areas, as well as the Safa and Malah hills. It is surrounded by Assad’s forces from two sides, the first of which is the Seen Airport and the second is the Suwaday province, while the remaining areas are controlled by the rebels.

Talass Salama, the general commander of the Assud Sharqiya, confirmed to D24 that’ the battles will continue until we the siege on eastern Qalamon is lifted and expel Daesh from the entire of the Syrian Badiya from which we would advance to Deir Ezzor, which has been under the control of the group for more than three years, and liberate it.’

Despite the fact that the FSA in eastern Qalamon were not backed by any logistic or ground support by the international coalition, they have succeeded so far to liberate hundreds of km from Daesh. The factions operating in that region are relying only on basic weapons and the strong will of their manpower which is the main factor that led to their success against the organization.

Jaysh Assud Sharqiya are among the most effective in the fight against Daesh since they have fought the regime since they faction was formed and were also among the first who fought against the organization in Deir Ezzor until 2014. Then, they moved to the eastern Qalamon which is now their base from which they would advance to Deir Ezzor.

Jaysh Assud Sharqiya, in addition to other factions from Deir Ezzor, are the most popular among the locals in the province. They are the best alternative for Daesh in the province and if the advanced to the province, the liberation of it would be easy because of the strong local support to those factions that would trigger an inner resistance against the organization and, therefore, facilitating the liberation process.

If those factions were overlooked and the liberation of Deir Ezzor was given to both, the SDF and Assad’s forces, It would push many of the locals to join the ranks of Daesh to prevent those parties from entering into their province for ideological and tribal differences.'

Houssam Muhammad Mahmoud:

Houssam Muhammad Mahmoud: '

When Donald Trump issued his first travel order in January, halting the arrival of refugees from everywhere and permanently banning Syrian refugees, I contacted friends from Syria in the United States who I thought might be candidates for deportation.

“Our hearts are with you!” I wrote. “We will pray for you. Don’t panic. Resist until the end and never surrender.” I offered to lobby the news media if one of my friends sent photos and videos to my dropbox. He replied with a sour-faced smiley.

It was my attempt at humor. I live in Madaya, nestled below snowcapped mountains northwest of Damascus. Once a town of 10,000 residents, it swelled to 40,000 during the war. We have been under siege for the past 20 months, blocked from coming or going by the Assad regime and by its ally, Lebanon’s Hezbollah militia. We’re convinced that Iran is directing this.

Madaya came into the news a year ago, when people were dying daily of starvation. After an international furor, Hezbollah and the government allowed UN aid convoys in. They arrive once every three or four months, but we lack all the necessities of life—food, fuel, medicine, milk, detergent, electricity, sewing needles, shoes, slippers. A pack of matches costs the equivalent of $13. A pound of sugar can cost up to $100; of coffee, $50. Except for social media, we’re cut off from the world.

We are often under attack. In December, it was days of machine gun and sniper fire, followed by 600 shells and more than 30 improvised “elephant” rockets. Five people died and 65 were wounded. The latest round of bombing began when the UN convened peace talks in late January; 12 people have died from the elephant rockets since then. The wounded had to be treated in their homes because the hospital was destroyed in the December bombing. Our doctor is a veterinarian.

People are still dying of starvation. Madaya went without milk for 11 months. For a while, Hezbollah members were selling it for $100 a pint, but that, too, has stopped. Children are getting just a fraction of the protein and calcium they need. In November, five infants died at birth because their mothers didn’t have the nourishment needed during pregnancy. What grieves us most is the deaths of relatives and friends that could have been prevented if they had been able to leave for medical care.

Just in the past weeks, Ali Ghuson, 30, died of kidney failure. We had been trying to get him evacuated for medical care for four months. There are 27 other people waiting for such evacuations. A mother died in childbirth with her infant. Two women died of illness, one of kidney failure, another of heart illness. Others have died from sniper shootings and shelling, including a 2-year-old child.

I was born in Madaya in 1987 and was a fourth-year student of French literature at the University of Damascus when the Syrian revolution erupted six years ago. I live with my mother and brother here in Madaya and teach at a junior high and high school. When the Assad regime began attacking the nearby town of Zabadani in July 2015, I became a media activist, using my camera to document the barrel bombings there and in Madaya. I began posting the videos on the Internet.

I am haunted by what I’ve witnessed. I recall trying to extricate the body of a man buried under the rubble—along with his wife, a daughter, and another relative—only to have his limb separate from his body. We stayed three hours into the night to bury them because a sniper was shooting at us.

I have nightmares. I see the bodies of people who died in bombings. I see the people who died of starvation and who I helped to bury. I will always remember Suleiman Fares, a farmer, aged 50, who weighed only 55 pounds when we buried him.

I have had personal trauma. Because I have been a media activist, I cannot stay in the town when the government takes it back or I will be drafted, so I was on the list of 1,500 townspeople scheduled to leave this past December as part of an agreement between the regime and the town leaders. It was a bleak moment; we knew we’d be leaving behind our families and our memories. Despite all the calamities, Madaya is still our home. Some of us roamed the streets taking pictures and saying farewell. Then the deal fell through, so I am still here.

No one thinks the current situation will last for long. We’ve seen the government starve other towns and then deport their residents. We weep as we watch. First, Daraya last August, then Moadamiya in October, then Khan Al Sheih in November, Al Tal and East Aleppo in December, and then in January Wadi Barada. Except for Aleppo, almost no one outside of Syria noticed.

Many of us think the regime has promised Madaya and Zabadani to Hezbollah as a reward for its military support. Madaya lies just over the mountain and across the border from Shiite villages that Hezbollah controls in Lebanon. Hezbollah isn’t leaving the area. Their forces are stationed in regime checkpoints, but they are in charge. They built a big underground base called Marj al Tal in the Madaya valley. Every night, we see Hezbollah trucks carrying weapons and driving through the plain of Zabadani to Lebanon.

A local youth who joined the National Defense Force, a Syrian regime militia, told his family about a quarrel he’d had with a member of Hezbollah about the future of the two towns. “When will the people of Zabadani be back?” the NDF member asked. The Hezbollah fighter responded, “This land belongs to us now. We paid the price in martyrs.” Hezbollah is not here to fight those who revolted against the regime but for its own agenda. Hezbollah wants to build a state that extends from the Bekaa Valley in Lebanon through Zabadani to Qusair in Homs province.

Madaya was once a very rich place. Everyone had a car. Everyone had a second house and land in the mountains. Many townspeople had big investments in Damascus, and many Damascenes had homes here or in Zabadani. But it’s long been known as a “town of troublemakers.” Because it’s just across the border from Lebanon, our markets once were full of smuggled foreign goods.

Our first anti-regime demonstration in the Arab Spring was on March 18, 2011, three days after the protest in Daraa, in the south. We didn’t demand reform; we were in the streets chanting “The people demand the fall of the regime.”

The first year of the revolution was peaceful in Madaya, and then the regime facilitated access to weapons. It was very subtle. Soldiers at checkpoints around the town were allowed to sell us their weapons. On one occasion, the regime attacked the town but on withdrawing left behind a truck full of ammunition.

In January 2012, the people of Madaya and Zabadani announced that the two towns had been liberated. It was a crazy step. We never had the weapons or ammunition, but the will of the people, especially the youth, drove everyone toward folly. People here are very proud, even arrogant.

The siege began in early July 2015 with a government and Hezbollah offensive against Zabadani. The ceasefire two months later, arranged by Iran, paired Madaya and Zabadani, two Sunni mountain towns with a population of more than 60,000, with Fouaa and Kafraya, two mostly Shiite towns under siege from Islamist rebels who’d conquered Idlib province that spring. Iran negotiated the deal for the Syrian regime. From then on, no aid came to Madaya unless the same aid went to Fouaa and Kafraya, with a total population of 10,000.